Thirty years ago, as a college freshman, I found myself in Dr. Vereen Bell’s Modern American Novel course at Vanderbilt. Each week, I dedicated countless hours in the library, striving to keep up with my peers. While some classmates seemed effortlessly prepared for college life, equipped with backgrounds from well-resourced high schools, my public education in Alabama felt comparatively lacking. Despite being valedictorian, my high school achievements now felt insufficient. College demanded a different kind of preparedness, and I quickly realized that academic success here would require relentless effort and a willingness to Learn To Write effectively.

Early in the semester, facing the challenge of navigating demanding coursework, I immersed myself in studies and sought camaraderie with equally dedicated students. The reality of college-level writing hit hard when Dr. Bell returned our first paper, an analysis of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

His course was structured around weekly readings of literary classics, from Native Son to The Great Gatsby, each accompanied by the option to submit a two-page essay. Our final grade hinged on an average of our best six essays, alongside weekly quizzes. This system presented a strategic choice: gamble on writing only six exceptional papers or adopt a safer approach by writing an essay for each book, maximizing opportunities for a good grade.

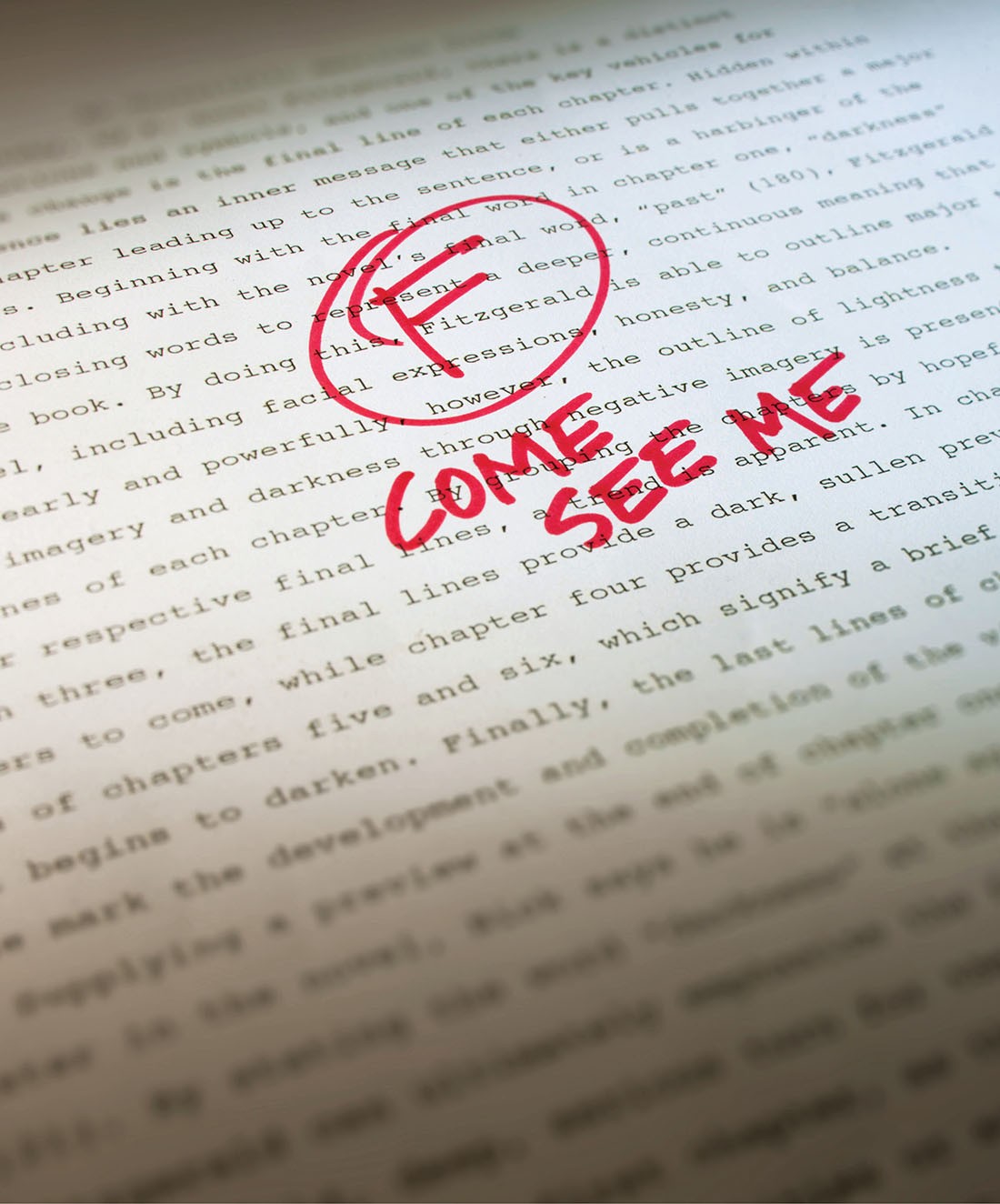

Dr. Bell, with his signature spectacles and tweed jacket, possessed a memorable classroom presence. Distributing our graded papers, he’d call out names and neatly fold each paper in half, concealing both the grade and his personalized comments. When he called my name, the single question staring back at me felt like an immediate indictment: “Where did you learn to write like this? Come see me.”

Beneath this stark question was an even starker letter: F.

The sting of that failing grade was physical. My face flushed, and I struggled to catch my breath. Paper in hand, I retreated from the classroom, attempting to regain composure as I walked back to the freshman dorm.

Back in the privacy of my dorm room, I kept the F grade to myself, wrestling with the initial shock.

Driven by a mix of fear of failure and a strong desire to improve, I scheduled a meeting with Dr. Bell. His office, a spacious room filled with light from large windows, felt like a sanctuary on campus.

During our meeting, the specifics of essay structure were lost in my anxiety, but his core message was clear and transformative. He offered a lifeline: if I committed to writing an essay for every novel and brought each draft to him before the deadline, he would provide feedback for revision. This was my opportunity to learn to write through direct, personalized guidance.

I seized this chance. Diligently, I wrote and revised every essay, fueled by Dr. Bell’s feedback. My IBM Selectric typewriter became my constant companion, Wite-Out always at hand for corrections. This intensive process revealed the true power of revision. By semester’s end, focusing on improvement and incorporating feedback, my final grade in the class was an A-.

Professor's feedback on student paper with a failing grade and the question 'Where did you learn to write like this? Come see me?' highlighting the importance of learning to write and seeking feedback.

Professor's feedback on student paper with a failing grade and the question 'Where did you learn to write like this? Come see me?' highlighting the importance of learning to write and seeking feedback.

Where did I learn to write? It wasn’t in a single semester, but I began to learn to write by learning to ask for help. This experience instilled in me a lasting appreciation for feedback. Throughout college, I consistently sought early reviews of my papers, revising them meticulously – driven by a desire for excellence and perhaps, a lingering insecurity. This process of seeking critique became integral to my writing development.

Dr. Bell’s legacy at Vanderbilt extends beyond my personal experience. Having taught for over 50 years, he championed diversity and actively participated in the Civil Rights movement in Nashville. A colleague described him as “a brilliant and caring teacher… a witty and refreshingly naughty presence.”

While I can’t attest to the “naughty” aspect, as a college professor myself today, I hesitate to use Dr. Bell’s direct approach of writing “Where did you learn to write like this?” on a student’s paper. Concerns about parental reactions and student evaluations make such directness daunting. However, Dr. Bell’s core lesson endures in my teaching. I encourage students to meet with me, submit drafts early, and utilize writing center resources. My office may not mirror his in grandeur, but the essence of that formative meeting 30 years ago remains present.

“Come see me,” I often write on student papers. It’s an invitation to collaborate on improving their writing, echoing Dr. Bell’s mentorship and reinforcing the enduring lesson: we learn to write best when we learn to revise and seek guidance together.

Yours truly,

Mallory

Mallory McDuff, BS’88, is a professor of environmental studies and outdoor leadership at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina. Her essays and op-eds have been featured in USA Today and The Huffington Post. Find out more at mallorymcduff.com.

Vereen Bell, professor of English, emeritus, retired in 2013 after 52 years of teaching at Vanderbilt.