“Begin with the end in mind.” – Stephen Covey

This powerful principle is fundamental to effective teaching. Just as any journey requires a destination, successful learning experiences are built upon a clear understanding of where we want our students to arrive. This “end” in education is defined by Learning Objectives. Rooted in the backward design framework championed by Wiggins and McTighe (2005), defining these objectives is the crucial first step in designing impactful courses and lessons. While many instructors intuitively consider the skills and knowledge they wish to impart, a more structured approach involves articulating these aspirations as specific and measurable learning objectives. This clarity not only guides instructors but also empowers students by providing them with a roadmap of expectations and assessment criteria.

Learning objectives, often used interchangeably with the term “learning outcomes” (Melton, 1997), are precise statements that articulate what students are expected to achieve upon completing a course, module, or lesson. They move beyond broad learning goals, offering concrete benchmarks against which instructors can gauge student progress and success. Consider this illustration of the relationship between a learning goal and a learning objective:

- Learning Goal: “Students will grasp the concept of the scientific method.”

- Learning Objective: “Students will be able to describe the steps of the scientific method and illustrate its application with relevant examples.”

Revised Bloom

Revised Bloom

The Multifaceted Benefits of Learning Objectives

Well-crafted learning objectives are invaluable tools, offering significant advantages for both educators and learners:

For Instructors: A Guiding Compass: Learning objectives serve as a compass, directing the entire course design process. They provide a clear framework for:

- Designing Fair Assessments: Objectives ensure that assessments directly measure the intended learning outcomes, promoting fairness and validity.

- Selecting Relevant Content and Activities: By focusing on objectives, instructors can curate content, activities, and teaching methodologies that are purposefully aligned with student learning needs.

- Integrating Technology Effectively: Learning objectives guide the strategic incorporation of technology to enhance learning and support specific outcomes.

- Ensuring Alignment: They guarantee that all critical course components – assessments, content, activities, and teaching strategies – work synergistically to facilitate student learning and achieve desired goals.

For Students: A Clear Roadmap to Success: Learning objectives act as a map for students, providing transparency and direction. They enable students to:

- Understand Course Expectations: Students gain a clear understanding of what is expected of them to succeed in the course, reducing ambiguity and anxiety.

- Take Ownership of Learning: By knowing the destination, students can proactively direct and monitor their learning journey throughout a lesson, unit, or semester.

- Focus their Efforts: Objectives help students prioritize their study efforts, concentrating on the most critical aspects of the course material.

- Self-Assess Progress: Students can continuously refer back to the learning objectives to self-assess their understanding and identify areas needing further attention.

Defining Effective Learning Objectives: The SMART Framework

To maximize their impact, learning objectives should be meticulously written, adhering to the SMART criteria. SMART objectives are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Result-oriented, and Time-bound. This framework ensures clarity, focus, and effectiveness.

-

Specific: Effective learning objectives are laser-focused. They break down broad topics into manageable components and clearly define the desired outcomes for each. Vague objectives lack direction. Instead of saying “students will understand physics,” a specific objective might be “students will be able to explain Newton’s three laws of motion.”

-

Measurable: As benchmarks for evaluation, learning objectives must be measurable. While learning often involves internal cognitive shifts like perspective changes and knowledge acquisition, these internal processes are not directly observable. Instructors must rely on external indicators – what students say or do – to assess progress. Therefore, objectives should utilize action verbs that describe observable behaviors. Avoid verbs like “understand,” “know,” or “feel,” and instead use verbs such as “describe,” “analyze,” “solve,” or “compare.”

-

Achievable: Objectives must be realistic and attainable within the given context. Consider the resources available, the course timeframe, students’ prior knowledge, and their readiness to learn. The cognitive complexity of the objectives should be appropriate for the course level (e.g., introductory vs. advanced). Setting overly ambitious or unrealistic objectives can lead to student frustration and disengagement.

-

Result-oriented: Objectives should emphasize the outcomes of learning, not just the process or activities. Focus on the knowledge, skills, or attitudes students should acquire as a result of instruction, rather than simply listing tasks they will complete, like “writing a paper” or “taking an exam.” A result-oriented objective focuses on what students will demonstrate after completing these tasks.

-

Time-bound: While not always applicable, incorporating a timeframe can add further clarity, especially for modular or unit-based objectives. Specifying a timeframe helps define the expected level of competency within a given period. For example, “By the end of this module, students will be able to…”

Example of a SMART Learning Objective Breakdown:

Consider the objective: “Students will be able to describe the scientific methods and provide examples of its application.”

- Specific: Focuses on “scientific methods.”

- Measurable: Uses action verbs “describe” and “provide examples,” which are observable and measurable indicators.

- Achievable: Appropriate for an introductory level course.

- Result-oriented: Focuses on the result (describing and providing examples) rather than the learning process itself.

- Time-bound: Implied timeframe – students are expected to master this skill by the end of a unit or module.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Effective Learning Objectives

Creating well-constructed learning objectives involves a systematic approach. Think about the evidence students will provide to demonstrate mastery. A robust learning objective typically comprises two key components: a clear action verb specifying the type of learning and the object of that learning.

Follow these steps to craft compelling learning objectives:

Step 1: Pinpoint the Object of Learning

Begin by identifying the core knowledge, skills, attitudes, or abilities students are expected to gain. What is the fundamental “thing” they should learn?

- Example 1 (Physics): Fundamental principles of physics.

- Example 2 (History): How to analyze primary source material.

Step 2: Determine the Mastery Level Using Action Verbs

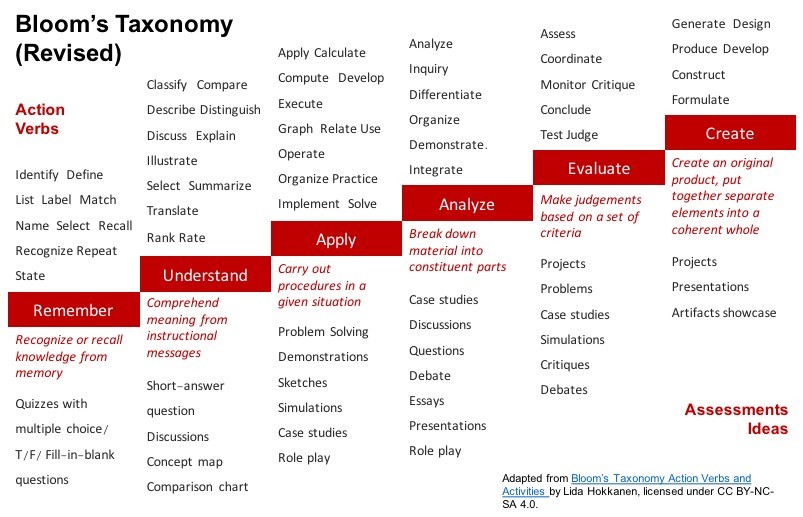

Selecting the right action verb is crucial. Bloom’s Taxonomy, particularly the revised version (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), provides a valuable framework for choosing verbs that align with different levels of cognitive complexity. Bloom’s Taxonomy categorizes cognitive processes from lower-order thinking skills (remembering, understanding) to higher-order skills (analyzing, evaluating, creating).

- Example 1 (Physics): For fundamental principles of physics, the action verb could be “apply” (moving beyond just understanding to practical application).

- Example 2 (History): For primary source material analysis, a higher-order verb like “critique” might be appropriate, signifying a deeper level of engagement.

Refer to Bloom’s Taxonomy verb list (like the image provided) to select verbs that accurately reflect the desired level of cognitive engagement for each objective.

Step 3: Construct the Complete Learning Objective Statement

Combine the object of learning (Step 1) and the action verb (Step 2) to create a concise learning objective statement.

- Example 1 (Physics): “Students will be able to apply fundamental principles of physics to real-world situations.”

- Example 2 (History): “Students will be able to critique primary source material from the 18th and 19th centuries.”

Step 4: Refine and Enhance Your Objectives

The initial draft can often be improved. Use a checklist, such as the Learning Outcome Review Checklist from Cornell University, to evaluate and refine your objectives. Consider adding context, specifying the format of demonstration, or adding depth to the objective.

- Example 1 (Physics – Refined): “Students will be able to apply fundamental principles of physics to real-world situations in both speech and writing.” (Adds communication modalities)

- Example 2 (History – Refined): “Students will be able to critique primary source material from the 18th and 19th centuries, including such considerations as authenticity, reliability, and bias.” (Adds specific criteria for critique)

Implementing Learning Objectives: Alignment is Key

Even the most meticulously crafted learning objectives are ineffective if they are not directly connected to the course’s instructional content, activities, and assessments. Misalignment undermines the entire learning process. If assessments and content don’t align with objectives, instructors lack the data to gauge student success, and students become confused and disengaged. The action verbs within objectives are particularly useful for ensuring alignment across all course components.

Illustrating Alignment:

Example of Misaligned Objectives and Assessments:

- Learning Objective: “Students will be able to compare and contrast the benefits of qualitative and quantitative research methods.”

- Assessment: “Write a 500-word essay describing the features of qualitative and quantitative research methods.”

In this scenario, the assessment only requires description, not the comparative analysis implied by the objective.

Example of Well-Aligned Objectives and Assessments:

- Learning Objective: “Students will be able to analyze features and limitations of various sampling procedures and research methodologies.”

- Assessment: “Comparison chart assignment” (requiring students to analyze and compare features and limitations in a structured format).

The second example demonstrates strong alignment, where the assessment directly requires students to use the analysis skills stated in the learning objective.

Conclusion

Learning objectives are the cornerstone of effective instructional design. By starting with the end in mind and clearly defining what students should achieve, educators can create focused, engaging, and impactful learning experiences. Investing time in crafting SMART, well-aligned learning objectives is an investment in student success and a more purposeful and effective teaching practice.

References

- Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

- Melton, R. (1997). Objectives, Competencies and Learning Outcomes: Developing Instructional Materials in Open and Distance Learning. London, UK: Kogan Page.

- Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.