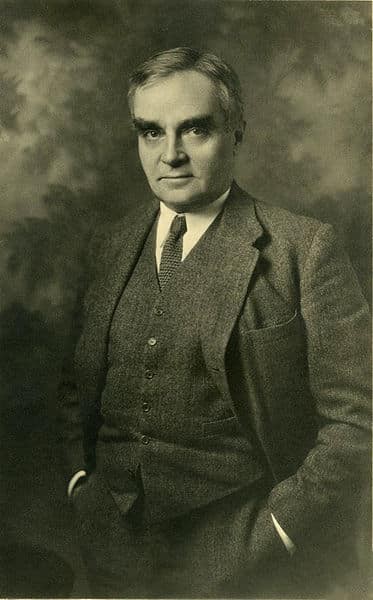

Billings Learned Hand (1872–1961) stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of American law. For over half a century, he served as a federal judge, both at the district and appellate levels, wielding considerable influence on the interpretation of law within the United States, particularly concerning the First Amendment. Despite never reaching the Supreme Court, Judge Learned Hand garnered widespread respect and admiration. This acclaim stemmed not only from his impactful legal decisions and scholarly writings but also from his ability to engage a broader audience through features in prominent magazines like Life and Reader’s Digest. Legal luminaries, including Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., recognized and lauded his exceptional legal acumen and eloquent prose.

From Albany to the Federal Bench: The Early Career of Judge Learned Hand

Following his graduation from Harvard Law School in 1896, Hand returned to his roots in Albany, New York. He began his legal career with a small local law firm before relocating to the bustling legal scene of New York City. However, the world of private practice left him unfulfilled. Seeking a different path, he became active in the local Republican Party, a strategic move aimed at securing a federal judgeship. His ambition bore fruit in 1909 when President William Howard Taft appointed him as a federal district judge. Later, in 1927, his career ascended further with an appointment to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Throughout his distinguished career, Judge Learned Hand was considered twice for a Supreme Court seat, a testament to his esteemed position within the legal community.

Landmark First Amendment Rulings by Judge Learned Hand

Judge Learned Hand’s impact on First Amendment jurisprudence is undeniable, marked by several key rulings. One of his most significant opinions as a district judge came in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917). In this case, he ruled against the New York City postmaster, asserting that employing the Espionage Act of 1917 to suppress political dissent was a violation of the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. Although this particular opinion was later reversed, it showcased Hand’s early commitment to free speech principles.

Further solidifying his influence on censorship law, Judge Learned Hand, while serving on the federal court of appeals in 1934, delivered another landmark decision. He declared that James Joyce’s groundbreaking novel Ulysses was not obscene and therefore could be legally published in the United States. This Ulysses decision became a pivotal precedent, shaping the landscape of censorship law and paving the way for greater freedom of expression in literature.

Judge Learned Hand and the Smith Act: Balancing Security and Liberty

Perhaps Judge Learned Hand‘s most renowned ruling as an appeals judge emerged in United States v. Dennis (2d Cir. 1950). This case, later affirmed by the Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States (1951), upheld the convictions of Eugene Dennis and other leaders of the Communist Party of the United States under the Smith Act of 1940. The Smith Act, a controversial piece of legislation, criminalized advocating the violent overthrow of the government.

In his ruling, Judge Learned Hand affirmed the Smith Act as a legitimate exercise of congressional power. While some critics argued that he gave insufficient weight to the clear and present danger test in this decision, Hand articulated a nuanced perspective. He posited that the application of the test involved weighing the “gravity of the evil, discounted by its improbability.” He argued that such balancing was inherently “a choice between conflicting interests,” a choice generally better suited for legislative bodies. He suggested judicial intervention should be reserved for instances where Congress delegates such choices to the courts, thereby framing these decisions as matters of law. In essence, Hand’s approach in Dennis underscored his belief in judicial restraint, even in cases involving fundamental freedoms.

Judicial Restraint: Judge Learned Hand’s Divergence from the Warren Court

Judge Learned Hand‘s commitment to judicial restraint often placed him at odds with the Supreme Court, particularly during the era of Chief Justice Earl Warren, known for its expansion of individual rights. In his influential Holmes lecture series at Harvard, culminating in “The Guardians” (1958), Hand articulated his reservations about the Warren Court’s doctrine of “preferred position” for certain individual freedoms, such as the First Amendment’s protections of religion and press.

While acknowledging the compelling arguments for affording heightened protection to freedom of speech, given potential majority hostility towards dissenting minorities, Judge Learned Hand maintained his conviction in judicial restraint. He believed that legislatures, rather than courts, were more likely to infringe upon these freedoms, thus highlighting the crucial role of judicial review as a safeguard against governmental overreach in protecting minority rights.

Despite his advocacy for judicial restraint, Judge Learned Hand was a staunch defender of constitutional protections. In “A Plea for the Open Mind and Free Discussion” (1959), he passionately advocated for reasoned responses to perceived threats. He famously stated, “Risk for risk, for myself I had rather take my chance that some traitors will escape detection than spread . . . a spirit of general suspicion and distrust. . . .The mutual confidence on which all else depends can be maintained only by an open mind and a brave reliance upon free discussion.” This quote encapsulates Judge Learned Hand‘s enduring belief in the paramount importance of open discourse and intellectual freedom for a healthy society.

Originally published in 2009, this article features content by Tobias T. Gibson, John Langton Professor of Legal Studies and Political Science at Westminster College in Fulton, MO.