Like a badge of honor, or perhaps a comical misdirection, the PARIS, TEXAS tattoo on my arm often sparks conversation. Yet, truth be told, BORAT: CULTURAL LEARNINGS OF AMERICA FOR MAKE BENEFIT GLORIOUS NATION OF KAZAKHSTAN holds the undisputed title of my all-time favorite film. Sacha Baron Cohen, in my view, isn’t just funny; he’s a comedic force of nature, arguably the most vital comedian of his generation.

Before diving in, take a moment to relive the brilliance:

[Watch this and then continue reading]

The anticipation for BORAT’s 2006 release was palpable. I vividly recall stumbling upon the trailer on StupidVideos.com, a now-nostalgic corner of the internet, predating YouTube’s dominance in online comedy. As a bewildered fifth grader in Bucharest, Romania, I was inexplicably drawn to this film. It was a must-see. Except, I missed it. Not from lack of trying, but due to a surprising twist: BORAT became the first film I can remember to receive an NC-17 rating in Romanian cinemas. The film wasn’t exactly embraced in Romania; anti-BORAT sentiment was definitely in the air. But more on that shortly.

My viewing became a waiting game, finally culminating almost a year later when my father returned from a business trip with a DVD. As the film began, the source of my initial intrigue became clear. The scenes depicting Kazakhstan were filmed in a Romanian village, a mere hour from my school. The film barely attempted to conceal this. Borat’s wife, Oxana, even spoke Romanian in her introduction (moments before her supposed bear-related demise). For me, Borat was Romania’s South Park. It ruffled feathers, yet I connected with its audacious willingness to mock its subjects, ultimately satirizing the Western world.

Now, you might be thinking: wasn’t I offended by this misrepresentation of my homeland?

My answer is a resounding “no,” though the reasons are nuanced. Romania had rarely been authentically depicted in Hollywood productions. While COLD MOUNTAIN used Romania as a stand-in for North Carolina, and Steven Seagal films seemed to find a budget-friendly backdrop in my country, we, the Romanian people, were never truly part of the cinematic narrative. Romania was always a generic ‘somewhere else,’ a vague Eastern European setting, either a brutalist city or a rustic countryside.

Cohen’s use of the Romanian village, while seemingly another instance of Hollywood using Romania as a stand-in, felt different. The wink to the audience, the obviousness that this was not Kazakhstan, allowed us in on the joke in a way many critics missed. Here was a Romanian woman, in a Romanian village, cursing at a major celebrity. It was a reclamation of sorts, a moment of national recognition after years of being a cinematic blank canvas! This crude invitation into the joke is where BORAT excelled. We, the audience, felt like we were in on the prank, alongside Cohen and his crew. We knew Kazakhs didn’t actually behave like this, and Romanians, well, maybe some do, but the point was satire. Offense at misrepresentation misses the larger point entirely.

To truly grasp BORAT’s approach, we need to rewind to 2001. Post-9/11 America was grappling with Afghanistan. The surge in Islamophobia, the Iraq War, and the broader military actions in the Middle East formed a potent mix of American imperialism during the Bush era and beyond. Modern America is, in many ways, a direct result of the political decisions made following the attacks of 9/11. With the rise of xenophobia, even extending to those from Pakistan being unfairly targeted with the same hate as those from Afghanistan (remember the comedian who rose to fame with a “dead terrorist” ventriloquist dummy routine?), Cohen’s decision to scrutinize American culture and expose its racist anxieties towards countries ending in “-stan” felt timely and necessary.

The Kazakh government’s displeasure with Cohen’s portrayal of their nation is understandable. The exaggerated depiction of an anti-Semitic, misogynistic culture was undoubtedly a point of contention. And, let’s be honest, nobody wants to be mistaken for Romania! However, my argument has always been that Cohen’s work served a much broader purpose. BORAT, often labeled a mockumentary, transcends that genre. The opening Kazakhstan segment is pure mockumentary absurdity, reminiscent of Taika Waititi’s WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS. But once Borat arrives in America, the film shifts gears. It becomes a documentary of sorts, closer in spirit to Michael Moore’s FAHRENHEIT 9/11 than Albert Brooks’ REAL LIFE. Were some moments staged? Perhaps. But they were all in service of uncovering a deeper truth about America.

BORAT was a monumental undertaking, Cohen’s comedic Sistine Chapel. A comprehensive examination of American culture through the Socratic method: giving his subjects just enough rope to reveal their true selves, baited by Borat’s seemingly innocent normalization of cultural taboos. The film was overflowing with iconic moments, so much so that the deleted scenes on the DVD were as entertaining as many other movies’ best bits. Yes, it exposed American intolerance, but it also highlighted the kindness and humor of many Americans, from the weatherman struggling to contain his laughter to the driving instructor patiently explaining chivalry to Borat. If Borat-the-character’s genius was in eliciting bigotry, then BORAT-the-movie’s triumph was reminding us of the enduring light amidst the darkness.

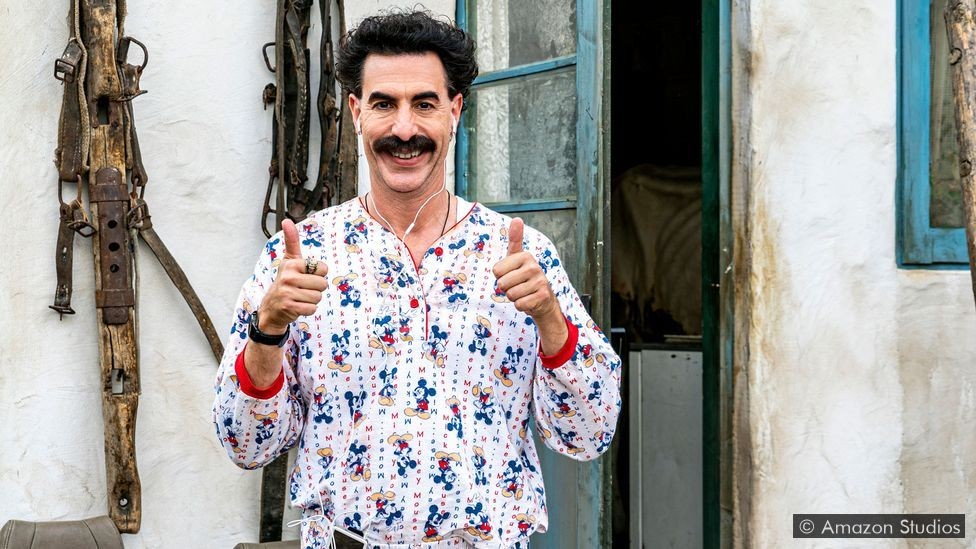

BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM marked Cohen’s return to the iconic grey (or is it blue?) suit. To say America was more divided in 2020 than in 2005 is a massive understatement. Ironically, the Bush years, once seen as deeply problematic, now hold a nostalgic glow for some Americans. Many of the hidden prejudices Cohen had to unearth in the first film were now openly displayed. In 2020, it takes mere minutes to discover someone’s QAnon beliefs. Given Borat’s established fame, Cohen needed a fresh approach. Simply exposing prejudice again wouldn’t suffice; it was already blatant. Cohen’s solution was twofold: a new face for Borat, and a satire focused on demonstrating why Americans should be ashamed of their prejudices.

The “new face” came in a series of hilarious and bewildering disguises. From Phillip Drummond III to Cliff Safari to John Chevrolet, Cohen drew from his WHO IS AMERICA? playbook, constantly shifting personas to deceive his unwitting subjects – a meta-disguise within disguises. This peaked when Borat, as Country Steve, led a “Throw The Jew Down The Well” singalong at a right-wing rally in Olympia, Washington, joined by AR-15 wielding attendees in singing “The Wuhan Flu.” It was a chilling scene, not just because of the armed, hate-singing crowd (the film wasn’t trying to re-prove American prejudice), but because of the speed and ease with which they participated.

Perhaps the most crucial “new face” was Maria Bakalova’s Tutar Sagdiev, Borat’s unexpected daughter. After a bizarre incident involving Kazakh porn star and Minister of Culture, Johnny The Monkey, Tutar embarks on a quest to marry Mike Pence (the implications are best left for the film to explain). Bakalova unlocked even more outrageous material, culminating in a now-infamous scene with Rudy Giuliani that truly must be seen to be believed. Utilizing techniques Cohen honed during WHO IS AMERICA?, Bakalova, equipped with a fabricated journalistic persona and right-wing press credentials, gained access to the former New York mayor.

These moments solidify the sequel’s success, especially considering it could have easily fallen flat (Cohen is not immune to missteps). BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM undeniably feels rushed. It’s a remarkably well-executed rush job, but the expedited production is palpable. It’s funny, but lacks the depth of the original. Many jokes feel like outtakes from the first BORAT. A scene where Borat awkwardly cuts a man’s hair, showing him each snipped lock, echoes a deleted scene from the original where Borat quizzes a grocery store worker about every cheese variety. The barbershop scene lacks the socio-political edge (unlike the grocery scene’s jab at capitalist excess), though it’s still amusing. The original, however, likely wouldn’t have included such a trivial moment, overshadowed by its stronger, more insightful documentary segments.

It’s a mixed bag. The highlights are monumental, the quieter moments a bit too subdued. But this is understandable given the original’s extensive road-trip footage versus the sequel’s adaptation to COVID-19 and a tighter, faster-paced narrative. BORAT gifted us a Kazakh journalist singing his national anthem at a rodeo and a naked hotel chase. It was pure chaos. BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM offers smiles and a touch of teary nostalgia, potentially bridging America’s cultural divide. BORAT was never partisan; its fanbase spans the political spectrum, from progressives seeking sharp satire to conservatives weary of overly-sensitive comedy.

Has Borat Sagdiev become more Americanized, or have Americans become more Borat-like? Can a fundamentally good person’s naivete and ignorance be a product of a dysfunctional environment? Much of this depends on how Cohen positions Borat within American culture. When Borat sings, “Kazakhstan, greatest country in the world, all other countries are run by little girls,” it echoes contemporary MAGA sentiments. Because beneath the absurdity, Borat possesses a surprising amount of good-naturedness. This is why Borat resonates more than Brüno or Ali G. He’s a lovable buffoon, well-meaning despite his ignorance, shaped by his country’s simplistic worldview. Cohen aims to expose prejudice, but much of BORAT’s commentary lies in engaging with those still open to change. This is why BORAT remains remarkably relevant.

Perhaps this also explains my appreciation for BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM’s expansion of Kazakh lore. BORAT boasts an underappreciated extended universe, especially when considering his appearances on THE ALI G SHOW. From the Tishnik Massacre celebration to Korky Buchek’s discography, there’s a rich fictional Kazakhstan to explore. BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM adds to this, revealing cow-related executions and the “true” origins of Coronavirus. It’s a wild ride, a treat for those familiar with Cohen’s Kazakh universe. It brought both laughter and a nostalgic tear. Is it as groundbreaking as the original? No. But it was timely, and arguably, more than we deserved.

Ultimately, Cohen’s return was perfectly timed. As a lifelong fan, being an extra chasing a Borat double through Bucharest (yes, they filmed in Romania again, even faking some American scenes there) was a dream. Though cut from the final film, I played a tiny part in this quirky piece of cinema. For someone who felt their country was (however crudely) brought into the cultural conversation by the original BORAT, being in the sequel felt bittersweet. Cohen’s continued nod to Romania, having Kazakh characters (like Dani Popescu’s Premier Nazarbayev) speak Romanian and giving Romania the closing credits song – a Fanfare Ciocarlia cover of “Just the Two of Us” – was deeply touching.