If you’re a parent or educator guiding a young child’s first steps into reading, you’re likely familiar with sight words. Often, children come home with lists – sometimes dozens, even hundreds – of words to memorize. The task of drilling these lists can feel overwhelming, leaving you questioning if your child is truly learning to read or simply becoming adept at rote memorization. It’s a common source of stress for both children and adults involved in their learning journey.

Perhaps you’ve been told that memorizing sight words is the primary way to learn to read. However, while sight words are undeniably important, relying solely on memorization can be an inefficient approach. It might not equip your child with the fundamental skills needed to decode the vast number of words they’ll encounter throughout their education and life.

This isn’t to say that sight words are unimportant. They are crucial for fluent reading. The key is understanding that there are more and less effective methods for teaching them. Before even tackling a sight word list, there are foundational skills that can make the process significantly easier and more impactful.

In this article, we’ll explore how to teach sight words in a way that empowers children not just to recognize specific words on a list, but to develop into confident and capable readers of almost any word they encounter.

Understanding Sight Words: What Are They?

Let’s begin by defining what sight words truly are.

Sight words are words that a reader recognizes instantly, effortlessly, and without needing to decode them. This automatic recognition is essential for fluent reading.

The number of sight words a person knows grows with their reading experience. A child just starting to read might have a sight word vocabulary of around a hundred words. In contrast, an experienced reader possesses a sight word vocabulary encompassing thousands upon thousands of words. Think about your own reading – you instantly recognize words like “the,” “and,” “is,” and countless others without consciously sounding them out. These are your sight words.

The sheer volume of sight words we need to know – thousands – is precisely why relying on memorizing lists of 50 or 100 words can be limiting. Imagine attempting to memorize each of these words individually; it would be an arduous and nearly impossible task.

Debunking the Myth: “Sight Words Can’t Be Sounded Out!”

A common misconception is that sight words are inherently irregular and cannot be decoded using phonics. You might have heard that “sight words just have to be memorized because you can’t sound them out.”

However, this isn’t entirely accurate. In fact, research indicates that approximately 90% of English words are decodable, meaning they can be sounded out using phonetic principles.

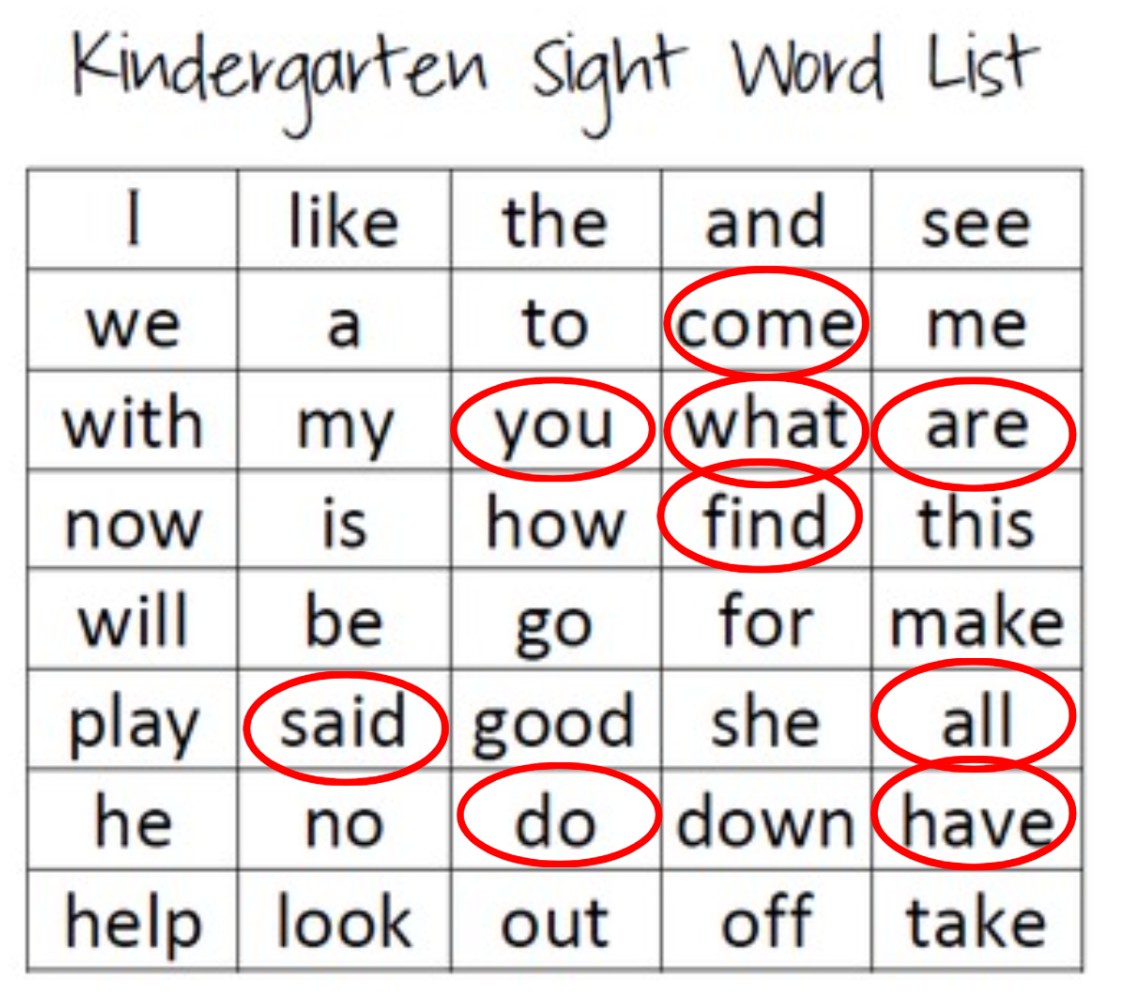

Consider a typical kindergarten sight word list. Let’s analyze how many words are actually decodable. Even with basic knowledge of single-letter sounds, a child can decode a significant portion of these words. With an understanding of common vowel combinations and two-letter sounds, the number of decodable words increases dramatically.

While some words, often referred to as “tricky words,” might have irregularities, many of these can be explained by a few phonics rules or exceptions. We’ll delve deeper into strategies for teaching these “tricky words” later.

Why Memorization Falls Short for Reading Development

You might wonder, “Even if many sight words can be sounded out, why does it matter? Is there really a downside to memorizing them if it gets the job done?”

The answer is yes, it matters significantly. Understanding how to decode words is fundamental for long-term reading development. Phonemic awareness, the ability to hear and manipulate sounds in spoken words, and phonics skills, the understanding of the relationship between letters and sounds, are the bedrock upon which proficient reading is built.

Think of it this way: if a child memorizes a list of 100 sight words, they can read those specific 100 words. But if they learn the skill of decoding, they gain the ability to read thousands upon thousands of words, even words they’ve never encountered before.

This ability to decode unlocks a world of reading. Children are no longer limited to pre-selected texts or topics. They can explore a vast range of books, delve into subjects that genuinely interest them, and develop a lifelong love of reading. Furthermore, when reading becomes fluent and effortless, cognitive resources are freed up to focus on comprehension, leading to a deeper understanding of what is read.

The Science of Reading: Research-Backed Approaches

The idea that whole-word memorization is the most effective way to teach reading is not supported by scientific research. Decades of studies in the field of reading science have consistently pointed towards the importance of systematic phonics and phonemic awareness in developing proficient readers.

Researchers emphasize that learning to read is not a natural process like learning to speak. It requires explicit instruction in the alphabetic principle – the understanding that letters represent sounds and that these sounds can be blended together to form words. This is the core of phonics instruction.

Cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, in his book Reading in the Brain, explains the complex neural pathways involved in reading and highlights the brain’s efficiency in processing words through phonological decoding rather than solely relying on visual memorization. Understanding this science underscores the importance of phonics-based approaches in early reading instruction.

Kindergarten sight word list highlighting tricky words

Kindergarten sight word list highlighting tricky words

A typical kindergarten sight word list with “tricky words” circled, illustrating that many sight words are indeed decodable with phonics knowledge.

Effective Strategies: How to Teach Sight Words for Reading Success

So, if rote memorization isn’t the ideal approach, how do you effectively teach sight words? The answer lies in a balanced approach that prioritizes phonics while providing targeted strategies for those truly “tricky words.”

Here’s a step-by-step guide to teaching sight words in a way that builds strong reading skills:

-

Prioritize Phonics Foundations: Before directly tackling sight word lists, ensure your child has a solid foundation in phonics. This includes:

- Phonemic Awareness: Activities that develop the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. Examples include rhyming games, segmenting sounds in words (e.g., breaking down “cat” into /c/-/a/-/t/), and blending sounds together.

- Letter-Sound Correspondence: Explicitly teach the sounds of letters and letter combinations. Start with single letter sounds and gradually introduce digraphs (e.g., “sh,” “ch”) and vowel teams (e.g., “ai,” “ea”).

-

Decode First, Memorize Second: When introducing a sight word, encourage your child to attempt to decode it using their phonics knowledge. Many words on typical sight word lists are decodable! This reinforces their phonics skills and builds confidence.

-

Address “Tricky Words” Strategically: For words that are genuinely “tricky” due to irregular spellings or phonics patterns not yet learned (like the circled words in the image above), use a targeted approach:

- Identify the Tricky Part: Show the word and explain, “This word is a little tricky because part of it sounds different from how we might expect.”

- Highlight Decodable Parts: Point out the parts of the word that can be sounded out using known phonics rules. This helps children see the familiar within the unfamiliar.

- Explicitly Teach the Irregularity: Focus on the specific part of the word that makes it “tricky.” For example, with the word “said,” explain that the “ai” is making an /e/ sound in this word.

- Blend and Read: Guide your child to blend the sounds they know with the newly explained “tricky” sound to read the whole word.

Example: Teaching the “Tricky Word” – “Said”

- Show the word “said.”

- Explain: “This word is ‘said.’ It’s tricky because the ‘ai’ part sounds like /e/ in this word, not like in ‘rain’.”

- Point to “s” and “d” and say their sounds: “/s/…” “/d/…”

- Explain the “ai” makes an /e/ sound here.

- Blend: “/s/ … /e/ … /d/ … said.”

-

Multisensory Learning: Engage multiple senses to enhance memory and learning:

- Visual: Use flashcards, write words on whiteboards, use different colors to highlight tricky parts.

- Auditory: Say the word aloud, have the child repeat it, emphasize sounds within the word.

- Kinesthetic/Tactile: Have children trace words in sand or rice, build words with letter tiles, use movement while saying the word.

-

Contextual Learning: Don’t just learn words in isolation. Teach sight words within the context of reading sentences and stories. This helps children understand the meaning of the words and see how they function in real reading.

-

Engaging Activities and Games: Make learning fun and interactive:

- Sight Word Games: Bingo, matching games, word hunts, online sight word games.

- Flashcard Activities: “Snap,” “Go Fish,” sentence building with flashcards.

- Technology Integration: Utilize educational apps and websites that offer engaging sight word practice.

-

Consistent Review and Practice: Regular review is crucial for sight word mastery. Incorporate sight word practice into daily reading routines. Revisit previously learned words frequently to solidify recognition.

Learning to Read Should Be Empowering

The goal of teaching sight words isn’t to create frustration or make reading feel like a chore. The aim is to empower children with the skills and confidence to become lifelong readers. By understanding the science of reading and employing effective, phonics-based strategies, you can guide children on a more joyful and successful path to literacy.

If you’ve been using rote memorization, there’s no need for discouragement. Shifting to a more balanced approach that emphasizes decoding and strategic teaching of “tricky words” can make a significant difference in your child’s reading journey. Remember, building a strong foundation in phonics is the key to unlocking a world of words and fostering a genuine love for reading.

References:

- Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the brain: The new science of how we read. Penguin Books.

- Seidenberg, M. S. (2017). Language at the speed of sight: How we read, why so many can’t, and what we can do about it. Basic Books.

- Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. MIT Press.

- Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188.

Share this post to help other parents and educators discover effective sight word learning strategies!