Introduction:

The rise of e-cigarette use, or vaping, among young people has become a significant public health concern. To better understand and address this issue, we employed machine learning algorithms to predict e-cigarette use among youth in Ontario. This study, leveraging random forest methodologies, provides critical insights into the factors influencing both ever-use and daily use of e-cigarettes. While this research utilizes random forests, the implications extend to the potential of more advanced techniques like Cigs Deep Learning for future studies in tobacco and related substance use prediction. Understanding these patterns is crucial for developing targeted interventions and policies to protect youth from nicotine addiction and potential progression to cigarette smoking.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from the 2019 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS), a representative sample of elementary and high school students in Ontario (N=6471). We defined “ever-vaping” and “daily vaping” based on vaping frequency over the preceding 12 months. A comprehensive set of individual characteristics—176 variables for ever-vaping and 179 for daily vaping—were considered as potential predictors. Utilizing cross-validation techniques, we developed random forest algorithms for both outcomes. Model performance was evaluated using the C-index, a metric for assessing a model’s discriminatory ability. Furthermore, we identified the top 10 predictors based on relative importance scores and investigated their statistical interaction with sociodemographic characteristics. This approach lays the groundwork for future explorations using cigs deep learning methodologies to refine and enhance predictive accuracy.

Results:

Our analysis revealed that 2064 respondents (31.9%) were ever-vapers, and 490 (7.6%) were daily users. The random forest algorithms demonstrated strong predictive capabilities for both outcomes, achieving C-index values exceeding 0.90. Key predictors for daily vaping included caffeine, cannabis, and tobacco use, e-cigarette source and type, and school absenteeism in the preceding 20 days. For ever-vaping, significant predictors encompassed school size, alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco use. Notably, nine of the top 10 predictors for ever-vaping exhibited interactions with ethnicity. These findings underscore the complex interplay of factors influencing youth vaping behaviors, areas where cigs deep learning could offer more nuanced insights in subsequent research.

Conclusion:

Machine learning, particularly random forest algorithms, is a valuable tool for identifying risks associated with both ever-vaping and daily vaping among youth. The methodology allows for the identification of key predictors and the assessment of complex interactions, informing the development of targeted public health policies for specific population subgroups. Looking ahead, the application of cigs deep learning techniques holds promise for even more sophisticated predictive models. Future longitudinal studies can further validate these important predictors and explore the potential of cigs deep learning to personalize public health interventions and prevention strategies related to vaping and, potentially, cigarette smoking in youth.

Keywords: cigs deep learning, machine learning, vaping, smoking, Ontario, youth

Highlights

- This study showcased the effectiveness of machine learning in youth tobacco research by incorporating a wide array of predictors.

- Top predictors for daily vaping included caffeine, cannabis, and tobacco use, e-cigarette source and type, and recent school absence. Ever-vaping predictors featured school size and alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco use.

- Future longitudinal research should validate these key predictors of vaping, potentially guiding policies to prioritize substance use-related strategies.

- Interaction analysis quantified the strength of interactions between significant predictors and sociodemographic factors, warranting further investigation in longitudinal studies, potentially enhanced by cigs deep learning approaches.

Introduction

Research indicates a rapid increase in nicotine vaping prevalence among North American youth aged 16 to 19 between 2017 and 2018.1 Specifically, ever-vaping rates rose from 29.3% to 37.0%, and past 30-day vaping increased from 8.4% to 14.6% among Canadian youth. Alarmingly, youth are increasingly reporting symptoms of vaping dependence, defined as “the constellation of behaviors and symptoms that are distressing to the user and promote the compulsive use of vaping due to nicotine and non-nicotine factors.”2,p.257 A prospective cohort study suggests a potential link between vaping dependence and the persistence and escalation of future tobacco use among US Grade 12 students.3 By 2020, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported approximately 3000 hospitalizations and deaths associated with vaping product use.4 These trends highlight the urgent need for effective predictive models, and the potential for advanced techniques like cigs deep learning to contribute to this area.

Previous studies on vaping dependence, utilizing validated scales such as the PROMIS-E and the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index, have linked increased vaping dependence symptoms to older age, longer use duration, higher vaping frequency, higher nicotine concentrations, and current cigarette smoking.5,6 However, traditional statistical regressions used in these studies have limitations. Reliance on p-values for feature selection might overlook relevant predictors not deemed statistically significant. Furthermore, the complexity of vaping dependence, potentially correlated with numerous characteristics, poses challenges for regression models to fully capture these intricate relationships. This complexity can lead to statistical issues like multicollinearity and overfitting, hindering the comprehensiveness of study findings.

To overcome these limitations, we adopted a machine learning approach in this study. Machine learning—defined as “a group of data-driven analytical methods that rely on computational power to perform statistical tasks”7,p.1317—is gaining traction in health research.8–11 Compared to conventional statistical methods, machine learning offers improved predictive accuracy, given appropriate strategies to mitigate overfitting risks.12 Throughout this paper, we use the machine learning definition of “predictor” to refer to a prediction model, without implying temporal or causal relationships. This methodology focuses on identifying variables most “important” for prediction, measured by their impact on improving the model’s area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC), rather than relying on variance estimates and p-value hypothesis testing. While some studies have applied machine learning methods like classification trees13 and random forests14 in tobacco research, a recent scoping review suggests limited connections to public health impacts.15 The evolution of these methods towards more sophisticated techniques like cigs deep learning could bridge this gap by providing even more actionable insights.

Therefore, our study aimed to further investigate ever-vaping and daily vaping (as a proxy for vaping dependence) among youth, employing machine learning methods to generate interpretable findings. Specifically, our objectives were to develop machine learning algorithms to predict both ever-vaping and daily vaping among Ontario youth, and to conduct post hoc analysis. This analysis included ranking the importance of individual risk factors for both outcomes and illustrating statistical interactions to pinpoint particularly vulnerable youth subgroups. The insights gained from this study, and future research incorporating cigs deep learning, are crucial for informing targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Methods

Data and participants

This study utilized data from the 2019 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS), which included responses from 14,142 students across 992 classes in 263 elementary and secondary schools from 47 Ontario school boards.16 The OSDUHS employed a complex survey sampling design with schools clustered within 26 geographical strata. Four different questionnaire types were used. We included only survey types containing the question, “In the last 12 months, how often did you smoke e-cigarettes?” and excluded students who did not answer this question, resulting in a total of 6471 respondents. The sample for daily vaping analysis was limited to ever-vapers, totaling 2064 respondents.

Measures

Outcome

We created binary outcome variables for daily vaping and ever-vaping using the same survey question. Participants reporting no lifetime e-cigarette use were classified as “never-vapers,” while all others were “ever-vapers.” Participants who vaped at least daily were classified as vaping dependent; others were categorized as not daily vaping.

Potential determinants

We considered 179 and 176 person-level characteristics as potential predictors for daily vaping and ever-vaping, respectively16 (see Appendix at https://osf.io/x36p8/ for a complete variable list). These variables covered administrative information, demographics, school life, family life, physical and mental health, driving behaviors, experiences with intoxicated drivers, vaping behaviors, substance use, perceptions and exposures, sociodemographic characteristics, and other substance use risk behaviors. We excluded variables conditional on either daily vaping or ever-vaping based on survey design (i.e., questions asked only to students who had ever vaped were not used as predictors for ever-vaping). We collapsed levels for several variables to simplify analysis. Numeric variables were scaled using z-score normalization before model building. The richness of this dataset provides an excellent foundation for future studies that could benefit from the pattern recognition capabilities of cigs deep learning to uncover more subtle relationships.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics and imputation of missing values

We summarized respondent demographic characteristics and the prevalence of ever-vaping and daily vaping. Over 90% of variables had less than 5% or between 5% and 10% missing data. A variable describing special education types had 10% missingness. Categorical variables were either collapsed with reference levels or options indicating response uncertainty. Missing values for all numeric variables were imputed using the median.

Random forest algorithm

Using the R version 3.6.3 package “caret,”17 we developed a random forest algorithm—an ensemble machine learning algorithm composed of numerous classification trees—to classify respondents for primary outcomes.18 For daily vaping prediction, each tree classified respondents as either daily vapers or not. The class receiving the majority of votes across all trees became the random forest prediction. This “wisdom of the crowd” approach enhances the random forest’s accuracy and robustness for prediction.19 While random forests are effective, exploring cigs deep learning architectures in future research could potentially yield even more accurate and nuanced predictions.

Development and validation of random forests for daily vaping and ever-vaping

We included all candidate predictors to train the models, excluding outcome-conditional variables. We randomly split the dataset into training (70%) and test (30%) sets for daily vaping (n=1612 and 691) and ever-vaping (n=4680 and 2006) classification. Both ever-vaping and daily vaping outcomes were imbalanced. To improve model training efficiency, we applied the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to balance training data for both outcomes.20 During 10-fold cross-validation in model training, the dataset was randomly divided into 10 equal subsamples. In each iteration, nine subsamples trained the model, and the remaining subsample validated it. This was repeated 10 times. We evaluated model performance using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC for daily vaping and ever-vaping classification on the test set. The average performance across 10 iterations represented the model’s overall performance. AUC exceeding 0.80 indicated good discriminatory ability, a standard threshold for classification models.21 Future studies could compare the performance of these random forest models against cigs deep learning models to assess potential improvements in predictive power.

Ranking individual risk factors for daily vaping and ever-vaping

To identify the top 10 predictors for daily vaping and ever-vaping, we ranked all predictors by scaled relative importance scores (0–100). This score is calculated from the total accuracy loss due to excluding a predictor for each tree, divided by the total number of trees.22,23 One-way partial dependence plots for the top 10 predictors visualized their marginal effects on predicted risks of daily and ever-vaping, holding other predictors constant.24 A partial dependence plot for a single predictor illustrates outcome probabilities across different values of that predictor. Higher probabilities indicate greater outcome risk under the influence of that predictor. We also applied these methods to sociodemographic characteristics. This feature importance ranking is a crucial step that could inform the design of cigs deep learning models, focusing on the most influential variables.

Exploration of interactions

We examined two-way interactions between the top 10 predictors and sociodemographic predictors known to robustly predict smoking-related outcome inequities.25 We also explored interaction effects among the following sociodemographic pairs: age and sex, age and ethnicity, age and socioeconomic status (SES), sex and ethnicity, sex and SES, and ethnicity and SES, using a simple feature importance ranking approach.26 SES was subjectively rated by respondents on a ladder from zero to 10.27 Two-way partial dependence plots illustrated daily and ever-vaping risks for pairs with interaction strengths exceeding 0.1. Partial dependence probabilities were calculated based on the variation of the two predictors, while keeping others constant.28 Analyzing these interactions is vital for developing targeted interventions, and cigs deep learning models could be trained to specifically capture and leverage these complex interaction effects.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted two sensitivity analyses using the same oversampled training set for both outcomes. First, we fitted random forest algorithms using only the top 10 identified predictors. Second, we constructed base multivariate logistic regression models including age, sex, ethnicity, and SES. We evaluated the performance of these logistic models using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC on the test set and compared them to the random forest measures from the primary analysis. This comparison provides a benchmark and highlights the potential advantages of more advanced machine learning techniques, including cigs deep learning, over traditional regression models.

Results

Sample characteristics

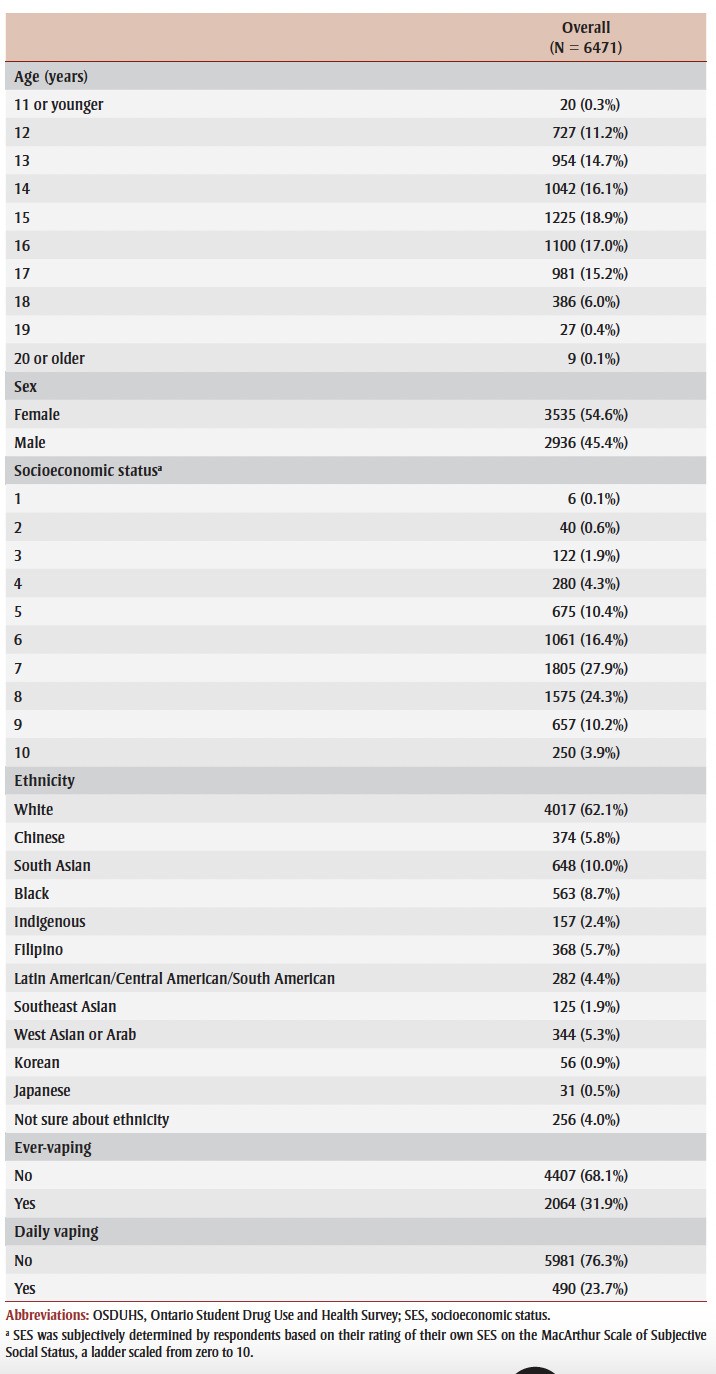

The 6471 respondents were categorized into 10 age groups (0 to 11, individual years between 12 and 19, and 20+ years); 54.6% were female; the majority (68.6%) reported family SES in the 6-8 range on the ladder; and 62.1% identified as White (Table 1). There were 2064 ever-vapers (31.9%) and 490 daily vapers (7.6% of the total sample, or 23.7% of ever-vapers).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample eligible respondents to OSDUHS 2019.

Performance of the random forest algorithms

Both random forest algorithms achieved high performance. The ever-vaping algorithm had a testing accuracy of 0.82 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.81–0.84), sensitivity of 0.83 (0.80–0.86), specificity of 0.82 (0.80–0.84), and AUC of 0.90. The daily vaping algorithm showed a testing accuracy of 0.83 (0.80–0.86), sensitivity of 0.85 (0.77–0.90), specificity of 0.82 (0.78–0.86), and AUC of 0.90. These strong performance metrics suggest that machine learning, including the potential of cigs deep learning, offers a robust approach to predicting youth vaping behaviors.

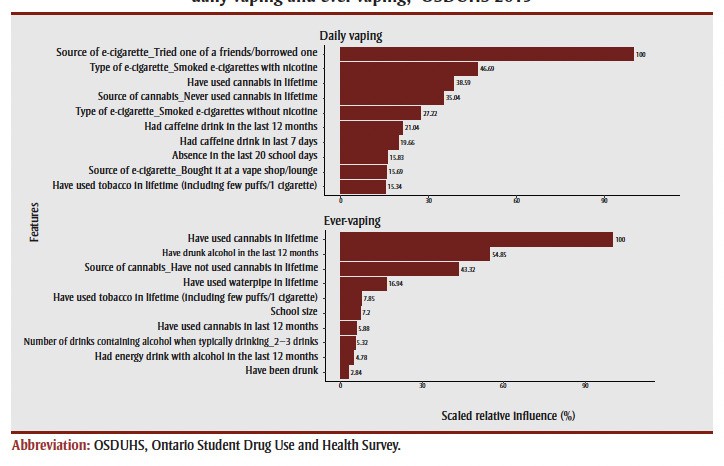

Top 10 predictors of ever-vaping and daily vaping

The algorithms identified distinct top 10 predictors for daily vaping and ever-vaping (Figure 1). The top 10 predictors for ever-vaping were: lifetime cannabis use; past 12-month alcohol consumption; cannabis source; lifetime waterpipe use; lifetime tobacco use; school size; past 12-month cannabis use; typical alcohol drink quantity; past 12-month energy drink with alcohol; and having been drunk. For daily vaping, the top 10 predictors were: e-cigarette source/friend’s e-cigarette; nicotine e-cigarette use; lifetime cannabis use; cannabis source; non-nicotine e-cigarette use; past 12-month caffeine drink; past 7-day caffeine drink; school absence in last 20 days; e-cigarette source/vape shop purchase; and lifetime tobacco use. Sociodemographic predictors showed minimal influence for both outcomes, with relative importance scores below three, thus their partial dependence plots were not reported. This highlights the importance of substance use behaviors and access factors over traditional demographic variables in predicting vaping, an area where cigs deep learning could further refine predictor identification.

Figure 1. Scaled relative importance plots of the top 10 correlates of daily vaping and ever-vaping, OSDUHS 2019.

Partial dependence on the top 10 predictors

Partial dependence plots for ever-vaping indicated higher ever-vaping risks among respondents who had used cannabis in the past 12 months or lifetime, consumed alcohol with or without high-energy drinks in the past 12 months, used tobacco or waterpipe in their lifetime, and had been drunk, compared to those who had not (see Appendix at https://osf.io/x36p8/). Across cannabis sources, past cannabis users showed higher ever-vaping risk than never-users. Respondents typically consuming two to three alcoholic drinks had approximately 25% higher ever-vaping risk than other alcohol users and non-users. Ever-vaping risk increased with school size up to 500 students, remained high until approximately 1850 students, with a slight risk decline for schools with 1850–2000 students.

For daily vaping, increased risk was associated with lifetime cannabis or tobacco use, or past 12-month or 7-day caffeine drink consumption, compared to non-users (see Appendix at https://osf.io/x36p8). Across e-cigarette sources, borrowing from a friend was associated with the lowest daily vaping risk, contrasting with retail purchases. Nicotine-containing e-cigarette use was linked to the highest daily vaping risk. Non-nicotine e-cigarette users had a 25% lower daily vaping risk. Never-cannabis users showed slightly lower daily vaping risk than cannabis users across various sources. Any school absence in the last 20 days was linked to increased daily vaping risk, although causality cannot be inferred from this model. These partial dependence insights are crucial for informing targeted interventions and could be further refined with the complex modeling capabilities of cigs deep learning.

Interactions

All top 10 ever-vaping predictors, except being drunk, showed interactions with ethnicity (see Appendix at https://osf.io/x36p8/). Lifetime tobacco or cannabis use and past-year alcohol consumption interacted with ethnicity, SES, and age. Japanese ethnicity was associated with higher ever-vaping probability across all school sizes, while Southeast Asian and Korean ethnicities showed inverse relationships. Across all cannabis sources, non-Japanese ethnicity was linked to lower ever-vaping probabilities compared to Japanese ethnicity. Regardless of ethnicity, consuming two to three drinks typically had the highest ever-vaping probability. While Japanese ethnicity positively correlated with ever-vaping probability, Southeast Asian or Korean ethnicities were inversely associated. Probability differences between Japanese and non-Japanese ethnicities were smaller for past cannabis or alcohol use, and alcohol combined with energy drinks. This pattern was also observed for lifetime tobacco or cannabis use. Across all SES groups, Southeast Asian or Korean ethnicity was associated with slightly lower ever-vaping probability compared to non-Southeast Asian or non-Korean ethnicities.

Age interacted with past-year alcohol use, lifetime tobacco use, and lifetime cannabis use; substance use was a more potent predictor among younger students than older ones. Similarly, these variables were stronger predictors among higher SES students compared to lower SES students.

Weak interaction was found between caffeine consumption and ethnicity for daily vaping (see Appendix at https://osf.io/x36p8/). The interaction strength between past 7-day caffeine consumption and uncertain ethnicity was 0.111. Past 7-day caffeine consumption was associated with slightly higher daily vaping probability, regardless of ethnicity uncertainty. These interaction findings underscore the need for nuanced, targeted interventions, an area where cigs deep learning models, capable of capturing high-order interactions, could be particularly valuable.

Sensitivity analysis

Consistent with primary analysis results, parsimonious random forest algorithms using only the top 10 predictors showed high performance. The parsimonious daily vaping model had an accuracy of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.78–0.84), sensitivity of 0.80 (0.72–0.86), specificity of 0.82 (0.78–0.85), and AUC of 0.87. The parsimonious ever-vaping model had an accuracy of 0.78 (0.76–0.79), sensitivity of 0.78 (0.74–0.81), specificity of 0.78 (0.75–0.80), and AUC of 0.86. In contrast, base logistic regressions for both outcomes performed worse than the primary random forest models. Specifically, the daily vaping logit model had an accuracy of 0.53 (0.49–0.57), sensitivity of 0.63 (0.54–0.71), specificity of 0.50 (0.45–0.54), and AUC of 0.60. The ever-vaping logit model had an accuracy of 0.61 (0.59–0.64), sensitivity of 0.82 (0.79–0.85), specificity of 0.52 (0.49–0.55), and AUC of 0.73. This performance difference highlights the advantages of machine learning approaches like random forests, and the potential for even greater gains with cigs deep learning, over traditional statistical methods in predicting complex health behaviors.

Discussion

We applied a machine learning approach to investigate correlates of daily vaping and ever-vaping using OSDUHS data from a representative sample of Ontario youth in elementary and secondary schools. The final random forest algorithms demonstrated high performance. The top 10 predictors differed for daily vaping and ever-vaping, consistent with varying predictors for cigarette initiation and escalation in tobacco research.29–31 While we found no interactions among predictor pairs for daily vaping, we observed interactions between ever-vaping predictors, particularly with ethnicity.

Our study indicates that key predictors for ever-vaping and daily vaping are distinct. While prior research suggested social influences as primary ever-vaping predictors,32 our findings emphasize the importance of cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco use. These results align with the emerging trend of cannabis vaping,33 and the prevalence of nicotine as the primary substance in vaping devices.34 We also identified school size as a significant sociodemographic predictor for ever-vaping risk.

Across e-cigarette sources, the lowest daily vaping risk was among those who tried e-cigarettes from friends, suggesting limited social influence in daily vaping development. Nicotine e-cigarette use was associated with the highest daily vaping risk, unsurprising given nicotine’s addictive nature.35 Our results suggest caffeine, cannabis, and tobacco as important substances increasing daily vaping risk. While literature points to school grade and age as strong drug use sociodemographic predictors,36 our study indicates that increased school absence in the last 20 days may be a more significant contributor to daily vaping risk. These nuanced findings pave the way for future research to explore the potential of cigs deep learning to uncover even more granular and actionable insights.

Strengths and limitations

Methodologically, our study further validates machine learning’s utility in predictive modeling for tobacco control.37 The high performance of random forests provides interpretable findings, such as identifying important features, potentially valuable for policymakers. Given the association between adolescent e-cigarette use and increased odds of cigarette smoking,38 identified features can highlight crucial predictors, potentially preventing youth progression to cigarette use. School absence and school size, less common in literature, emerged as important outcome predictors due to machine learning methods.

Furthermore, the high performance aligns with research demonstrating machine learning’s potential to outperform conventional statistical modeling. For instance, systematic reviews report machine learning models outperforming logistic regression in neurosurgical outcome predictions.39 Similarly, machine learning models show higher C-indexes than clinical risk scores in prognostic performance for acute gastrointestinal bleeding patients.40 The success of these methods, and the promising horizon of cigs deep learning, underscore the paradigm shift towards data-driven approaches in public health research.

Regarding limitations, the cross-sectional design limits us to identifying correlates, not true predictors, of daily and ever-vaping. Despite random forest robustness,41 predictor relative importance does not imply causality, and hypothesis testing was not conducted. Future longitudinal studies with causal designs are needed to address this. More research is also needed to validate interaction findings, given relatively small sample sizes for reported ethnic groups (n<150). While our models performed well with simple missing data imputation, future research could consider more sophisticated methods like multiple imputation if predictor precision is paramount.42

Current random forest algorithm tools cannot incorporate cluster sampling. However, this limitation primarily affects predictor variance, not the study’s focus. Finally, survey studies inherently have limitations like recall and response bias. Nevertheless, we expect robust results due to the OSDUHS survey’s design to optimize response quality. Future research could explore how cigs deep learning models might mitigate some of these biases through advanced data preprocessing and noise reduction techniques.

Conclusion

By training and testing random forest algorithms, we identified distinct sets of top 10 predictors for daily vaping and ever-vaping in a Canadian youth population. We found interactions between important predictors and sociodemographic characteristics for ever-vaping. Identifying predictors for daily and ever-vaping for targeted interventions can inform future longitudinal studies to improve policies designed for subpopulations, irrespective of causality. The promising performance of machine learning in this study, and the future potential of cigs deep learning, highlight a significant advancement in our ability to understand and address youth vaping and related substance use behaviors.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, funding reference number MS2-17073.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

JS, HH and MC conceptualized the manuscript. JS led the writing, statistical analysis and data interpretation, with the guidance of RF and MC. All authors provided feedback, edited drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

[1] Hammond D, Reid JL, Rynard VL, et al. Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: repeat cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2019;365:l2219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2219

[2] Primack BA, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. Vaping and respiratory symptoms in adolescents: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5):e20193227. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3227

[3] Miech R, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. E-cigarette vaping and subsequent cigarette smoking among US adolescents: a prospective cohort study. Tob Control. 2017;26(5):573–580. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053429

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Accessed 10 May 2021.

[5] Moon S, Jackson JS, Roh S, et al. Associations between e-cigarette dependence, cessation attempts, and future cigarette smoking among youth. Addict Behav. 2021;115:106766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106766

[6] Johnson EO, Cullen J, Salloum RG, et al. Measuring dependence on electronic cigarettes: initial validation of the penn state electronic cigarette dependence index (PSECDI). Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):1906–1913. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw142

[7] Obermeyer Z, Emanuel EJ. Predicting and improving the performance of health care systems. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1317–1318. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.2140

[8] Dean J, Ghemawat S, van den Driessche G, et al. Large scale distributed deep networks. In: Proceedings of the 25th international conference on neural information processing systems. 2012. pp. 1223–1231.

[9] Mamoshina P, Vieira A, Putin E, et al. Applications of deep learning in biomedicine. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(5):1445–1454. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00782

[10] Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056

[11] Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

[12] Christodoulou E, Ma J, Collins GS, et al. A systematic review shows no performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;110:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.02.005

[13] Chaiton M, Kundu A, Rueda S, et al. Predicting smoking cessation using classification tree analysis: results from a longitudinal survey of smokers in Ontario, Canada. Addict Behav. 2011;36(12):1252–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.006

[14] Alvarez-Bueno C, Casanova R, Moreno-Murcia JA, et al. Machine learning algorithms for predicting and classifying smoking behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186847

[15] Rueda S, Pinto AD, Nelson M, et al. Machine learning for substance use research: a scoping review of applications, limitations, and future directions. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28(4):e1808. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1808

[16] Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Ontario student drug use and health survey (OSDUHS). 2019. http://www.osduhs.ca/index.cfm?page=home. Accessed 10 May 2021.

[17] Kuhn M. Caret package. J Stat Softw. 2008;28(5):1–26.

[18] Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32.

[19] Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2009.

[20] Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, et al. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–357.

[21] Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013.

[22] Menze BH, Kelm BM, Masuch R, et al. A comparative study of random forest feature importance measures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-1

[23] Strobl C, Boulesteix AL, Kneib T, et al. Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-307

[24] Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001;29(5):1189–1232.

[25] Jackson JS, Ohannessian CM, Park E, et al. Smoking inequities among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2020;29(e1):e1–e11.

[26] Hooker G, Mentch L. Interaction trees. J Mach Learn Res. 2019;20(100):1–31.

[27] Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the socioeconomic spectrum: why did they occur? What can we do? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05124.x

[28] Goldstein A, Kapelner A, Bleich J, et al. Peeking inside the black box: visualizing statistical learning with plots of conditional expected outcomes. Am Stat. 2015;69(1):25–49.

[29] Mayhew ER, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59(Suppl 1):S61–S74.

[30] Escobedo LG, Reddy M, Giovino GA. Predictors of cigarette smoking in US adolescents. Prev Med. 1998;27(2 Pt 1):200–207.

[31] Choi WS, Okuyemi KS, позаботьтесь об этом Froelicher ES, et al. Predictors of smoking initiation and progression among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1170–1176.

[32] Cho JH, Shin SH, Barnett TE, et al. Social influences on adolescent e-cigarette use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019;126:105769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105769

[33] Goodwin RD, Stirling DL, Shiffman S, et al. Prevalence of cannabis vaping among US adults: 2017–2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215:108228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108228

[34] Soule EK, Lipsky MS. Electronic cigarettes: what clinicians need to know. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(3):180–186. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2019.029

[35] Benowitz NL, Fraiman JB. Cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(8):447–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2017.36

[36] Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use 1975–2019: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2020.

[37] Yang Y, Xiao T, Liu L, et al. Machine learning for tobacco control: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(12):2039–2052.

[38] Soneji SS, Barrington-Trimis JL, Sargent JD, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–797.

[39] Khan M, Raja R, Hussain A, et al. Machine learning in neurosurgery: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2021;148:342–355.

[40] Limsrivilai J, Wijarnpreecha P, Panjawatanan P, et al. Machine learning algorithms outperform clinical risk scores in predicting adverse outcomes of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242157.

[41] Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, et al. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Stat. 2008;2(3):841–860.

[42] Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002.