Escape Learning is a fundamental concept in behavioral psychology that describes how individuals or animals learn to end unpleasant situations. It’s a common experience, from simply leaving a noisy room to more complex behaviors aimed at alleviating discomfort. This article delves into the definition, origins, examples, strengths, weaknesses, and applications of escape learning, providing a comprehensive understanding of this essential learning process.

Escape Learning Definition and Origins

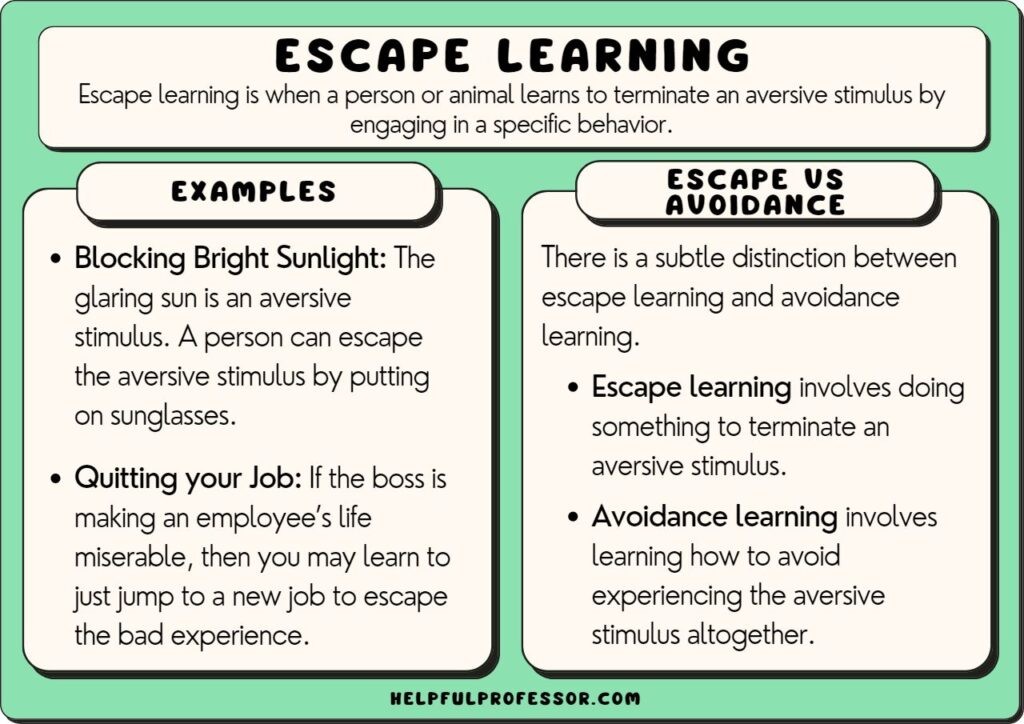

Escape learning is defined as the process by which an individual learns to perform a specific behavior to terminate an aversive stimulus. This concept was initially demonstrated through the groundbreaking work of B.F. Skinner, a pivotal figure in behaviorism. Skinner’s experiments using the Skinner Box, a controlled environment, provided the first empirical evidence of escape learning.

In a typical Skinner Box setup for escape learning, a rat would be placed in a metal cage with an electrified floor. The electric shock served as the aversive stimulus. Through trial and error, the rat would eventually discover that pressing a lever within the cage would stop the electric current. Initially, the rat’s pressing of the lever might be accidental. However, over time, the rat learns the contingency: lever pressing leads to the termination of the shock. Once this association is learned, the rat quickly learns to press the lever as soon as the electric shock begins, effectively escaping the unpleasant stimulus.

Diagram illustrating escape learning definition and examples in behavioral psychology

Diagram illustrating escape learning definition and examples in behavioral psychology

Skinner’s research on escape learning was instrumental in developing his theory of operant conditioning, also known as instrumental conditioning. Operant conditioning posits that the consequences of a behavior determine the likelihood of that behavior being repeated in the future. Behaviors that are followed by reinforcement (rewards) are strengthened and become more frequent, while behaviors followed by punishment are weakened and become less frequent.

While Skinner is widely recognized for his operant conditioning theory, it’s important to acknowledge the influence of Edward Thorndike’s Law of Effect. Published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Thorndike’s Law of Effect laid the groundwork for operant conditioning. It states that behaviors producing satisfying outcomes in a given situation are more likely to recur in that situation, whereas behaviors producing discomforting outcomes are less likely to be repeated. Escape learning aligns perfectly with the Law of Effect, as terminating an aversive stimulus provides a “satisfying effect,” thereby reinforcing the escape behavior.

Escape Learning vs. Avoidance Learning

It’s crucial to distinguish escape learning from avoidance learning, as these two concepts are often discussed together and can be easily confused. While both involve aversive stimuli, they differ in the timing and nature of the learned response.

Escape learning is about reacting to an aversive stimulus that is already present. The behavior is performed during the presentation of the aversive stimulus to stop it. In essence, you are “escaping” from something that is currently happening.

Avoidance learning, on the other hand, is about preventing the aversive stimulus from occurring in the first place. It involves learning to respond to a cue or signal that predicts the onset of an aversive stimulus. The behavior is performed before the aversive stimulus begins, to “avoid” it altogether.

Consider the Skinner Box example again. To demonstrate avoidance learning, researchers would introduce a discriminative stimulus, such as a light, before the electric shock. Initially, the rat only presses the lever after the shock starts (escape learning). However, with repeated pairings of the light and the shock, the rat learns to associate the light with the impending shock. In avoidance learning, the rat learns to press the lever as soon as the light comes on, thereby preventing the electric shock from ever occurring.

Avoidance learning can be further categorized into active and passive avoidance.

- Active avoidance involves taking action to avoid the aversive stimulus. In the Skinner Box example, pressing the lever when the light appears is active avoidance.

- Passive avoidance involves not taking action to avoid the aversive stimulus. For instance, if a rat learns that a specific area of the cage floor is electrified following a certain sound, passive avoidance would be the rat simply staying away from that area when the sound is heard. No active behavior is performed; avoidance is achieved by inaction.

Escape Learning Examples

Escape learning is prevalent in everyday life, across various contexts. Here are several examples illustrating how escape learning manifests in different situations:

- Using an Umbrella in the Rain: Rain is the aversive stimulus – it’s uncomfortable and can make you wet and cold. Opening an umbrella is the escape behavior that terminates the unpleasant experience of being rained on.

- Turning Down the Volume: Loud noise, whether from music, traffic, or construction, can be an aversive stimulus, causing discomfort or stress. Turning down the volume or moving to a quieter place is escape learning in action.

- Taking off Tight Shoes: Wearing shoes that are too tight can become increasingly uncomfortable and even painful throughout the day. Taking off the tight shoes is an escape behavior that immediately terminates the discomfort.

- Leaving a Smoky Room: Exposure to smoke, whether from cigarettes or a fire, is an aversive stimulus due to its irritating and potentially harmful nature. Leaving a smoky room is an escape response that removes you from the unpleasant environment.

- Applying Bug Spray: Mosquito bites and insect stings are aversive stimuli, causing itching, pain, and potential allergic reactions. Applying bug spray is a proactive escape behavior to prevent or reduce the likelihood of these unpleasant encounters.

- Seeking Shade on a Hot Day: Excessive heat and direct sunlight can be aversive, leading to overheating, sunburn, and discomfort. Moving into the shade is an escape behavior that provides relief from the heat and sun.

- Taking Medicine for a Headache: Headaches are a common aversive stimulus, causing pain and discomfort. Taking pain medication like aspirin is an escape behavior to eliminate the headache and its associated unpleasantness.

- Changing Jobs to Escape a Toxic Workplace: A toxic work environment, characterized by bullying, excessive stress, or unfair treatment, can be a prolonged aversive stimulus. Changing jobs, while a significant step, can be seen as an escape behavior to terminate the negative work situation.

- Ending a Discomforting Conversation: Being engaged in a conversation that is awkward, confrontational, or distressing can be an aversive social stimulus. Politely ending the conversation is an escape behavior to alleviate the discomfort.

- Using Noise-Canceling Headphones in a Busy Office: The constant noise and distractions of a busy office can be an aversive stimulus, hindering concentration and causing stress. Using noise-canceling headphones is an escape behavior to create a quieter and more focused work environment.

These examples demonstrate the wide range of situations where escape learning plays a role in our daily lives, helping us navigate and mitigate unpleasant experiences.

Strengths of Escape Learning

Escape learning is a powerful and adaptive learning mechanism with several key strengths:

1. Survival and Adaptive Value

From an evolutionary perspective, escape learning is fundamentally adaptive and crucial for survival. The ability to quickly learn to escape from harmful or threatening situations is essential for both humans and animals. Our innate predisposition to avoid pain, discomfort, and danger is rooted in escape learning.

Imagine early humans encountering a predator. The immediate, aversive stimulus of a dangerous animal triggers a flight response – running away is an escape behavior that dramatically increases the chances of survival. Similarly, escaping from extreme weather conditions, such as seeking shelter from a storm or intense heat, is vital for physical well-being.

This survival value extends to less dramatic, everyday situations as well. Escaping from a burning stove to avoid injury, or moving away from a source of noxious fumes, are all examples of escape learning that protect us from harm.

2. Immediate Relief and Reinforcement

Escape learning is inherently reinforcing because it provides immediate relief from an aversive stimulus. This immediate reduction in discomfort or pain strongly reinforces the escape behavior, making it more likely to be repeated in similar situations.

For instance, when you have a headache and take pain medication, the relief you experience after the medication takes effect is a powerful reinforcer for taking medication the next time you have a headache. The direct and rapid link between the escape behavior and the termination of the aversive stimulus makes escape learning very effective.

3. Psychological Well-being in Specific Contexts

In certain situations, particularly for individuals with sensory sensitivities or emotional vulnerabilities, escape learning can be psychologically adaptive, even if it appears maladaptive to others.

Consider children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who may experience sensory overload in noisy or crowded environments like classrooms. For these children, the classroom environment can become an intensely aversive stimulus, triggering anxiety and distress. Behaviors like leaving the classroom or covering their ears are escape responses. While these behaviors might be seen as disruptive in a typical classroom setting, for the child with ASD, they are adaptive mechanisms to manage overwhelming sensory input and maintain emotional equilibrium. In such cases, understanding escape learning helps educators and caregivers develop supportive strategies rather than simply suppressing the escape behaviors.

Weaknesses of Escape Learning

Despite its adaptive advantages, escape learning also has potential drawbacks:

1. Missed Opportunities for Learning and Growth

While escape learning is valuable for avoiding immediate threats, relying too heavily on escape behaviors can lead to missed opportunities for learning, growth, and personal development. Constantly escaping challenging or uncomfortable situations can prevent individuals from developing coping skills, resilience, and the ability to overcome obstacles.

For example, if a student consistently avoids challenging academic tasks by engaging in disruptive behavior to get sent out of the classroom, they are escaping the aversive stimulus of academic difficulty. However, this escape behavior prevents them from learning the material, developing problem-solving skills, and building academic confidence. In the long run, this pattern of escape learning can hinder their educational progress and limit their future opportunities.

Similarly, in professional settings, consistently escaping from demanding projects or difficult colleagues might provide temporary relief from stress but can also impede career advancement and personal growth. Confronting challenges, developing resilience, and learning to navigate difficult situations are often essential for long-term success and fulfillment.

2. Potential for Maladaptive Escape Behaviors

Escape learning can sometimes lead to the development of maladaptive behaviors, especially when healthy escape routes are not available or when individuals learn to escape through harmful or inappropriate means.

Substance abuse can be seen as a maladaptive escape behavior. Individuals may turn to drugs or alcohol to escape from chronic stress, emotional pain, or difficult life circumstances. While substance use may provide temporary relief from these aversive stimuli, it ultimately creates more significant problems, including addiction, health issues, and social difficulties.

Similarly, in interpersonal relationships, consistently withdrawing or avoiding conflict might be a learned escape behavior to avoid uncomfortable confrontations. However, this pattern of escape can damage relationships, prevent effective communication, and hinder the resolution of underlying issues.

3. Reinforcement of Avoidance and Anxiety

In some cases, escape learning can inadvertently reinforce avoidance behavior and contribute to the maintenance of anxiety disorders. This is particularly relevant in the context of phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

For instance, someone with a phobia of spiders might learn to escape situations where they might encounter spiders, such as avoiding hiking trails or basements. Each time they successfully avoid a potential spider encounter, their anxiety is reduced, reinforcing the avoidance behavior. This escape learning pattern can perpetuate the phobia, making it more entrenched over time.

In OCD, compulsive behaviors are often driven by escape learning. Individuals with contamination obsessions might engage in excessive hand-washing to escape the anxiety and discomfort associated with the fear of germs. The hand-washing behavior temporarily reduces their anxiety, reinforcing the compulsion and creating a cycle of obsessions and compulsions.

Applications of Escape Learning

Understanding escape learning has significant practical applications in various fields, including:

1. Understanding and Treating Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

As mentioned earlier, escape learning plays a crucial role in the development and maintenance of OCD. The repetitive behaviors (compulsions) in OCD are often escape behaviors aimed at reducing the anxiety and distress caused by intrusive thoughts (obsessions).

For example, in contamination OCD, the obsession is the fear of germs, and the compulsion is excessive hand-washing. The hand-washing is an escape behavior designed to terminate the aversive stimulus of anxiety related to contamination. Understanding this escape learning mechanism is essential for developing effective treatments for OCD.

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) therapy, a gold-standard treatment for OCD, directly addresses the escape learning cycle. ERP involves gradually exposing individuals to their obsessions (e.g., touching a contaminated object for someone with contamination OCD) while preventing them from engaging in their compulsions (e.g., preventing hand-washing). By blocking the escape behavior, ERP helps break the cycle of reinforcement and allows individuals to learn that their anxiety will naturally decrease over time without resorting to compulsions.

2. Addressing Classroom Escape Behavior

Escape learning is frequently observed in classroom settings, particularly among students with learning disabilities or behavioral challenges. Students may engage in disruptive behaviors, such as tantrums, refusing to work, or running out of the classroom, as escape mechanisms to avoid academic tasks or overwhelming classroom environments.

These escape behaviors, while understandable from the student’s perspective, can be detrimental to their learning and social development. They result in missed instructional time, fewer opportunities for social interaction, and can impede the acquisition of essential skills.

Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) is a valuable tool for addressing classroom escape behavior. FBA is a systematic process of gathering information to understand the function or purpose of a student’s behavior. In the context of escape behavior, FBA aims to identify the specific aversive stimuli that the student is trying to escape (e.g., academic demands, social situations, sensory overload) and the escape behaviors they employ.

Once the function of the behavior is understood, educators can develop interventions that address the underlying need for escape while teaching the student more adaptive coping strategies. This might involve modifying academic tasks to make them more manageable, providing sensory breaks for students sensitive to classroom noise, or teaching students to request help or ask for a break appropriately. By addressing the root causes of escape behavior and teaching replacement behaviors, educators can create more supportive and effective learning environments.

Conclusion

Escape learning is a fundamental and ubiquitous learning process that enables individuals and animals to terminate aversive stimuli by engaging in specific behaviors. It is a powerful adaptive mechanism that has played a crucial role in survival throughout evolution and continues to shape our daily actions. From simple actions like using an umbrella in the rain to more complex behaviors aimed at alleviating stress or discomfort, escape learning is a constant influence on our behavior.

While escape learning is generally adaptive, it’s important to recognize its potential downsides. Over-reliance on escape behaviors can lead to missed opportunities for growth, maladaptive coping strategies, and the reinforcement of anxiety. Understanding the principles of escape learning is essential for addressing various behavioral challenges, from classroom escape behavior to the complexities of OCD. By recognizing the function of escape behaviors and developing strategies to teach more adaptive responses, we can harness the power of learning to promote well-being and personal growth.

References

Beavers, G. A., Iwata, B. A., & Lerman, D. C. (2013). Thirty years of research on the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46, 1–21.

Bruni, T. P., Drevon, D., Hixson, M., Wyse, R., Corcoran, S., & Fursa, S. (2017). The effect of functional behavior assessment on school‐based interventions: A meta‐analysis of single‐case research. Psychology in the Schools, 54(4), 351-369.

Carr, J. E., Severtson, J. M., & Lepper, T. L. (2009). Noncontingent reinforcement is an empirically supported treatment for problem behavior exhibited by individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(1), 44-57.

Chazin, K. T., Velez, M. S., & Ledford, J. R. (2022). Reducing escape without escape extinction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of escape-based interventions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 31(1), 186-215.

Gray, P. (2007). Psychology (6th ed.). Worth Publishers, NY.

Gresham, F., Watson, T., & Skinner, C. (2001). Functional behavioral assessment: Principles, procedures, and future directions. School Psychology Review, 30, 156-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2001.12086106

March, R. E., & Horner, R. H. (2002). Feasibility and contributions of functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10(3), 158-170.

Manning, E. E., Bradfield, L. A., & Iordanova, M. D. (2021). Adaptive behaviour under conflict: Deconstructing extinction, reversal, and active avoidance learning. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 120, 526-536.

McComas, J., Hoch, H., Paone, D., & El-Roy, D. (2000). Escape behavior during academic tasks: A preliminary analysis of idiosyncratic establishing operations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 479–493.

Schmidt, J. D., Luiselli, J. K., Rue, H., & Whalley, K. (2013). Graduated exposure and positive reinforcement to overcome setting and activity avoidance in an adolescent with autism. Behavior Modification, 37, 128–142.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Staddon, J. E., & Cerutti, D. T. (2003). Operant conditioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 115-144.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. The Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements, 2(4), i.

Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology. New York: A. G. Seiler.

Wilder, D., Normand, M., & Atwell, J. (2005). Contingent reinforcement as treatment for food refusal and associated self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38, 549–553.