Abstract

Background: The benefits of physical activity for maintaining a healthy weight and reducing the risk of chronic diseases are well-established. However, a significant portion of both adults and children worldwide fail to meet recommended physical activity levels. Traditional interventions often prove ineffective in engaging inactive populations. Interestingly, anecdotal evidence suggests that novel mobile games, which integrate gameplay into the physical world, can promote increased physical activity. Pokémon Go, a prominent example, has garnered millions of users globally.

Objective: This study aimed to rigorously assess the impact of Pokémon Go on physical activity levels.

Methods: We analyzed data from a large dataset of 32,000 Microsoft Band users over three months, combining wearable sensor data and search engine logs. Pokémon Go players were identified through their search queries, and physical activity was measured using accelerometer data.

Results: Our findings indicate that Pokémon Go significantly boosts physical activity over a 30-day period. Highly engaged users, defined as those with multiple search queries related to game usage, increased their daily steps by an average of 1473 steps – a more than 25% increase compared to their baseline activity (P<.001). We estimate that Pokémon Go contributed an additional 144 billion steps to overall physical activity in the US within the study timeframe. Notably, the game’s positive impact extended across demographics, including men and women of all ages, weight statuses, and prior activity levels. Crucially, Pokémon Go effectively reached previously low-activity populations, a stark contrast to the four leading mobile health apps we examined, which primarily attracted already active users.

Conclusions: Mobile applications that merge gameplay with physical activity demonstrate substantial short-term increases in activity levels. Unlike many conventional interventions and mobile health apps, these games possess the potential to engage populations with low levels of physical activity, offering a novel avenue for Activity Learn and public health initiatives. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects of such applications and their sustained impact on activity learn and behavior change.

Keywords

physical activity; Pokémon Go; mobile health; mHealth; wearable devices; mobile applications; games; exergames; public health; activity learn

Introduction

“Those who think they have no time for bodily exercise will sooner or later have to find time for illness.” – Edward Stanley, Earl of Derby, December 20, 1873

Physical activity is fundamental to human well-being. Active individuals tend to enjoy longer lifespans and face reduced risks of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, depression, and certain cancers. They are also more likely to maintain a healthy weight [1,2,3,4]. Global analyses attribute 5.3 million deaths annually to physical inactivity [5], resulting in a staggering US$67.5 billion in global economic burden due to healthcare costs and lost productivity [6]. Alarmingly, only 21% of US adults meet the recommended physical activity guidelines (at least 150 minutes weekly), and less than 30% of US high school students achieve the recommended 60 minutes of daily physical activity [7,8]. Promoting physical activity represents a significant opportunity to enhance public health, prompting calls for widespread, population-based strategies [9,10]. However, many interventions have proven ineffective [11,12], often reaching only those already active [13,14] or lacking scalability across diverse cultural, geographic, social, and economic landscapes [9].

Recently, there have been anecdotal accounts of mobile games driving increased physical activity, most notably Pokémon Go [15], alongside games like Ingress and Zombies, Run!. Pokémon Go ingeniously blends the Pokémon universe with augmented reality in the real world, compelling players to physically move to engage with the game. Released in the US on July 6, 2016, Pokémon Go quickly achieved widespread adoption globally, boasting 25 million active US users [16], 40 million worldwide [17], and 500 million global downloads [18]. This massive reach positions Pokémon Go as a large-scale, albeit unintentional, physical activity intervention. However, its actual effectiveness in promoting increased walking and fostering activity learn remains to be empirically validated.

This study aims to provide insights into large-scale interventions exemplified by Pokémon Go and explore the potential of leveraging games to enhance physical activity for public health purposes. We investigate Pokémon Go’s influence on physical activity by analyzing wearable sensor data and search engine query logs from 31,793 users over three months. Within this group, we identified 1420 Pokémon Go users based on their search activity and evaluated the game’s impact on their physical activity. We compared activity changes in Pokémon Go users to a control group of US wearable users and further contrasted Pokémon Go’s effect with four leading mobile health apps. Finally, we estimated Pokémon Go’s broader public health implications, focusing on its role in activity learn and behavior modification.

Our primary research questions are:

- Does playing Pokémon Go correlate with increased physical activity? What is the magnitude of this effect, and how long does it persist as a form of activity learn?

- Is this effect limited to specific subpopulations, or does it impact individuals across varying prior activity levels, ages, genders, and weight statuses, thus offering broad-based activity learn opportunities?

- How does Pokémon Go compare to leading mobile health apps in its capacity to modify physical activity behavior and promote activity learn?

- What has been Pokémon Go’s impact on physical activity in the United States, and what is its potential public health impact if sustained user engagement could be achieved in the realm of activity learn and healthy living?

To our knowledge, this is the pioneering study to integrate large-scale wearable and search sensor data to retrospectively assess large-scale interventions and the first to specifically examine the effect of Pokémon Go on activity learn and physical behavior.

Methods

Dataset

We combined search engine query data with physical activity measurements from wearable devices to provide a comprehensive view of activity learn. Specifically, our analysis integrated: (1) queries to the Microsoft Bing search engine containing “pokemon,” used to identify likely Pokémon Go players; and (2) daily step counts from Microsoft Band wearables, measuring physical activity. We utilized this combined dataset to quantify changes in physical activity before and after users showed strong indications of starting Pokémon Go.

The primary study population comprised 31,793 US users of Microsoft products who consented to link data from their Microsoft Band wearables and online activity for product usage understanding and improvement. We identified 1420 users as highly likely Pokémon Go players. We compared physical activity changes in this group with a control group of 50,000 randomly sampled US Microsoft Band users. Given the expected low prevalence of Pokémon Go players in this random sample [19], we believe it does not significantly affect our analysis. All users provided self-reported age, gender, height, and weight, enabling us to assess Pokémon Go’s effect across different user demographics in terms of activity learn.

This research was conducted while all authors were employed by Microsoft. The study was performed offline using data collected for existing business operations and did not influence user experience. All data were anonymized before analysis. The Ethics Advisory Committee at Microsoft Research deemed these precautions sufficient to exempt this work from detailed ethics review under the Common Rule.

Table 1. Representative experiential and nonexperiential Pokémon Go queries [20]. In total, 454 such features were used for classification of experiential queries.| Nonexperiential query | Experiential query |

|—|—|

| pokemon go | pokemon go iva calculator |

| pokemon go death san francisco | pokemon go teams |

| pokemon go robberies | how to play pokemon go |

| couple sues pokemon go | pokemon go guide |

| baltimore pokemon accident | pokemon go servers |

| pokemon games | pokemon go bot |

| bluestacksb pokemon go | pokemon go eeveec evolution |

aiv: It refers to individual values which are attribute points of Pokémon determining their stamina, attach, and strength.

bbluestacks: It refers to a method to play Pokémon Go on a desktop computer instead of the intended use in the real world.

ceeevee: It is the name of a Pokémon.

Identification of Pokémon Go Users Through Search Queries

We gathered all Bing search queries from any device (desktop, laptop, mobile) from the 31,793 users between July 6, 2016 (US release date) and August 23, 2016 (analysis date) that included “pokemon” (case-insensitive). We manually categorized the 454 most frequent unique queries as “experiential” [20,21] if they strongly suggested the user was actively playing Pokémon Go, rather than merely interested in news or general game information. This categorization was done by an author familiar with the game, who assessed each query and its search results to determine if it indicated game play. Table 1 provides examples of experiential and non-experiential queries, highlighting the nuances of activity learn related searches.

Of the 25,446 users who made any queries during our observation period, 1420 (5.58%) issued an experiential Pokémon Go query. This proportion closely aligns with the estimated 5.9% of regular Pokémon users in the US [19], indicating our search-based method effectively identifies a substantial number of Pokémon Go players and potential participants in activity learn. We used the timestamp of each user’s first experiential query as a proxy for their Pokémon Go start time (t0), representing their entry point into activity learn through the game.

Our experiential query method might slightly overestimate t0 if users queried after starting to play. However, underestimation is less likely due to the specific nature of experiential queries focused on gameplay details (Table 1). Importantly, any t0 overestimation leads to conservative effect estimates, as game-related activity increases might be incorrectly attributed to pre-t0 activity, thus ensuring a robust assessment of activity learn.

Measuring Physical Activity

We aimed to measure changes in physical activity before and after t0, the presumed start of Pokémon Go play and associated activity learn. We used daily steps recorded by the Microsoft Band’s 3-axis accelerometer and gyrometer. Accelerometer-based measures are preferred over subjective surveys, which can overestimate physical activity by up to 700% [22]. We analyzed step data from 30 days before t0 to 30 days after t0. At the study time, few users had played Pokémon Go longer than 30 days. All included Pokémon Go users had used wearable devices for a significant duration (median 433 days), ruling out device adoption as a factor in activity changes. Of the identified Pokémon Go users, 792 had step data for at least one day before and after t0 (Table 2). Our analysis focused on these users, comparing their activity to the control group. Varying the tracking period threshold (days before/after t0) did not significantly alter our findings regarding activity learn.

Table 2. Number of Pokémon Go users and number of days of steps tracking for these users included in the dataset. We counted days up to 30 days before and after each user’s first experiential query and only considered users with at least one day tracked before and after their first experiential query.| Minimum number of experiential Pokémon Go queries | Number of users | Number of days with steps data |

|—|—|—|

| 1 | 792 | 36,141 |

| 2 | 417 | 18,804 |

| 3 | 262 | 11,916 |

| 4 | 199 | 9132 |

| 5 | 143 | 6633 |

| 6 | 113 | 5186 |

| 7 | 85 | 3819 |

| 8 | 70 | 3131 |

| 9 | 56 | 2512 |

| 10 | 50 | 2218 |

Control Group

We further compared activity changes in Pokémon Go users to a control group—a random sample of US Microsoft wearable users—to isolate the game’s effect from external factors like seasonal activity variations. For example, summer and vacations might increase steps in the control group. As control users had no experiential queries, we needed a t0 proxy for comparison. This t0 reference point allowed us to measure activity changes before and after for both groups, ensuring a fair comparison of activity learn patterns. For Pokémon Go users, t0 was their first experiential query date (e.g., July 6 or 7, 2016). Using a single t0 (e.g., July 6, 2016, Pokémon Go launch) for all control users could confound weekend, weather, or other effects. Pokémon Go users had varied t0 values, mitigating such aligned effects. To match observation periods, we assigned control users the same t0 distribution as Pokémon Go users; each control user was randomly paired with a Pokémon Go user, adopting their t0 value. This ensured activity comparisons over comparable timeframes, crucial for accurate activity learn assessment.

Wear Time

We also measured daily wear time of activity trackers in half-hour increments. Changes in recorded steps could arise from wear time variations, not actual activity changes, potentially skewing activity learn interpretation. However, wear time remained effectively constant for both groups during the study, with group ratio changes <1%. Therefore, step count differences were attributed to genuine physical activity changes driven by Pokémon Go engagement and its impact on activity learn.

Measuring the Impact of Pokémon Go

We quantified Pokémon Go’s impact on physical activity by comparing pre- and post-t0 activity levels and correlating search query engagement with the magnitude of the activity effect, thus linking game engagement with activity learn outcomes.

Longitudinal Analysis

We compared physical activity trends of Pokémon Go users and the control group over time, relative to each user’s t0. Control group users were assigned randomized t0 values as described earlier. We measured average daily steps for 30 days pre-t0 and 30 days post-t0. Days with no step data were excluded for that user on that day. We calculated average activity separately for both groups. For graph clarity, we smoothed daily averages using Gaussian-weighted averaging (7-day window), but statistical tests used raw data. We estimated 95% confidence intervals using 500 bootstrap resamples [23].

Dose-Response Relationship Between Pokémon Go and Physical Activity

Established dose-response relationships exist between physical activity levels and health outcomes [4,24,25]. We hypothesized that higher Pokémon Go engagement, reflected in more experiential queries, would correlate with greater physical activity increases and enhanced activity learn. We quantified effect sizes as the difference in average daily steps pre- versus post-t0 across all users and days over 30-day periods, exploring the dose-response relationship between search-engine engagement and real-world physical activity within the context of activity learn.

Does Everyone Benefit?

We assessed the effect on individual user physical activity post-Pokémon Go initiation and linked effect magnitude to demographics: age, gender, BMI, and prior activity levels. We investigated if benefits were subgroup-specific or broadly applicable, indicating wide-reaching activity learn potential. The individual-level effect was defined as the difference in average daily steps 30 days pre- and post-t0. User-level analysis included only Pokémon Go and control users with ≥7 days of step tracking pre- and post-t0 (to reduce noise; day-level analysis used ≥1 day threshold). This yielded 677 Pokémon Go users and 26,334 control users.

Comparison With Existing Health Apps

We compared Pokémon Go’s effect to that of mobile health apps. Microsoft Band data included connections to other fitness/health apps, providing timestamps of initial connections (t0) for app users. We studied four leading mobile health apps (anonymized for legal reasons), consistently top-rated on iOS and Android, representing state-of-the-art consumer health apps. We measured daily steps 30 days pre- and post-app initiation (post-connection t0), focusing on users starting app use after July 1, 2016, to control for seasonality and ensure comparability with the Pokémon Go group regarding activity learn. Again, we restricted analysis to users with ≥7 days of step tracking pre- and post-t0 (Pokémon Go group) or app connection (comparison groups). For apps A, B, C, and D, we included 1155, 313, 625, and 296 users, respectively. These users had substantial wearable device usage history before app connection (median days: app A 87, app B 57, app C 103, app D 76). Thus, activity differences likely stemmed from app usage, not device adoption, highlighting the distinct impact of game-based activity learn versus traditional health apps. We lacked engagement data for these apps.

Estimating the Public Health Impact of Pokémon Go

To quantify Pokémon Go’s public health impact, we estimated: (1) total steps added to US user physical activity in the first 30 days, (2) changes in the proportion of users meeting physical activity guidelines before and after Pokémon Go, and (3) potential life expectancy impact if sustained user engagement were achieved, reflecting the long-term potential of activity learn initiatives.

Physical activity guidelines [7,8] equate to approximately 8000 daily steps [26,27]. Only 21% of US adults meet these guidelines. We used all users with ≥7 days of step tracking pre- and post-t0. We measured the proportion achieving >8000 average daily steps, both pre- and post-t0, repeated for Pokémon Go users with ≥1 and ≥10 experiential queries and for the control group, analyzing the game’s effect on achieving recommended activity learn levels.

Assuming sustained 1000 daily step increase from Pokémon Go, we estimated life expectancy impact. A 1000-step increase is associated with a 6% lower mortality risk. Using life-table analysis similar to [5] based on mortality risk estimates from [28] and the US 2013 Period Life Table [29], we estimated life expectancy changes based on mortality risk reduction, evaluating the long-term benefits of activity learn through gaming.

Results

Study Population Demographics

Demographic data for Pokémon Go and control users are in Table 3. Pokémon Go users were younger and less often female than average wearable dataset users. Gender bias may partly stem from data-linking consent demographics. However, gender-specific effect differences were insignificant. Overweight and obese user proportions mirrored US population averages [30], similar across Pokémon Go and control groups, indicating no weight-based selection bias. Pokémon Go users’ average activity level was lower than the control group, suggesting the game attracts less active individuals, a key demographic for activity learn interventions. Demographic differences were not matched between groups, as younger age and male gender typically correlate with higher activity [12]. However, demographic-specific effect variations were analyzed (see “Does Everyone Benefit?”).

Table 3. Dataset statistics.| Dataset statistic | Pokémon Go users | Wearable usersb |

|—|—|—|

| Number of users | 1420 | 50,000 |

| Number of users with sufficient activity data | 792 | 26,334 |

| Median age | 33 | 42 |

| % female | 3.8 | 25.7 |

| % underweight (BMIa<18.5) | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| % normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25) | 34.2 | 31.4 |

| % overweight (25≤BMI < 30) | 36.5 | 38.4 |

| % obese (30≤BMI) | 28.2 | 29.1 |

| Average daily steps overall | 6258 | 6435 |

aBMI: Body Mass Index

bWearable users refers to random sample of US Microsoft Band users. We only consider users with at least one day of steps tracking before and after the user’s first experiential query (“sufficient activity data”).

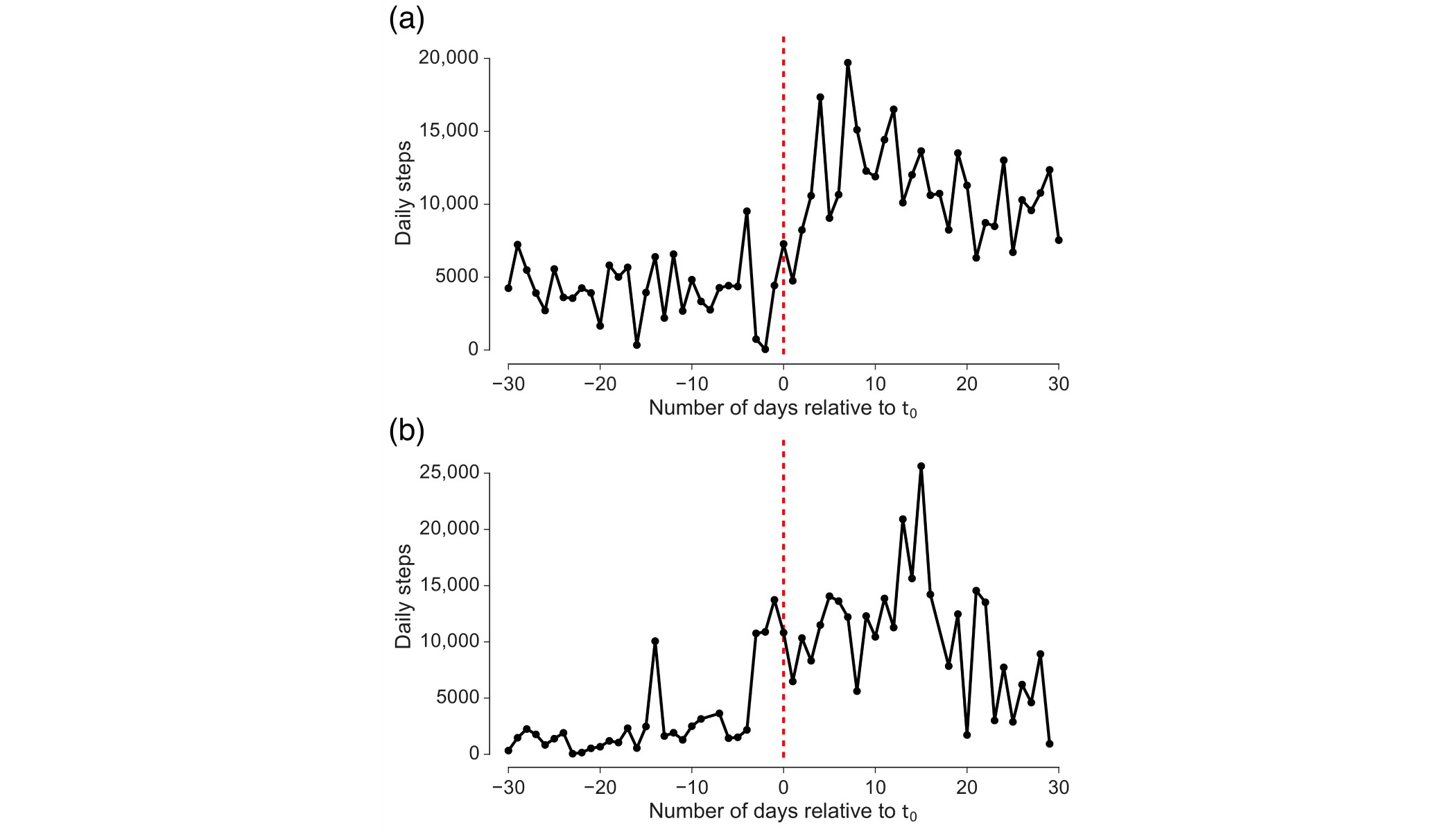

Example Time Series of Physical Activity

Figure 1 illustrates daily steps for two example users pre- and post-experiential query. Both users significantly increased activity post-Pokémon Go, by thousands of steps daily, demonstrating individual-level activity learn. We analyzed if this increase was representative and how it varied across individuals.

Longitudinal Analysis

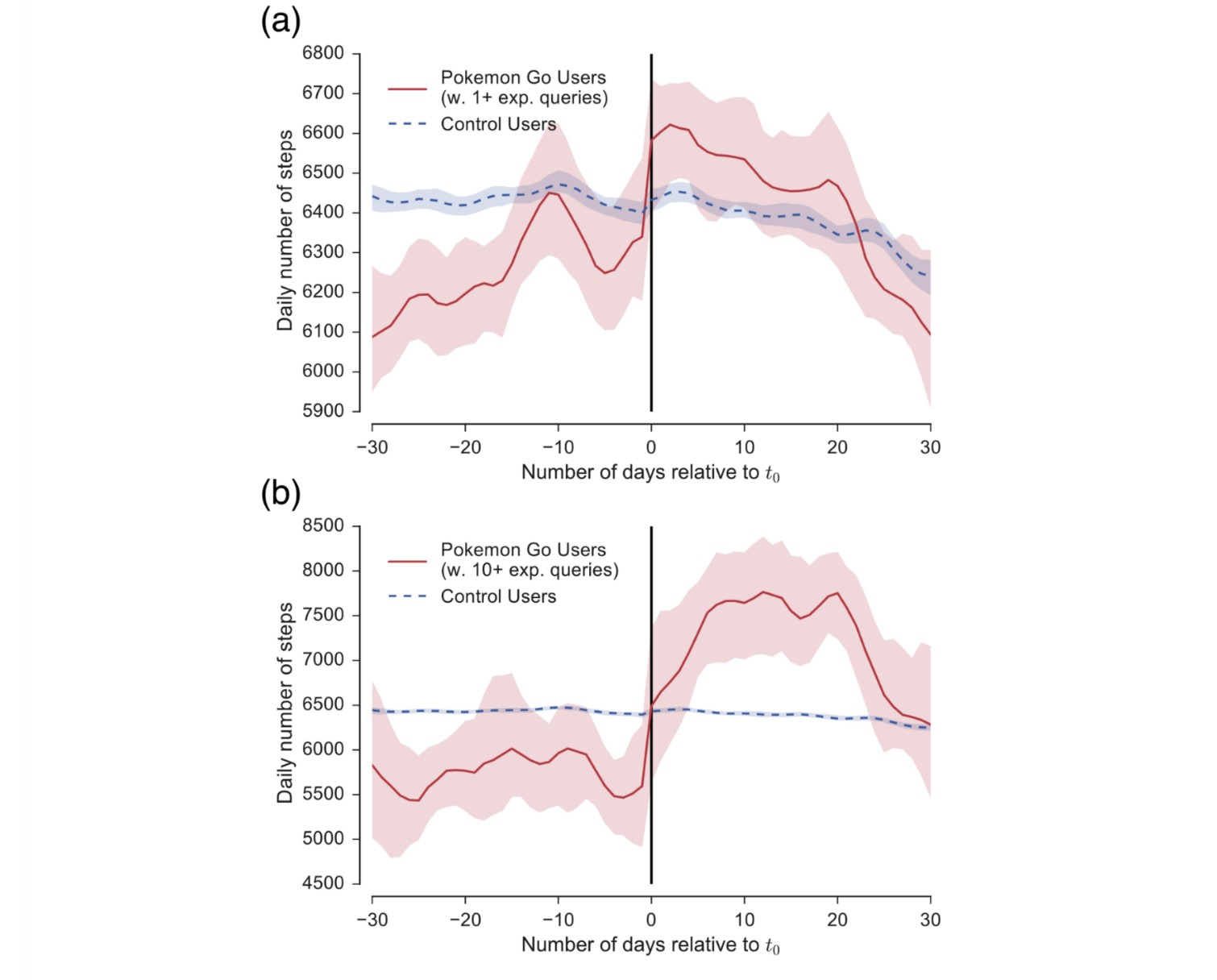

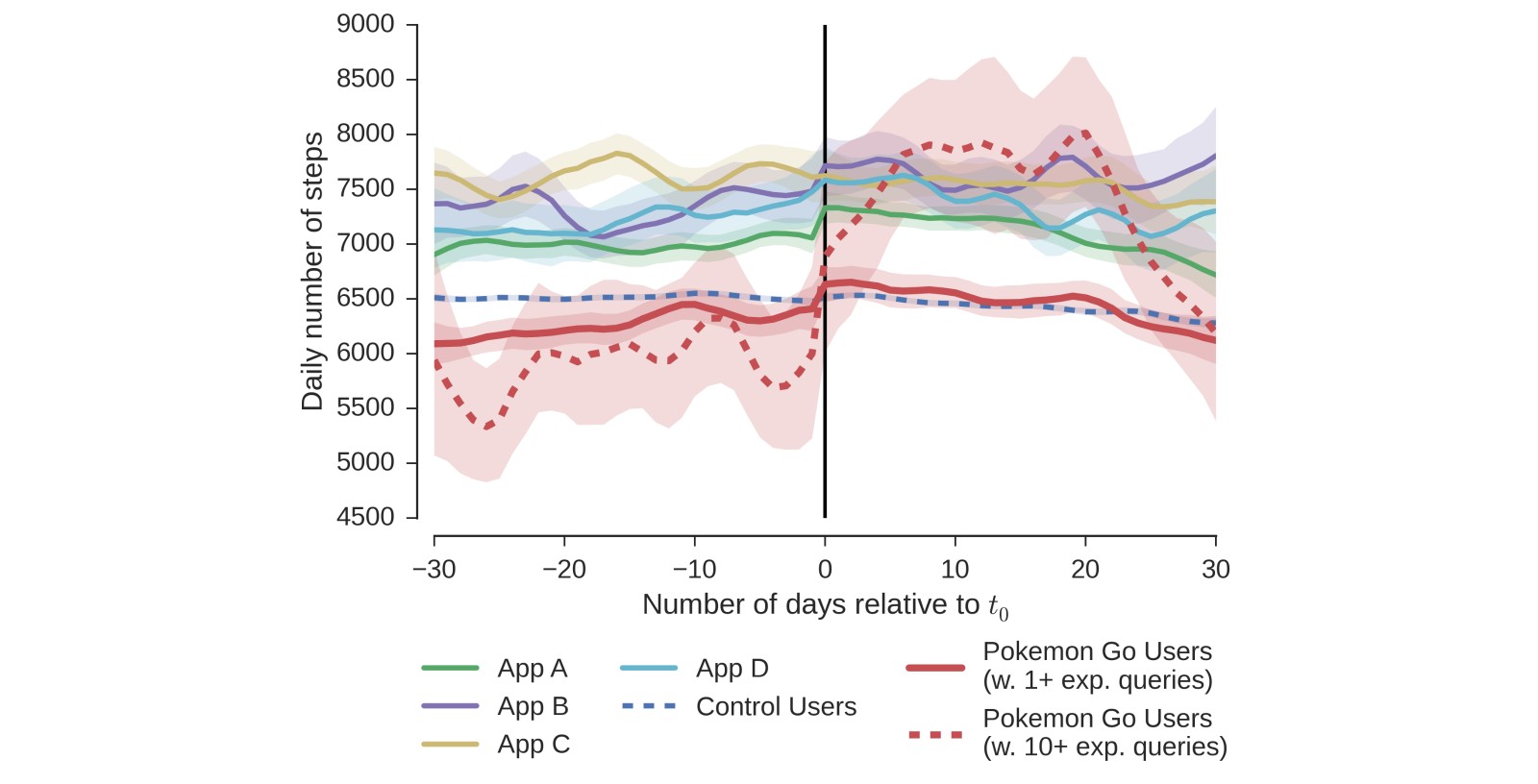

Pokémon Go initiation correlated with significant physical activity increases (Figure 2) versus the control group. The control group slightly decreased activity by 50 daily steps (P<.001; Mann-Whitney U-tests used unless stated). Pokémon Go users increased activity by 192 daily steps (P<.001). A sharp increase post-t0 suggested the increase stemmed from Pokémon Go engagement (P<.01, comparing 3 days pre- and post-t0), directly related to activity learn. Pokémon Go users initially had lower activity than average US Microsoft Band users (dashed blue line; 178 daily steps less; P<.001). Post-Pokémon Go, their activity surpassed the control group (65 daily steps more; P<.001). The activity increase 10 days pre-t0 was likely statistical noise due to t0 variation across users, not weekend or vacation effects.

Increases were greater for users with ≥10 experiential queries, indicating higher Pokémon Go interest (Figure 2, bottom). These users were initially less active (5756 daily steps vs. 6435 in control; P<.001). Post-Pokémon Go, they showed a large increase to 7229 daily steps (1473 daily step difference; P<.001), ~13% higher than the control (P<.001), suggesting a dose-response relationship between Pokémon Go interest and activity learn, analyzed further below.

Pre-t0 step increases could stem from game starts preceding experiential queries. However, sharp increases at t0 suggest the proxy for game start is largely valid. Activity decreased ~3-4 weeks post-t0 in both Pokémon Go groups (Figure 2). However, the more engaged group’s activity remained higher than their baseline, suggesting potential long-term behavior change and the need for long-term activity learn studies.

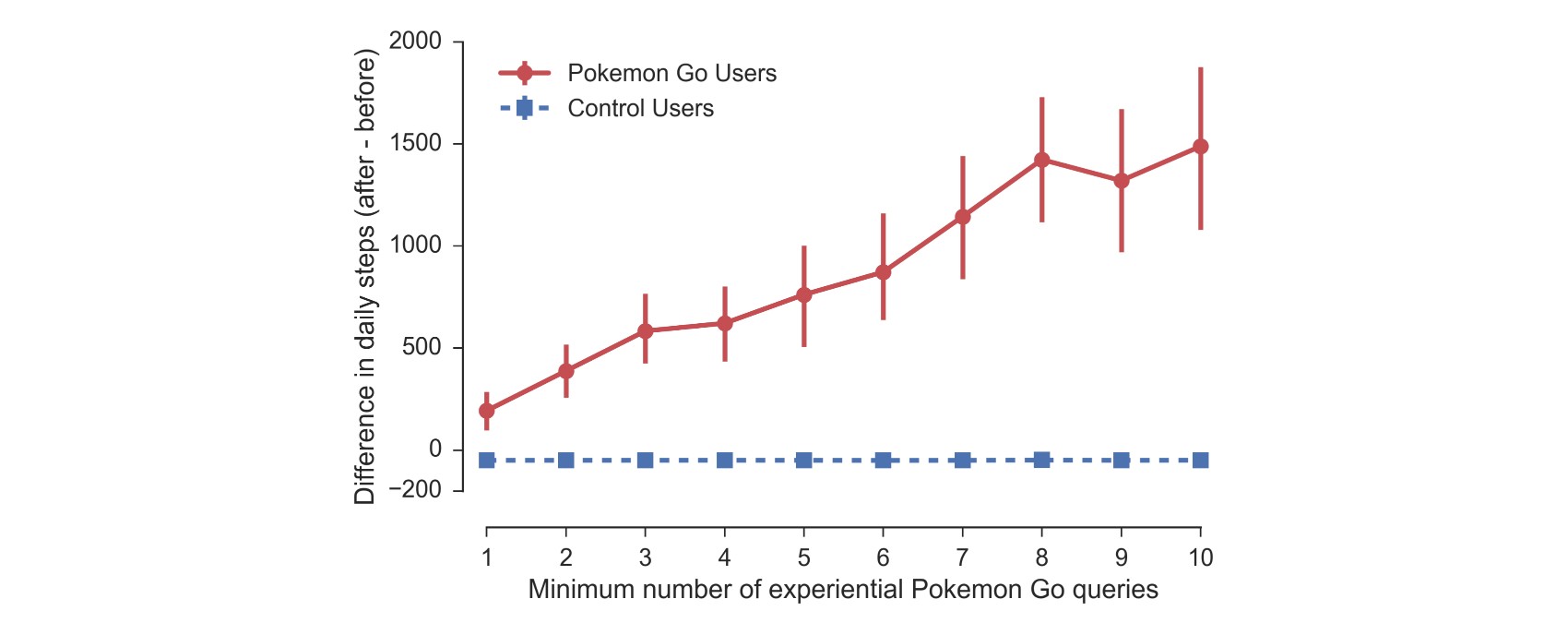

Dose-Response Relationship Between Pokémon Go and Physical Activity

A dose-response relationship existed between Pokémon Go engagement and activity effect (Figure 3). Users with more experiential queries showed greater activity increases, demonstrating a clear link to activity learn. Users with any Pokémon Go interest showed significant activity increases versus the control group (50-step decrease).

Step increases scaled roughly linearly with experiential query count: from 192 daily steps (3%) for ≥1 query to 1473 daily steps (26%) for ≥10 queries. Linear increase with query count suggests a causal link between Pokémon Go engagement and activity increases. Confounding factors unrelated to Pokémon Go wouldn’t explain this clear dose-response, strengthening the evidence for game-driven activity learn.

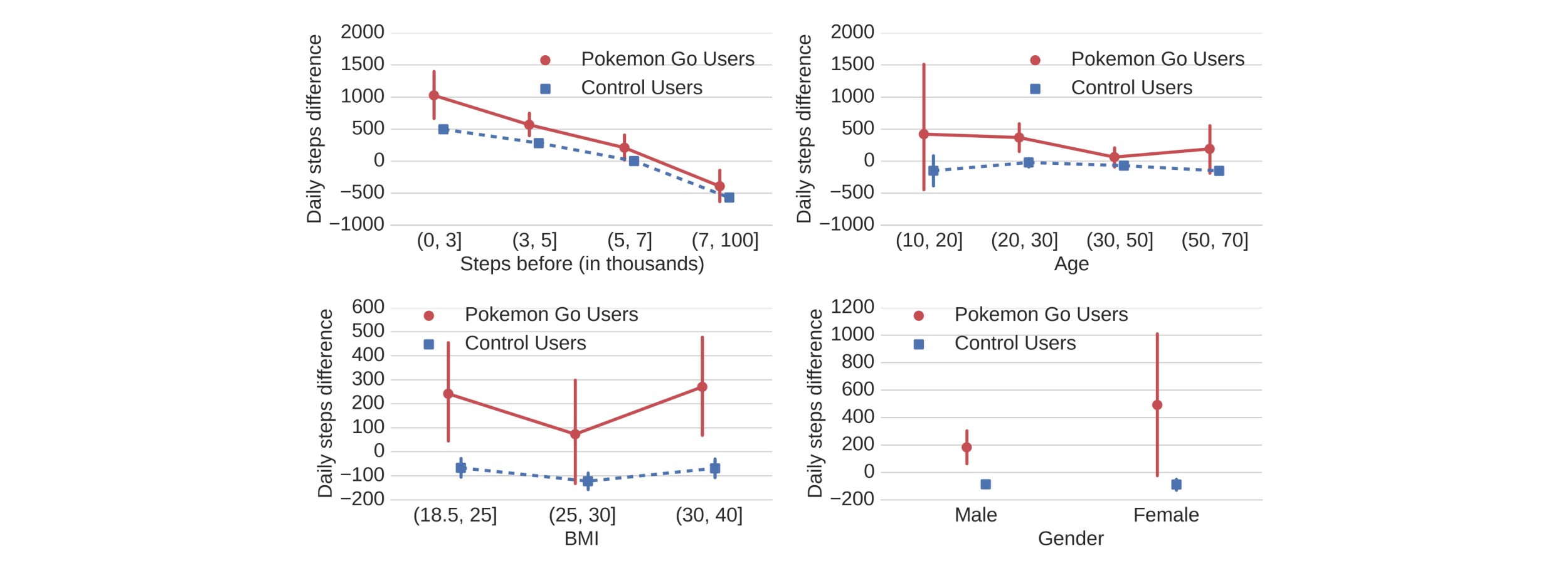

Does Everyone Benefit?

Pokémon Go increased activity across demographics: gender, age, BMI, and prior activity (Figure 4). Both Pokémon Go and control users with very low prior activity showed larger increases, while more active users showed decreases. However, Pokémon Go users showed greater increases across all prior activity levels (P<.025). Largest differences were in previously sedentary users (<5000 daily steps) [31]. Pokémon Go users showed greater activity increases across all age groups (P<.040, except small 10-20 year group), with largest effects in younger users (10-30 years), key age ranges for activity learn. Positive activity effect was consistent across BMI groups, encouraging given obese individuals (30<BMI≤40) are typically less active [32]. Pokémon Go group activity differences were always larger than control across BMI groups (P<.021). Activity differences were larger in Pokémon Go groups for both genders (P<.022). Increases for women were not significantly different from men (P=.110; small female sample).

Comparison With Existing Health Apps

Pokémon Go led to greater activity increases than mobile health apps and attracted less active users. Figure 5 visualizes average daily steps over time. Health app users were more active than average wearable users (6514 daily steps) even before app use (6997-7616 daily steps). Pokémon Go users were less active pre-game (5901-6265 daily steps). Health apps showed weak evidence of behavior change, except app A with a significant day-0 activity increase. However, app A’s increase was smaller than Pokémon Go’s. App A users increased activity by 111 daily steps (1.6%) versus 194 (1502) daily steps (3.1%, 25.5%) for Pokémon Go users with ≥1 (≥10) experiential queries. Highly engaged Pokémon Go users showed much larger activity increases than any health app users, highlighting the unique effectiveness of game-based activity learn.

Estimating the Public Health Impact of Pokémon Go

Effect on US Physical Activity

Users with ≥1 experiential query increased activity by 192 steps/day for 30 days. Extrapolating to 25 million US Pokémon Go users [16], Pokémon Go added 144 billion steps in 30 days to US physical activity – equivalent to 2724 equatorial circumferences or 143 moon round trips, a substantial contribution to national activity learn.

Effect on Meeting Activity Guidelines

Proportion meeting activity guidelines (8000 daily steps) remained constant for users with ≥1 experiential query (22.0% pre vs. 21.9% post-t0) and control users (24.1% vs. 23.5%), consistent with US adult estimates (21%) [7,8]. However, for highly engaged users (≥10 experiential queries), those achieving 8000 daily steps increased by 160% (12.2% pre vs. 31.7% post-t0), a significant relative increase in achieving recommended activity learn levels.

Effect on Life Expectancy

Highly engaged users increased activity by up to 1473 daily steps. Sustained 1000 daily step increase in 15-49 year olds could add 41.4 days to life expectancy. Across 25 million US Pokémon Go users [16], this translates to 2.825 million added life years. However, long-term effects require further study for a comprehensive understanding of activity learn and sustained health benefits.

Discussion

Principal Findings

Pokémon Go rapidly gained immense popularity, dominating media and reaching millions [16,17,18,19]. Health professionals noted potential benefits (increased activity, outdoor time, neighborhood exploration, social interaction, game challenge mastery) and risks (injury, safety, cost) [15,33]. This study precisely quantified Pokémon Go’s impact on physical activity across user groups, demonstrating its effectiveness as an activity learn tool.

Pokémon Go significantly increased physical activity at both group and individual levels over ~4 weeks. Greater Pokémon Go interest (more search queries) correlated with larger activity increases. Users with ≥10 queries increased activity by 1479 steps/day (26%).

Pokémon Go boosted activity across demographics, regardless of prior activity, age, weight, or gender. This is encouraging, suggesting broad positive effects, even for sedentary, obese, and older users. Reaching these groups is crucial for public health and effective activity learn strategies [15].

Comparison with health apps further indicated Pokémon Go’s ability to reach low-activity populations, unlike health/fitness apps that primarily attract active users. Low-activity populations benefit most from activity increases [7,8]. This highlights game-based interventions’ promise over traditional methods, often ineffective for low-activity individuals [13,14].

Pokémon Go significantly impacted US physical activity, adding ~144 billion steps, a massive contribution to activity learn nationwide. Highly engaged users were almost 3 times more likely to meet activity guidelines [7,8,26,27] post-game initiation. Sustained engagement could measurably improve US life expectancy, emphasizing the long-term potential of activity learn through gamification.

These results highlight the special role of activity-promoting games in public health. They attract diverse populations, including less active individuals, and drive significant activity increases with societal impact. However, sustaining long-term engagement and behavior change is crucial. Games may not appeal to everyone (e.g., male bias observed), and should complement, not replace, existing physical activity programs [2,9,10,11,12,14]. Designing engaging games and integrating them with health interventions is vital for future public health and activity learn initiatives. This study provides guidance on continuous and enhanced engagement strategies.

Limitations

Study limitations include a non-random US population sample (wearable device owners, data-sharing consent, predominantly male Pokémon Go users). Search queries as proxies for game play and engagement are also limitations, though validated by user fraction and dose-response findings. Demographics were self-reported. Follow-up was limited to 30 days; long-term effectiveness requires further study for sustained activity learn assessment.

Comparison With Prior Work

Few studies use wearable data to assess activity influences [34]. Medical studies often use accelerometer-defined activity [4,31,35] over self-reports. Pedometer/tracker use can increase activity [36,37], but findings are mixed [38]. Activity reminders showed short-term gains, but no significant changes after 6 weeks [38].

“Exergames” [39,40,41] and location-based games [42] aim to encourage activity, but none matched Pokémon Go’s popularity. These games are not yet integrated into physical activity programs, though some educational institutions are beginning to explore game-based activity learn [43]. Social influence in online networks can increase activity over months [44].

Search query logs are increasingly used to identify research subjects, e.g., for medication reactions and cancer screening [20,45]. Social media activity posts are studied for health behavior understanding [46,47,48], but not yet linked to ground-truth behavior or large-scale interventions.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, linking Pokémon Go and similar games to physical activity and health, and the first to combine wearable data with search engine queries to assess activity learn through gaming.

Conclusions

Novel mobile games requiring physical movement are effective complements to traditional interventions, reaching millions. Pokémon Go significantly increased physical activity over 30 days, especially in engaged users (1473 steps/day, 26% increase). Estimated 144 billion steps added to US activity and potential for 2.825 million added life years highlight the public health promise of activity learn through gamification. Long-term effects require further research. Geocentric games like Pokémon Go hold great promise for public health and sustained activity learn, warranting continued exploration and development.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted during an internship at Microsoft Research. All authors conceived the study, developed the methodology, and contributed to analysis and manuscript writing. The authors thank Jen Hicks for manuscript feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

This work was conducted while all authors were Microsoft employees, as part of their research roles, without external funding.

References

[1] Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):801-9. [doi:10.1503/cmaj.051351] [PMID: 16534088]

[2] US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

[3] Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012 Jul 21;380(9838):219-29. [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9] [PMID: 22818936]

[4] Manson JE, Hu FB, Rich-Edwards JW, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 26;341(9):650-8. [doi:10.1056/NEJM199908263410901] [PMID: 10460816]

[5] Ding D, Lawson KD, Richards J, Ainsworth M, James P, Kelly P, et al. The global burden of physical inactivity in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1311-24. [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-4] [PMID: 27475276]

[6] Ding D, Ricci C, Sharma S, Li KK, Foweather L, Roskams-Edris D, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016 Jul 30;388(10051):1311-24. [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30732-X] [PMID: 27475275]

[7] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult participation in recreational physical activity–United States, 2001 and 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Jan 15;59(1):9-12. [PMID: 20075848]

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014 Jun 13;63(4):1-168. [PMID: 24918634]

[9] Bauman AE, Bull FC, Chey T, Craig CL, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, et al. The IPAQ collaborative group: prevalence of insufficient activity in 11 countries using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Jun;41(6):1181-90. [doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a07bb4] [PMID: 19400340]

[10] Kohl HW 3rd, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012 Jul 21;380(9838):294-305. [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8] [PMID: 22818958]

[11] Hillsdon M, Thorogood M, Antiss T, Morris J. Randomised controlled trials of physical activity promotion in free living populations: a review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995 Dec;49(6):548-53. [doi:10.1136/jech.49.6.548] [PMID: 8847315]

[12] Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002 Sep;22(4 Suppl):73-107. [PMID: 11986264]

[13] King AC, Jeffery RW, Glasgow RE, Killen JD, Marcus BH. Developing new physical activity recommendations for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997 Jun;29(6 Suppl):S65-76. [PMID: 9215418]

[14] Marcus BH, Forsyth LH. Motivating people to be physically active. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2003.

[15] Bogost I. Pokémon Go and the revenge of augmented reality. Atlantic. 2016 Jul 11; . [URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/07/pokemon-go-and-the-revenge-of-augmented-reality/490734/] [WebCite Cache]

[16] Dredge S. Pokemon Go has 21m daily active users in the US, says SurveyMonkey. Guardian. 2016 Jul 14; . [URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jul/14/pokemon-go-daily-active-users-us-surveymonkey] [WebCite Cache]

[17] Takahashi D. Pokémon Go surpasses 40M downloads and is making $10M a day. VentureBeat. 2016 Jul 13; . [URL: https://venturebeat.com/2016/07/13/pokemon-go-surpasses-40m-downloads-and-is-making-10m-a-day/] [WebCite Cache]

[18] Makuch E. Pokemon Go hits 500 million downloads worldwide. Gamespot. 2016 Sep 08; . [URL: https://www.gamespot.com/articles/pokemon-go-hits-500-million-downloads-worldwide/1100-6443775/] [WebCite Cache]

[19] Newzoo. Pokémon GO explodes to 50 million users worldwide, but how sustainable is the success? 2016 Jul 29; . [URL: https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/pokemon-go-explodes-to-50-million-users-worldwide-but-how-sustainable-is-the-success/] [WebCite Cache]

[20] White RW, Tunkelang D. Evaluating search with user models. In: Baeza-Yates RA, Davison BD, de Rijke M, editors. Proceedings of the 31st Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 2008 Presented at: SIGIR ’08; July 20-24, 2008; Singapore. p. 3-10. [doi:10.1145/1390156.1390160]

[21] Teevan J, Dumais S, Horvitz E. Personalizing search via automated analysis of activity. In: Ghani R, Jones R, Jones-Kruml T, Marinier R, editors. Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining. 2005 Presented at: KDD ’05; August 21-24, 2005; Chicago, IL. p. 449-458. [doi:10.1145/1081870.1081922]

[22] Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008 Nov 06;5:56. [doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-56] [PMID: 18983977]

[23] Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993.

[24] Powell KE, Thompson PD, Caspersen CJ, Kendrick JS. Physical activity and the incidence of coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1987;8:253-87. [doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.001345] [PMID: 3555315]

[25] Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW 3rd, Barlow CE, Macera CA, Paffenbarger RS Jr, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996 Mar 20;275(14):1140-5. [PMID: 8569812]

[26] Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR Jr, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Ainsworth BE, Chan CB, et al. Step-determined physical activity classifications: accelerometer thresholds for classifying adults. Prev Med. 2005 Jul;40(6):638-45. [doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.001] [PMID: 15848147]

[27] Lee IM, Buchner DM. The importance of walking to public health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Jul;40(7 Suppl):S512-8. [doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c65ef] [PMID: 18562975]

[28] Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohl HW 3rd, Haskell W, Lee IM. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2011 Aug 23;124(7):789-800. [doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.010710] [PMID: 21859982]

[29] Arias E. United States life tables, 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015 Jun 23;64(11):1-64. [PMID: 26244775]

[30] Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):491-7. [doi:10.1001/jama.2012.39] [PMID: 22301009]

[31] Tudor-Locke C, Hatano Y, Pangrazi RP, Kang M. Revisiting “how many steps are enough?”. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Jul;40(7 Suppl):S529-37. [doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67bb] [PMID: 18562978]

[32] Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235-41. [doi:10.1001/jama.2009.2014] [PMID: 20071670]

[33] Richtel M, Tavernise S. Pokémon Go becomes a phenomenon, and Nintendo soars. New York Times. 2016 Jul 11; . [URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/12/technology/pokemon-go-becomes-a-phenomenon-and-nintendo-soars.html] [WebCite Cache]

[34] Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Wearable devices as facilitators, not drivers, of health behavior change. JAMA. 2015 Feb 17;313(5):459-60. [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.14781] [PMID: 25688741]

[35] Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Jan;40(1):181-8. [doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3] [PMID: 18091006]

[36] Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, Gienger AL, Lin N, Lewis R, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007 Nov 21;298(19):2296-304. [doi:10.1001/jama.298.19.2296] [PMID: 18029834]

[37] Kang M, Marshall SJ, Barreira TV, Lee CW, Tudor-Locke C. Effect of pedometer-based physical activity interventions: a meta-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2009 Dec;80(4):648-55. [doi:10.1080/02701367.2009.10592601] [PMID: 20088176]

[38] Van Achterberg T, Huisman J, Ketelaar NA, Oostendorp RA, Bleijenberg G. Effects of feedback on adherence and physical activity in patients receiving physiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2004 Nov;84(11):977-87. [PMID: 15509199]

[39] Baranowski T, Buday R, Thompson D, Lyons EJ, Lu AS, Baranowski J. Developing games for health behavior change: current perspectives. Games Health J. 2013 Feb;2(1):3-23. [doi:10.1089/g4h.2012.0008] [PMID: 24616757]

[40] Graves L, Ridgers ND, Stratton G. The contribution of active video games to children’s physical activity: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2010 Dec;50 Suppl 1:S3-11. [doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.001] [PMID: 19818852]

[41] Peng W, Lachman ME, Qin Y, Galper DI, Streeten EA. The effects of interactive dance video game exercise on physical and psychological well-being of older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011 Feb;66A(2):209-17. [doi:10.1093/gerona/glq195] [PMID: 21149393]

[42] Consolvo S, Klasnja P, McDonald DW, Avrahami D, Froehlich J, Harrison B, et al. Flowers or weeds?: evaluating the ecology of personal mobile sensors. In: Dourish P, Friday A, editors. Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Ubiquitous computing. 2006 Presented at: UbiComp ’06; September 17 – 21, 2006; Orange County, CA, USA. p. 54-71. [doi:10.1145/1174989.1174998]

[43] Perry J. Pokemon Go class at Cleveland State University is real. Cleveland.com. 2016 Jul 29; . [URL: https://www.cleveland.com/metro/2016/07/pokemon_go_class_at_cleveland.html] [WebCite Cache]

[44] Centola D. An experimental study of homophily in global-scale social networks. Science. 2011 Sep 02;334(6053):270-3. [doi:10.1126/science.1207051] [PMID: 21960529]

[45] White RW, Horvitz E. Cyberchondria is contagious: concern over online search results. In: Agichtein E, de Rijke M, Ishikawa T, editors. Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Conference on information and knowledge management. 2008 Presented at: CIKM ’08; October 26-30, 2008; Napa Valley, California, USA. p. 649-658. [doi:10.1145/1458082.1458170]

[46] Chung JE, Poland CA, Wermiel D, Seo M, Waterman C, Grande D. Social media use in a cohort of low-income patients with uncontrolled hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Sep;31(9):1293-9. [doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3752-5] [PMID: 27150375]

[47] Ferrara E, Yang Z. Quantifying the effect of virality in online social networks. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2015;1:e26. [doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.26] [PMID: 27119135]

[48] Salathé M, Bengtsson L, Bodnar TJ, Brewer DD, Brownstein JS, Buckee CO, et al. Digital epidemiology. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(7):e1002616. [doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002616] [PMID: 22829753]

Abbreviations

| BMI: body mass index |

|---|