Our brains are incredibly complex, constantly processing a massive amount of information every second. As you read this text, your brain is not only decoding words but also absorbing visual cues, sounds, and bodily sensations, managing everything from your breathing to your energy levels. Scientists estimate that our brains take in about 11 million bits of information per second, yet we’re only consciously aware of around 50 bits. This means a staggering amount of processing happens outside of our conscious awareness. To manage this overwhelming influx, our brains become highly efficient, automating routine tasks and decisions.

Think about driving a car. Initially, it requires intense focus – remembering to check mirrors, adjust seats, fasten seatbelts, and coordinate pedals. However, with practice, these actions become automatic, performed almost without conscious thought. This shift from conscious effort to unconscious habit is a fundamental way our brains operate, allowing us to navigate the complexities of daily life.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, in his renowned book Thinking, Fast and Slow, explains this through the concept of two systems of thinking. System 1 is rapid, automatic, and unconscious. It’s the system that instantly answers “what is 2 + 2?”. System 2, on the other hand, is slow, deliberate, and conscious – the system you’d engage to solve “what is 126 times 43?”. Kahneman suggests our brains prefer System 1 for its efficiency. Repetition reinforces this system, making tasks and even beliefs automatic and seemingly involuntary. This neurological efficiency, while often helpful, raises a critical question: what happens when the unconscious messages our brains absorb are ones we might not consciously endorse, particularly when it comes to biases about race and other social groups? This module delves into how we learn implicit biases, their impact, and what we can do about them.

Implicit biases are attitudes or stereotypes that operate at an unconscious level, influencing our actions, decisions, and perceptions without our awareness. Crucially, everyone possesses implicit biases. These biases can be either favorable or unfavorable, representing preferences for or aversions to certain things or groups. It’s important to distinguish implicit biases from explicit biases, which are conscious and openly expressed beliefs. In fact, implicit biases can often contradict a person’s consciously held values and beliefs.

The Formation of Implicit Bias: A Lifelong Learning Process

Implicit biases are not innate; they are learned over a lifetime, primarily through exposure to direct and indirect messages from our environment. The media plays a powerful role in shaping these unconscious attitudes. From news portrayals to entertainment narratives, media often reinforces stereotypes and societal biases, contributing to the formation of implicit biases. These messages are absorbed by our System 1 thinking, becoming ingrained associations in our minds.

1. Repeated Exposure and System 1 Thinking:

As Kahneman’s work suggests, repeated exposure to information, regardless of its accuracy or fairness, can lead to automaticity through System 1 thinking. When we consistently see certain groups portrayed in specific ways – for example, if media frequently depicts certain racial groups in association with crime – these associations can become embedded in our unconscious. This doesn’t require conscious agreement with the stereotype, just repeated exposure for System 1 to learn and automate the association.

2. Social Learning Theory:

Social learning theory further explains how implicit biases are acquired. We learn by observing and imitating the attitudes and behaviors of others around us, particularly authority figures, peers, and media personalities. If we grow up in an environment where biased language or actions are common, even subtly, we are likely to internalize these biases unconsciously. Children, especially, are highly susceptible to absorbing implicit biases from their families, communities, and the broader culture.

3. Cultural Narratives and Stereotypes:

Societies often have deeply ingrained cultural narratives and stereotypes about different groups. These narratives are perpetuated through stories, jokes, historical accounts, and everyday language. Even seemingly innocuous stereotypes can contribute to implicit bias. For instance, if a culture consistently associates certain professions with specific genders or races, individuals may unconsciously develop biases linking those groups to those roles.

Examples of Implicit Bias Learning in Action:

- Media Representation: If news media disproportionately focuses on crime committed by individuals from specific racial groups, viewers may unconsciously associate those groups with criminality, even if statistically inaccurate. Similarly, limited or stereotypical representation in films and television programs can shape unconscious perceptions of different groups.

- Educational Settings: Textbooks and curricula that primarily highlight the achievements of certain groups while marginalizing or omitting others can contribute to implicit biases about the capabilities and importance of different groups.

- Family and Community: Children may learn implicit biases by observing the subtle attitudes and behaviors of their family members and community members. For example, if adults in a child’s life consistently express discomfort or avoidance around people from certain racial groups, the child may unconsciously internalize these biases.

The Pervasive Impact of Implicit Bias

Research has consistently demonstrated the pervasive and significant impact of implicit bias across various domains of life, particularly for marginalized communities. These unconscious biases can translate into real-world consequences in areas such as education, healthcare, employment, and the justice system.

Research Highlights:

- Education: Studies have shown that preschool teachers, even when not consciously biased, tend to monitor Black male students more closely for challenging behavior than children of other races and genders. This can lead to disproportionate discipline and lower expectations for Black male students from an early age. Furthermore, white teachers have been found to have lower expectations for Black students’ academic achievement compared to Black teachers evaluating the same students.

- Healthcare: Implicit bias in healthcare can lead to disparities in treatment. Research indicates that medical professionals may unconsciously underestimate the pain levels of Black patients compared to white patients, resulting in less adequate pain management for Black individuals.

- Employment: Numerous studies using resume audits have demonstrated that applicants with names perceived as Black or Latinx are significantly less likely to receive callbacks for job interviews compared to white applicants with identical qualifications. This highlights how implicit bias can create barriers to equal opportunity in the workplace.

- Criminal Justice: Research has revealed that people tend to perceive young Black men as larger and more physically threatening than white men of the same size. This perception can contribute to biased judgments in law enforcement and the justice system, potentially leading to disproportionate use of force against Black individuals.

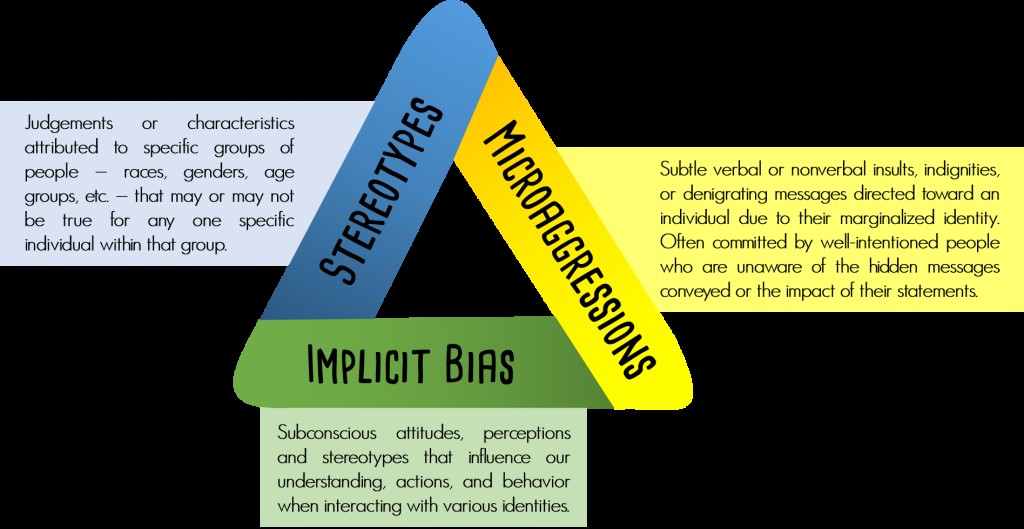

A triangle: the left side is blue with black text reading

A triangle: the left side is blue with black text reading

Microaggressions: Subtle Manifestations of Implicit Bias

One of the ways implicit biases manifest in interpersonal interactions is through microaggressions. Microaggressions are subtle, often unintentional, verbal or nonverbal behaviors that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to marginalized individuals. These can be based on race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or other aspects of identity.

Examples of racial microaggressions include:

- “Where are you really from?” (Implying someone is not a “true” member of their country of residence).

- “You’re so articulate” (Suggesting surprise at the intelligence of a person of color).

- “I don’t see color” (Denying the significance of a person’s racial identity).

While individual microaggressions may seem minor, their cumulative effect can be profound. For individuals from marginalized groups, experiencing microaggressions daily can create a constant sense of stress, exclusion, and devaluation. This chronic stress has been linked to negative health outcomes and can contribute to racial disparities in health and well-being.

Challenging and Changing Implicit Bias: Debiasing Strategies

While implicit biases are deeply ingrained, research suggests they are not immutable. Debiasing is possible and requires conscious effort, intention, and ongoing practice. Several strategies can be employed to challenge and reduce implicit biases:

1. Awareness and Education:

The first step in addressing implicit bias is recognizing its existence and understanding how it operates. Education about implicit bias, its origins, and its impact is crucial. Taking implicit bias tests, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT) developed by Project Implicit at Harvard, can help individuals become aware of their own unconscious biases.

2. Perspective-Taking and Empathy:

Actively trying to understand the perspectives and experiences of people from different groups can help challenge biased assumptions. Engaging in perspective-taking exercises and fostering empathy can weaken the hold of stereotypes and promote more inclusive attitudes.

3. Intergroup Contact:

Meaningful and positive contact with individuals from diverse groups can be a powerful tool for reducing implicit bias. Building genuine relationships across group lines can help break down stereotypes and foster a sense of common humanity. It is important that this contact is positive and occurs in contexts of equal status and shared goals.

4. Counter-Stereotypic Training and Imagery:

Consciously exposing oneself to counter-stereotypic examples and imagery can help reshape unconscious associations. This might involve actively seeking out media portrayals that challenge stereotypes, reading books and articles that highlight diverse perspectives, and consciously focusing on positive examples of individuals from groups about whom one holds biases.

5. Mindfulness and Deliberate Processing:

Practicing mindfulness and slowing down decision-making processes can help interrupt automatic, biased responses. By engaging System 2 thinking more deliberately, individuals can become more aware of their unconscious biases and make more conscious, equitable choices.

6. Institutional and Systemic Change:

Addressing implicit bias requires not only individual efforts but also systemic changes within institutions and organizations. Implementing policies and practices that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion can help mitigate the impact of implicit bias at a broader level. This might include diversity training programs, bias-reducing hiring practices, and equitable disciplinary procedures.

Conclusion: Towards a More Equitable Future

Understanding how we learn implicit bias is the first step towards dismantling its harmful effects. Implicit biases are not fixed traits but learned habits of mind that can be unlearned and replaced with more equitable and inclusive attitudes. By acknowledging the pervasive nature of implicit bias, educating ourselves and others, and actively engaging in debiasing strategies, we can work towards creating a more just and equitable society where unconscious biases no longer perpetuate inequality. This is an ongoing process, requiring sustained effort and commitment, but the potential for positive change is significant.

References

Gilliam, W. S., Maupin, A. N., Reyes, C. R., Accavitti, M., & Shic, F. (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions? Yale Child Study Center. Retrieved from https://medicine.yale.edu/childstudy/zigler/publications/Preschool%20Implicit%20Bias%20Policy%20Brief_final_9_26_276766_5379_v1.pdf.

Gershenson, S., Holt, S. B., & Papageorge, N. W. (2015). Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations. Upjohn Institute Working Paper 15-231. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(16), 4296-4301.

Markowsky, G. (n.d.). Information theory: Physiology. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/information-theory/Physiology.

Milkman, K. L., Akinola, M., & Chugh, D. (2012). Temporal distance and discrimination: An audit study in academia. Psychological Science 23(7), 710 – 717.

Okonofua, J. A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Sciences.

Pager, D., Bonikowski, B., & Western, B. (2009). Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: A field experiment. American Sociological Review 74(5), 777-799.

Smith, J. A. (2015). Why teachers are more likely to punish black students. Greater good: The science of a meaningful life. Retrieved from http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_teachers_are_more_likely_to_punish_black_students?utm_source=GGSC+Newsletter+-+May+2015&utm_campaign=GG+Newsletter+-+May+2015&utm_medium=email.

Wilson, J. P, Hugenberg, K., & Rule, N. O. (2017). Racial bias in judgments of physical size and formidability: From size to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113(1), 59 – 80.