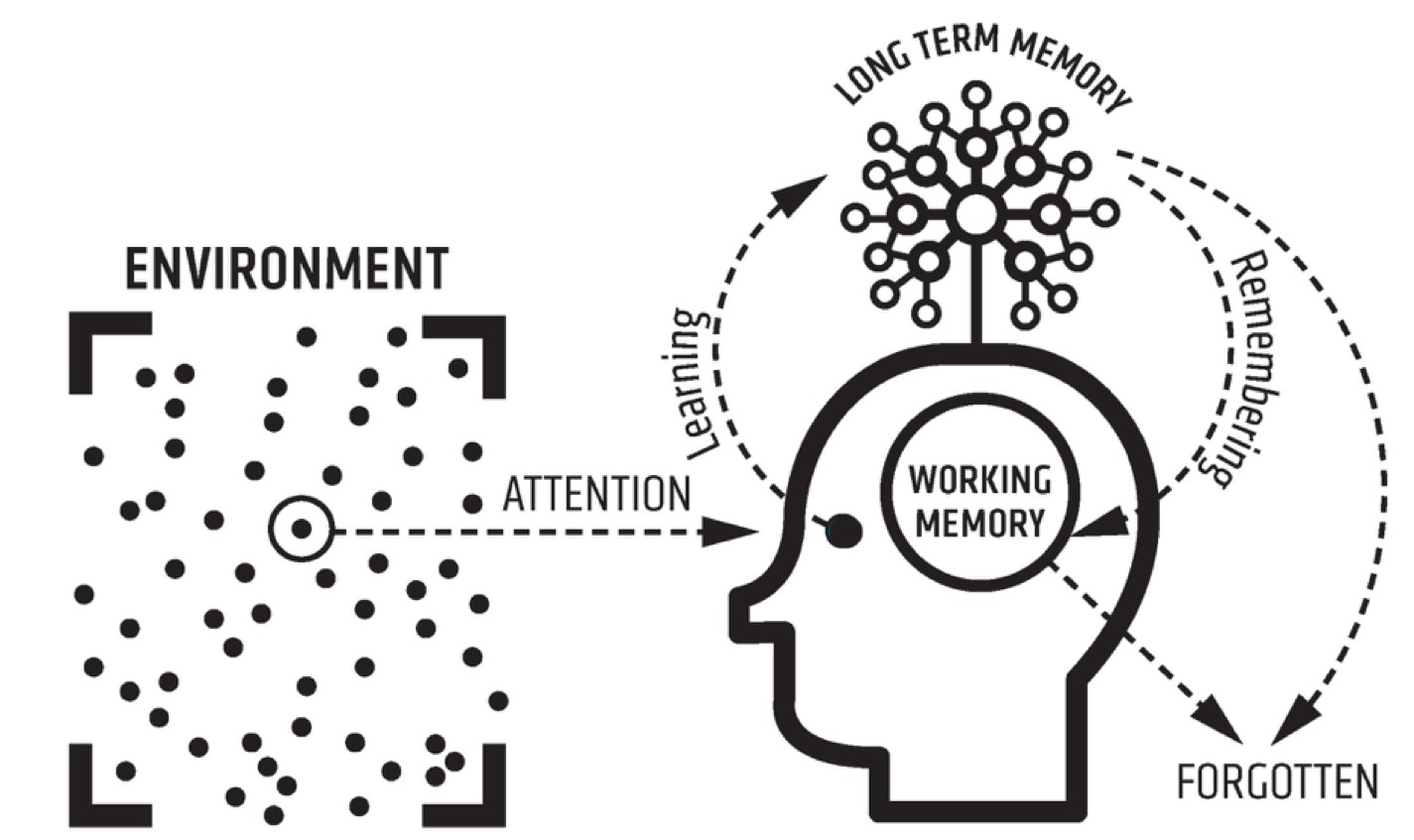

One of the most insightful concepts I’ve encountered recently is visualizing the Learning Process through a diagram. This model helps to understand how learning generally occurs and pinpoint why it sometimes fails. The diagram below, from my Rosenshine Principles book courtesy of Oliver Caviglioli, effectively illustrates this:

I’ve found this diagram incredibly useful during professional development sessions as a focal point for exploring interconnected ideas.

The almost inevitable nature of forgetting, the crucial role of retrieval practice, the necessity of linking new information to existing knowledge, and numerous other related topics can be thoroughly discussed when we have a shared framework like this diagram.

(Note: The colored labels represent potential discussion points around the diagram and are not intended to overcomplicate the basic model. I would advise introducing these labels only after an initial discussion in a CPD context.)

It’s frustrating when people dismiss simplified models as simplistic thinking. Schema-building, as I’ve discussed before, is a rich and complex process. “Remembering” and “learning” are broad terms encompassing almost everything we learn. They are expansive, not reductive. Similarly, simply stating “it’s more complicated than that” is unhelpful and avoids proposing alternative explanations.

If someone suggests, perhaps dismissively, that education has been reduced to “memorizing knowledge,” it’s worth discussing. Reframing knowledge and memory as broad terms, we can see that building schemas (composed of knowledge, beliefs, memories, preferences, etc.) in our memory (hence, memorized?) is a sufficiently robust concept to address many educational goals. If someone disagrees, they should offer a better model, not just dismiss this one. This allows for constructive debate between competing models rather than vague objections like “there’s more to it.”

In teacher CPD, the primary value of such a model is its explanatory power and its ability to suggest solutions to common problems. In my experience, the diagram above consistently achieves this. For instance, students fail to learn for various reasons, and this model helps understand why:

Attention Deficits: Students may not absorb information during lessons because their attention is not focused on the key learning points. It could be elsewhere. Simply being in the same room during a discussion doesn’t guarantee learning. Solution: Implement strategies to secure attention, use narrative structures, employ inclusive questioning techniques, and utilize attention-grabbing stimuli.

Memory Overload: Working memory has limited capacity. Students are often bombarded with too many ideas and pieces of information, overwhelming their processing abilities, hindering comprehension and retention. Solution: Break down complex concepts and tasks into smaller, manageable steps and elements.

Lack of Prior Knowledge: A significant, often unseen variable is students’ existing knowledge. They may lack the necessary schema for the concepts being taught, making it difficult to understand and retain new information. Solution: Develop a comprehensive curriculum rich in knowledge and experiences across various interconnected domains to help students fill knowledge gaps and expand their schemas. Routinely assess students’ prior knowledge as part of teaching, rather than making assumptions.

Insufficient Fluency of Recall: Often, learning difficulties stem from a lack of practice. Students may not have had enough opportunities to practice retrieving and applying their knowledge with sufficient frequency, intensity, or variety to develop the fluency and confidence required to progress. Solution: Increase the range, intensity, and frequency of practice tasks to build student confidence and fluency.

Task Completion as a Poor Proxy for Learning: Students can complete tasks immediately after instruction or by simply accessing presented information without truly embedding it in long-term memory or developing recall fluency for later use. Solution: Implement more frequent checks for understanding and encourage generative activities with gradually removed support. Space practice to strengthen long-term memory and recall, moving away from the illusion of knowing based on recent exposure.

These are just a few examples of the issues this model addresses. It provides a framework for understanding common classroom challenges and offers practical solutions.

This model is relevant to subject-specific learning—math, writing, history, art, science, etc. There’s also a layer concerning social and emotional development and thinking patterns. A more complex model could potentially integrate these aspects, showing them as separate yet interacting elements to further clarify our understanding. Motivation, responses to feedback, self-image, and sense of purpose could also be included. However, forcing everything into a deliberately simple schema-building cycle risks making the model too cumbersome and losing its simplicity.

The aim isn’t to create a universal model for everything, burdened by excessive complexity. Instead, the goal is to develop useful, versatile models that offer insights and solutions within defined boundaries to maintain their validity and practicality.

Personally, since incorporating this schema-building model into my work, I’ve found it incredibly powerful. Given the numerous areas of teaching and learning it impacts and the significant potential for improvement within those areas, I anticipate relying on this model for the foreseeable future.