For individuals navigating the complexities of modern life, Stoicism emerges as a practical philosophy, designed to cultivate resilience, enhance happiness, foster virtue, and promote wisdom. This ancient approach offers a pathway to becoming better individuals, parents, and professionals alike.

Throughout history, Stoicism has resonated with influential leaders across various fields. Kings, presidents, artists, writers, and entrepreneurs have all drawn inspiration from its principles. Figures such as Marcus Aurelius, Frederick the Great, Montaigne, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and General James Mattis represent just a fraction of those shaped by Stoic philosophy.

But what exactly is Stoicism? Who were the Stoics, and more importantly, How To Learn Stoicism Meaning and integrate it into your own life? This guide will delve into these questions and more, providing a comprehensive introduction to this transformative philosophy.

I. Unpacking Stoicism: What Does It Truly Mean?

“Of all people only those are at leisure who make time for philosophy, only they truly live. Not satisfied to merely keep good watch over their own days, they annex every age to their own. All the harvest of the past is added to their store.” — Seneca

Imagine discovering timeless wisdom preserved in the private journals of a Roman emperor, the personal letters of a renowned playwright and political strategist, and the lectures of a former slave turned influential teacher. These remarkable documents, surviving for two millennia, form the core of Stoicism—an ancient philosophy that once thrived as a leading civic discipline in the Western world. Stoicism was embraced across social strata, from the wealthy to the impoverished, the powerful to those struggling, all seeking a path to the Good Life.

However, in contemporary understanding, Stoicism is often either unknown or misinterpreted. For many, this dynamic, action-oriented philosophy has been reduced to simply meaning “emotionlessness.” The term “Stoic philosophy” might initially sound daunting, an abstract academic subject far removed from the urgent needs of daily life.

Yet, to equate Stoicism with mere emotional suppression is a profound mischaracterization. True Stoicism is a powerful toolkit for achieving self-mastery, cultivating perseverance, and attaining wisdom. It is a practical guide for living a fulfilling life, not an obscure intellectual pursuit. History’s luminaries recognized this intrinsic value. George Washington, Walt Whitman, Frederick the Great, Eugène Delacroix, Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Ralph Waldo Emerson are among the many who studied, quoted, and admired Stoic thinkers. The ancient Stoics themselves were figures of immense stature. Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor; Epictetus, a former slave who became a respected lecturer and advisor; and Seneca, a celebrated playwright and political counselor, are just a few of the pivotal figures whose writings and teachings form the bedrock of Stoicism.

What did these exceptional individuals find in Stoicism that remains largely overlooked today? They discovered a source of essential strength, profound wisdom, and enduring stamina—qualities indispensable for navigating life’s inevitable challenges. Understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning is about unlocking these very tools for your own life.

To deepen your understanding of Stoicism and learn how to apply its principles practically, consider exploring resources like “Stoicism 101: Ancient Philosophy For Your Actual Life.” Courses and books like these can provide structured pathways to integrate Stoic wisdom into your daily routines.

II. The Genesis of Stoicism: Tracing Its Origins

Stoicism’s story begins around 304 BC with Zeno of Citium, a merchant whose life took an unexpected turn. A shipwreck during a trading voyage resulted in the loss of nearly all his possessions. Finding himself in Athens, Zeno encountered the teachings of Cynic philosopher Crates and Megarian philosopher Stilpo, experiences that profoundly reshaped his life. Reflecting on this pivotal moment, Zeno later quipped, “I made a prosperous voyage when I suffered shipwreck.” He would eventually establish his school of thought at the Stoa Poikile, meaning “painted porch.” This porch, built in the 5th century BC, became the gathering place for Zeno and his followers. While initially called Zenonians, Zeno’s humility led to his philosophical school being named Stoicism, after the Stoa, rather than bearing his own name, a rarity among philosophical and religious movements. This origin story is crucial to understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning as it highlights the philosophy’s birth from adversity and its emphasis on resilience.

III. Key Figures in Stoicism: Learning from Stoic Philosophers

King Agasicles of Sparta once wisely stated his desire to be “the student of men whose son I should like to be as well.” This sentiment is crucial when seeking role models, and it applies perfectly to the study of Stoicism. Before delving into its precepts, it’s essential to consider: Who were the individuals who embodied these principles? Who serves as an example? Are these individuals worthy of admiration and emulation? Understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning involves studying the lives and teachings of key Stoic philosophers.

For those new to Stoicism, Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus are the three foundational figures to become acquainted with first. Their lives and writings offer profound insights and serve as compelling examples of Stoic principles in action.

Marcus Aurelius: The Emperor Philosopher

“Alone of the emperors,” wrote the historian Herodian about Marcus Aurelius, “he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life.” Cassius Dio echoed this sentiment: “In addition to possessing all the other virtues, he ruled better than any others who had ever been in any position of power.”

Born Marcus Catilius Severus Annius Verus on April 26th, 121, his path to becoming Emperor of the Roman Empire was far from predetermined. Emperor Hadrian, recognizing young Marcus’s potential through his academic achievements, took a keen interest in him. Hadrian, who enjoyed hunting with Marcus, affectionately nicknamed him Verissimus, “the truest one.” By Marcus’s 17th birthday, Hadrian began orchestrating an extraordinary plan.

Hadrian decided to make Marcus Aurelius the future emperor of Rome. On February 25th, 138, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius, a 51-year-old man, on the condition that Antoninus, in turn, adopt Marcus Aurelius. Hadrian envisioned Antoninus serving as a regent and mentor, anticipating a relatively short reign. However, Antoninus ruled for an impressive twenty-three years.

In 161, upon Antoninus’s death, Marcus Aurelius ascended to the throne, becoming Emperor of the Roman Empire. His nearly two-decade reign was marked by significant challenges: wars with the Parthian Empire, conflicts with barbarian tribes along the northern borders, the rise of Christianity, and a devastating plague that claimed millions of lives.

The historian Edward Gibbon described Marcus’s reign, the last of the ‘Five Good Emperors,’ as a period where “the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue.” This “guidance of wisdom and virtue” distinguishes Marcus from many leaders throughout history. His personal journal, Meditations, provides unparalleled insight into the mind of a powerful ruler constantly striving for virtue, justice, resilience, and wisdom.

For Marcus Aurelius, Stoicism was not merely an abstract philosophy but a practical framework for coping with the immense pressures of leading a vast empire. Studying his life and Meditations is a powerful step in how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to leadership and personal challenges.

Seneca: The Statesman and Playwright

Born in Corduba, Spain, around 4 BC, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, known as Seneca the Younger, was son to Seneca the Elder, a wealthy and learned writer. Seneca the Younger was destined for prominence from birth. His father chose Attalus the Stoic as his tutor, recognizing his reputation for eloquence. Seneca embraced his education with fervor, dedicating himself to learning and eagerly engaging with his studies. From Attalus, Seneca learned a crucial lesson: the purpose of philosophy is practical improvement in the real world. Philosophy, his teacher emphasized, should enable one to “take away with him some one good thing every day: he should return home a sounder man, or on the way to becoming sounder.”

While his commitment to self-improvement pleased his teachers, they were also aware of his father’s aspirations for him—a successful political career, not a life of philosophy. In Rome, a young lawyer could begin practicing as early as age 17, and Seneca indeed pursued this path. However, in his early twenties, a lung condition forced him to interrupt his burgeoning career. He spent nearly a decade in Egypt to recover, dedicating this time to writing, reading, and strengthening his health.

Seneca returned to Rome at age 35 in 31 AD, a period marked by political paranoia, violence, and corruption under Tiberius and Caligula. Seneca largely avoided the political spotlight during these perilous reigns. His life took a dramatic turn in 41 AD when Claudius became emperor and exiled Seneca to Corsica. This exile lasted eight years. Initially productive, writing Consolation to Polybius, Consolation to Helvia, and On Anger, Seneca soon found himself in need of consolation. It was during this time that he began his practice of letter writing, a practice he continued throughout his life, and which provides invaluable insights into how to learn Stoicism meaning through practical application.

Eight years later, Agrippina, mother of the future Emperor Nero and wife of Claudius, recalled Seneca from exile to tutor her son. At 53, Seneca was suddenly thrust into the heart of the Roman imperial court. Despite his efforts, Seneca had limited influence on Nero, who proved to be increasingly tyrannical. While his mission to guide Nero may have been ultimately unsuccessful, Seneca believed in the Stoic duty to engage in public life. He understood the difference between Stoics and Epicureans: Stoics saw political involvement as an obligation. Seneca’s life exemplifies the Stoic commitment to duty and engagement with the world, even in the face of adversity. His letters remain a cornerstone for anyone seeking how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to leadership, relationships, and personal ethics.

Epictetus: From Slavery to Sage

In contrast to Seneca, who often discussed the complexities of slave ownership from the perspective of the owner, Epictetus experienced slavery firsthand. Born into slavery, his given name is unknown; Epictetus is Greek for “acquired.” Interestingly, Epictetus’s mentions of his owner, Epaphroditus, are surprisingly neutral, despite historical accounts portraying Epaphroditus as exceptionally cruel, even by Roman standards. Later Christian writers recount tales of Epaphroditus’s brutality, including an incident where he twisted Epictetus’s leg with excessive force, perhaps as punishment, for amusement, or in a fit of rage. When the leg broke, Epictetus reportedly remained calm, without cries or tears, simply remarking to his master, “Didn’t I warn you?”

Epictetus lived with a limp for the rest of his life, yet he remained unbroken in spirit. He famously stated, “Lameness is an impediment to the leg, but not to the will.” Epictetus chose to view his physical limitation as merely that—physical. This emphasis on choice became central to his philosophical beliefs. He often compared life to a play, where individuals are assigned roles. Whether one is to play a poor man, a cripple, a governor, or a private citizen, the key is to “act it naturally.” For Epictetus, “this is your business, to act well the character assigned you; to choose it is another’s.”

Roman law under Augustus stipulated that slaves could not be freed before age 30. Epictetus gained his freedom shortly after Emperor Nero’s death. He dedicated himself fully to philosophy, teaching in Rome for approximately 25 years until Emperor Domitian banished all philosophers from the city. Epictetus relocated to Nicopolis in Greece, where he founded a philosophy school and taught until his death.

Epictetus’s life story is a powerful lesson in resilience and inner freedom. His teachings, preserved in Discourses and Enchiridion, emphasize the power of focusing on what we control—our thoughts and actions—and accepting what we do not. His example is vital for understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to overcoming adversity and finding inner peace.

IV. The Four Cardinal Virtues of Stoicism: Guiding Principles for Life

Stoicism centers around four cardinal virtues:

- Courage

- Temperance

- Justice

- Wisdom

Marcus Aurelius himself considered these virtues paramount, writing, “If, at some point in your life, you should come across anything better than justice, truth, self-control, courage—it must be an extraordinary thing indeed.” Millennia later, despite countless advancements, these virtues remain timeless and essential. Have we truly discovered anything more fundamental than bravery, moderation, righteousness, and understanding?

The answer, for Stoics, is no. Every situation in life presents an opportunity to embody these four virtues. Understanding these virtues is fundamental to how to learn Stoicism meaning.

Courage: Facing Challenges Head-On

In Cormac McCarthy’s novel All the Pretty Horses, Emilio Perez poses a crucial question to John Grady, one that encapsulates a core aspect of a meaningful life:

“The world wants to know if you have cojones. If you are brave?”

Stoics approach this concept of courage with a similar emphasis on facing adversity. Seneca famously pitied those who had never experienced misfortune, stating, “You have passed through life without an opponent. No one can ever know what you are capable of, not even you.”

Life, from a Stoic perspective, inevitably presents challenges to test our mettle. These difficulties are not mere inconveniences or tragedies but rather opportunities to demonstrate and cultivate courage. Do we possess inner fortitude? Will we confront problems or evade them? Will we stand firm or be overcome?

Our actions in the face of adversity define our character. Courage, for Stoics, is not reckless abandon but the strength to act rightly and resolutely in challenging circumstances. It is the foundational virtue that enables us to live authentically and purposefully. Learning how to learn Stoicism meaning begins with understanding the central role of courage.

Temperance: The Virtue of Moderation

Courage, while essential, is not the sole virtue. Unbridled bravery can devolve into recklessness, endangering oneself and others. This is where temperance, or moderation, becomes crucial.

Aristotle used courage as a prime example in his concept of the “Golden Mean.” He posited that virtues often lie between two extremes. In the case of courage, cowardice represents a deficiency, while recklessness signifies an excess. Temperance is the “golden mean”—the right measure.

Temperance, in Stoicism, is about acting with balance and restraint. It’s “doing nothing in excess,” finding “the right thing in the right amount in the right way.” As Aristotle also stated, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.” Virtue, therefore, is not a sporadic occurrence but a consistent way of living, an ingrained habit.

Epictetus further emphasized this, saying, “Capability is confirmed and grows in its corresponding actions, walking by walking, and running by running… therefore, if you want to do something, make a habit of it.” Excellence, success, and happiness are cultivated through daily habits and consistent practice, not through grand gestures or fleeting efforts.

This is encouraging news. Significant personal growth and achievement are attainable through small, consistent adjustments, effective systems, and well-chosen processes. Temperance, therefore, is about cultivating the habits that support virtuous living. Understanding temperance is key to how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to personal discipline and balanced living.

Justice: The Cornerstone of Virtue

Bravery and balance are vital Stoic virtues, but for Stoics, nothing surpasses the importance of justice—of doing what is right.

Justice is considered the most paramount Stoic virtue, influencing all others. Marcus Aurelius called it “the source of all the other virtues.” Throughout history, Stoics have championed justice, often at great personal cost, to defend principles and people they believed in.

- Cato the Younger sacrificed his life attempting to restore the Roman Republic.

- Thrasea Paetus and Helvidius Priscus resisted Nero’s tyranny, also paying with their lives.

- Inspired by Stoic ideals, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson led the formation of a new nation founded, albeit imperfectly, on principles of democracy and justice.

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a translator of Epictetus, commanded a regiment of Black troops in the US Civil War.

- Beatrice Webb, a founder of the London School of Economics and a pioneer of collective bargaining, regularly reread Marcus Aurelius.

Numerous activists and political figures have turned to Stoicism for strength and guidance in their fight for justice. Stoicism underscores the belief that individuals can effect meaningful change. Effective activism and political action require strategy, understanding, realism, and hope. They demand wisdom, acceptance, and a simultaneous refusal to accept injustice.

James Baldwin eloquently captured this tension in Notes of a Native Son:

It began to seem that one would have to hold in mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in light of this idea it goes without saying that injustice is commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but one must fight them with all one’s strength.

A Stoic possesses clarity of vision, seeing the world as it is while also envisioning what it could become. They are then courageous and strategic enough to work towards realizing that better world. Justice, in Stoicism, is not merely about legal correctness but about ethical action and striving for a more equitable and virtuous society. Grasping the concept of justice is vital to how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to ethical decision-making and social responsibility.

Wisdom: The Guiding Light

Courage, temperance, and justice are fundamental virtues, but discerning when to apply courage, what constitutes the right balance, and what is the just course of action requires wisdom. Wisdom is the discerning faculty, the knowledge, learning, and experience necessary to navigate life effectively.

Stoics have always highly valued wisdom. Zeno himself observed that we are given two ears and one mouth for a reason—to listen more than we speak. Similarly, with two eyes, we should observe and read more than we talk.

In today’s information-saturated world, distinguishing between mere data and genuine wisdom is crucial, just as it was in ancient times. Wisdom is the key to living a good life. It necessitates continuous learning and maintaining an open mind. Epictetus cautioned, “You cannot learn that which you think you already know.” Humility and a student’s mindset are prerequisites for acquiring wisdom.

Seeking out wise teachers and engaging in continuous reading are essential practices. Diligence in filtering signal from noise is equally important. The goal is not simply to accumulate information but to acquire the right information—the lessons found in Meditations, in Epictetus’s teachings, in the experiences of figures like James Stockdale, and in timeless philosophical texts.

Millennia of profound insights are available to us. We possess unprecedented access to knowledge. To honor the Stoic virtue of wisdom, we must cultivate deliberate slowness, thoughtful reflection, and a persistent quest for understanding.

Two eyes, two ears, one mouth: remain a student. Act accordingly—and wisely. Wisdom is the linchpin that integrates all other virtues, guiding their application. Understanding wisdom is the final piece in grasping how to learn Stoicism meaning and applying it to informed decision-making and insightful living.

V. Essential Stoic Texts: Books to Learn Stoicism Meaning

To truly understand how to learn Stoicism meaning, engaging with the primary texts of Stoicism is essential. Here are some of the most important books:

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius:

Meditations is a unique and invaluable document—the personal reflections of the most powerful man in the world offering guidance to himself on fulfilling his responsibilities and obligations. Marcus Aurelius engaged in nightly spiritual exercises, reminders to cultivate humility, patience, empathy, generosity, and resilience. Reading Meditations invariably provides insights and wisdom applicable to facing personal challenges. It is practical philosophy embodied.

Letters from a Stoic by Seneca:

While Marcus Aurelius primarily wrote for himself, Seneca readily offered counsel and support to others. As Nero’s tutor, he aimed to mitigate the emperor’s destructive impulses. Seneca’s letters offer timeless advice on grief, wealth, power, relationships, and life’s broader challenges. His insights are readily accessible and profoundly relevant. Letters from a Stoic is an excellent starting point, and his essays in On the Shortness of Life are equally valuable.

Discourses by Epictetus:

The survival of Epictetus’s teachings is a remarkable testament to their power. Thanks to his student Arrian, who meticulously transcribed Epictetus’s lectures, we have access to his profound insights. Arrian noted his dedication to capturing Epictetus’s words verbatim “as a record for later use of his thought and frank expression.” Arrian himself applied these lessons to achieve success as a political advisor, military commander, and author. Marcus Aurelius, in Meditations, acknowledges his debt to Epictetus, thanking his teacher Rusticus for introducing him to Epictetus’s lectures and lending him his personal copy.

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman:

The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living offers a structured approach to Stoic wisdom, featuring daily readings with new translations of key passages from Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, Epictetus, and lesser-known Stoics. Each day provides a Stoic insight and practical exercise, guiding readers on a year-long journey towards serenity, self-awareness, and resilience.

The Obstacle Is the Way by Ryan Holiday:

Inspired by Stoicism and Marcus Aurelius’s maxim, “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way,” The Obstacle Is The Way explores core Stoic principles for thriving under pressure. Through historical examples, the book demonstrates how to overcome adversity, transform obstacles into opportunities, and embrace fate. It has become a popular guide for athletes, coaches, and anyone seeking to build resilience.

VI. Practical Stoic Exercises: How to Be a Stoic in Daily Life

Understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning is not just about intellectual comprehension; it’s about practical application. Here are nine Stoic exercises to begin integrating Stoicism into your daily life:

1. The Dichotomy of Control: Focus on What You Can Influence

“The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control. Where then do I look for good and evil? Not to uncontrollable externals, but within myself to the choices that are my own . . .” – Epictetus

The most fundamental Stoic practice is distinguishing between what we can control and what we cannot. We have influence over our thoughts, judgments, and actions, but external events, other people’s opinions, and the past are beyond our direct control. Yelling at an airline representative won’t stop a storm-induced flight delay. Wishing won’t change your height or birthplace. Focusing energy on uncontrollable factors is not only futile but also detracts from what we can change—our responses and choices.

Daily, especially in challenging situations, ask yourself: What is within my control here? What is not? Journaling and reflecting on this dichotomy can shift your focus to effective action and inner peace. By concentrating on your sphere of influence, you gain a significant advantage over those who waste energy battling the uncontrollable.

2. Journaling: Reflecting for Self-Improvement

“Few care now about the marches and countermarches of the Roman commanders. What the centuries have clung to is a notebook of thoughts by a man whose real life was largely unknown who put down in the midnight dimness not the events of the day or the plans of the morrow, but something of far more permanent interest, the ideals and aspirations that a rare spirit lived by.” – Brand Blanshard

Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, and Seneca, despite their vastly different lives, shared a practice: journaling. Epictetus advised his students to “write down day by day” philosophical reflections, considering writing as a form of “spiritual exercise.” Seneca preferred evening journaling, reviewing his day, examining his actions and words, “hiding nothing from myself, passing nothing by.” Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations are themselves a form of personal journaling, “to himself.”

In Stoicism, journaling is more than a diary; it’s a core practice of the philosophy itself. It’s about preparing for the day, reflecting on the past day, and reinforcing learned wisdom from teachers, readings, and experiences. Lessons need repetition and internalization, achieved by writing them down, engaging with them actively.

Stoicism is designed as a routine practice, not a philosophy to be passively read and instantly grasped. It’s a lifelong pursuit requiring diligence, repetition, and focus—what Pierre Hadot called “spiritual exercising.” Daily journaling helps embed Stoic principles into your daily life, making them readily accessible and deeply understood.

Journaling is integral to how to learn Stoicism meaning. It’s a practical tool for self-reflection, application, and continuous learning.

3. Practice Misfortune: Preparing for Setbacks

“It is in times of security that the spirit should be preparing itself for difficult times; while fortune is bestowing favors on it is then is the time for it to be strengthened against her rebuffs.” – Seneca

Seneca advocated for periodically practicing poverty. He suggested setting aside days each month to experience want—eating simple food, wearing modest clothes, leaving behind comfort. By confronting hardship voluntarily, you can diminish its power over you. Ask yourself, “Is this what I used to dread?”

This exercise is not theoretical but experiential. Comfort can become a form of enslavement, breeding fear of loss. By practicing misfortune, you desensitize yourself to potential disruptions.

Anxiety and fear often stem from uncertainty, not actual experience. Familiarize yourself with your fears, the worst-case scenarios. Practice them mentally or in reality. The potential downsides are usually temporary and reversible. By rehearsing misfortune, you lessen its power to unsettle you. This practice enhances your resilience and clarifies how to learn Stoicism meaning in the face of adversity.

4. Train Your Perceptions: Transforming Obstacles

“Choose not to be harmed and you won’t feel harmed. Don’t feel harmed and you haven’t been.” – Marcus Aurelius

Stoics practiced “Turning the Obstacle Upside Down,” aiming to make philosophical practice constant. By reframing problems, every “bad” situation becomes a source of potential good.

If someone responds negatively to your help, instead of frustration, see it as an opportunity to cultivate patience or understanding. A loss becomes a chance to demonstrate fortitude. Marcus Aurelius famously said, “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

Like Obama’s “teachable moments,” Stoics seek to transform negative situations into opportunities for growth and learning. Entrepreneurs are known for creating opportunities; Stoics see opportunity in everything. A frustrating interaction, a loss—these are obstacles, but Stoicism teaches us to transform them into opportunities for virtue and growth.

Stoicism emphasizes that there is no inherent good or bad, only perception. You control your perceptions. Challenge your initial reactions. Disconnect your first impression from emotional escalation. Everything, then, becomes simply an opportunity for practice and growth. This exercise is central to how to learn Stoicism meaning and apply it to perspective and resilience.

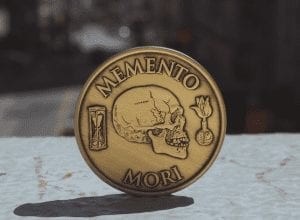

5. Remember Impermanence: Memento Mori

“Alexander the Great and his mule driver both died and the same thing happened to both.” – Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius frequently reminded himself of impermanence to maintain perspective and balance:

“Run down the list of those who felt intense anger at something: the most famous, the most unfortunate, the most hated, the most whatever: Where is all that now? Smoke, dust, legend…or not even a legend. Think of all the examples. And how trivial the things we want so passionately are.”

The Stoics sought to replace unhealthy “passions” (irrational, excessive desires and emotions like anger) with healthy “eupatheiai” (like joy instead of excessive pleasure). This exercise centers on remembering your own smallness in the grand scheme of things, and the fleeting nature of achievements.

Remember how small you are, how ephemeral most things are. Achievements are temporary. Possession is fleeting. If everything is impermanent, what truly matters? The present moment matters. Being a good person, acting virtuously now—this is what Stoics valued.

Consider Alexander the Great. He conquered vast empires, but also, in a drunken rage, killed his friend Cleitus, plunging into deep despair. Is this a hallmark of a successful life? Personal legacy means little if you lose perspective and harm those around you.

Learn from Alexander’s mistake. Cultivate humility, honesty, and awareness. These are enduring qualities you can possess daily, impervious to external loss or internal corruption. Memento Mori, remembering death, is a powerful tool in how to learn Stoicism meaning and live a virtuous, present-focused life.

6. The View From Above: Gaining Perspective

“How beautifully Plato put it. Whenever you want to talk about people, it’s best to take a bird’s- eye view and see everything all at once— of gatherings, armies, farms, weddings and divorces, births and deaths, noisy courtrooms or silent spaces, every foreign people, holidays, memorials, markets— all blended together and arranged in a pairing of opposites.” – Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius practiced “taking the view from above,” or “Plato’s view.” This exercise involves mentally stepping back to see life from a broader perspective, beyond immediate concerns. Envisioning millions of people, “armies, farms, weddings and divorces, births and deaths,” helps diminish the perceived importance of your individual worries and reinforces your relative insignificance in the vastness of existence.

This exercise reorients your value judgments. Luxury, power, war, and daily anxieties appear less significant from this expansive viewpoint, as Stoic scholar Pierre Hadot noted.

Beyond diminishing self-importance, this exercise taps into sympatheia, the Stoic concept of mutual interdependence with humanity. Astronaut Edgar Mitchell described experiencing a “global consciousness” and “people orientation” from space. Taking the view from above encourages you to transcend personal concerns and recognize your duty to the broader human community. This exercise provides crucial perspective for understanding how to learn Stoicism meaning and applying it to your role in the world.

7. Meditate on Mortality: Memento Mori

“Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life’s books each day. … The one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time.” – Seneca

Memento Mori, meditating on mortality, is an ancient practice dating back to Socrates, who considered philosophy “about nothing else but dying and being dead.” Marcus Aurelius urged, “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” This is a reminder to live virtuously now, not later.

Meditating on mortality is not morbid but invigorating and humbling. Seneca’s biography is titled Dying Every Day. Seneca advised reminding ourselves at bedtime, “You may not wake up tomorrow,” and upon waking, “You may not sleep again,” as reminders of life’s fragility. Epictetus urged students to “Keep death and exile before your eyes each day… by doing so, you’ll never have a base thought nor will you have excessive desire.”

Use these reminders daily. Meditate on mortality to live more fully, appreciate each moment, and avoid wasting time. Memento Mori is a central practice in how to learn Stoicism meaning and live a meaningful, virtuous life.

8. Premeditatio Malorum: Preparing for Adversity

“What is quite unlooked for is more crushing in its effect, and unexpectedness adds to the weight of a disaster. This is a reason for ensuring that nothing ever takes us by surprise. We should project our thoughts ahead of us at every turn and have in mind every possible eventuality instead of only the usual course of events… Rehearse them in your mind: exile, torture, war, shipwreck. All the terms of our human lot should be before our eyes.” – Seneca

Premeditatio Malorum, “pre-meditation of evils,” is a Stoic exercise of imagining potential misfortunes—things that could go wrong or be taken away. It prepares us for life’s inevitable setbacks. Life is not always fair or predictable. We must psychologically prepare for difficulties. This is a powerful tool for building resilience and strength.

Seneca would rehearse his plans, anticipating potential disruptions. Planning a trip, he would consider storms, illness, or pirate attacks. “Nothing happens to the wise man against his expectation,” he wrote. Wise individuals anticipate potential obstacles and incorporate them into their plans.

By practicing Premeditatio Malorum, you become prepared for disruption, integrating potential setbacks into your approach. You become adaptable to both success and failure. This exercise is crucial for how to learn Stoicism meaning and develop mental resilience.

9. Amor Fati: Love of Fate

“To love only what happens, what was destined. No greater harmony.” – Marcus Aurelius

Nietzsche described his formula for human greatness as amor fati—love of fate: “That one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backwards, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it….but love it.”

Stoics embraced this attitude. Marcus Aurelius wrote, “A blazing fire makes flame and brightness out of everything that is thrown into it.” Epictetus echoed, “Do not seek for things to happen the way you want them to; rather, wish that what happens happen the way it happens: then you will be happy.”

Amor fati is a Stoic mindset for making the best of any situation. Embrace every moment, even challenges, as something to be welcomed, not avoided. Not just accept it, but love it, and grow stronger because of it. Like fire fueled by oxygen, obstacles become fuel for your potential. Amor fati is the ultimate expression of how to learn Stoicism meaning and live a life of acceptance, resilience, and purpose.

VII. Stoic Quotes for Daily Reflection

For more Stoic quotes, explore online resources and social media dedicated to Stoicism.

“We are often more frightened than hurt; and we suffer more from imagination than from reality.” — Seneca

“It’s silly to try to escape other people’s faults. They are inescapable. Just try to escape your own.” — Marcus Aurelius

“Our life is what our thoughts make it.” — Marcus Aurelius

“Don’t explain your philosophy. Embody it.” Epictetus

“If anyone tells you that a certain person speaks ill— of you, do not make excuses about what is said of you but answer, ‘He was ignorant of my other faults, else he would not have mentioned these alone.’” — Epictetus

“If it is not right, do not do it, if it is not true, do not say it.” — Marcus Aurelius

“You become what you give your attention to…If you yourself don’t choose what thoughts and images you expose yourself to, someone else will.” — Epictetus

“Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.” — Marcus Aurelius

“You always own the option of having no opinion. There is never any need to get worked up or to trouble your soul about things you can’t control. These things are not asking to be judged by you. Leave them alone.” — Marcus Aurelius

“All you need are these: certainty of judgment in the present moment; action for the common good in the present moment; and an attitude of gratitude in the present moment for anything that comes your way.” — Marcus Aurelius

“No person has the power to have everything they want, but it is in their power not to want what they don’t have, and to cheerfully put to good use what they do have.” — Seneca

“If anyone can refute me—show me I’m making a mistake or looking at things from the wrong perspective—I’ll gladly change. It’s the truth I’m after, and the truth never harmed anyone.” — Marcus Aurelius

“Today I escaped anxiety. Or no, I discarded it, because it was within me, in my own perceptions not outside.” — Marcus Aurelius

“You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realise this, and you will find strength.” — Marcus Aurelius

“It isn’t events themselves that disturb people, but only their judgements about them.” — Epictetus

“To be like the rock that the waves keep crashing over. It stands unmoved and the raging of the sea falls still around it.” — Marcus Aurelius

“First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do.” — Epictetus

“Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be One.” — Marcus Aurelius

“The primary indication of a well-ordered mind is a man’s ability to remain in one place and linger in his own company.” — Seneca

“Receive without pride, let go without attachment.” — Marcus Aurelius

VIII. Physical Reminders of Stoic Principles

Consider incorporating physical objects as tangible reminders of Stoic principles in your daily life:

Memento Mori Medallion:

The memento mori medallion serves as a constant reminder of mortality. The front depicts symbols of life (tulip), death (skull), and time (hourglass). The back features Marcus Aurelius’s quote: “You could leave life right now.”

Amor Fati Medallion:

The amor fati medallion embodies the love of fate mindset. The flame symbolizes Marcus Aurelius’s wisdom: “a blazing fire makes flame and brightness out of everything that is thrown into it.” The back includes Nietzsche’s quote on embracing and loving necessity.

Daily Stoic Challenge Deck:

The Daily Stoic Challenge Deck offers 30 challenge cards, each with instructions, a Stoic quote, and an illustration, providing year-round prompts for self-improvement.

P.S.

To further your Stoic journey, sign up for resources like the Daily Stoic newsletter to receive a free “Stoic Starter Pack,” including exercises, book recommendations, and excerpts from works like Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is The Way.

P.S.S.

For advanced Stoic learning, explore glossaries of Stoic terms, recommended reading lists, and interviews with Stoic scholars and practitioners.