Substance use disorders (SUDs) are complex conditions where individuals struggle to control their intake of drugs, despite harmful consequences. A crucial aspect of addiction lies in Learned Behavior. This refers to actions and responses that are acquired through experience, particularly through processes like Pavlovian and instrumental conditioning. Understanding how these learning mechanisms contribute to addiction is vital for developing effective treatments and prevention strategies.

This article delves into the role of learned behavior in SUDs, focusing on how environmental cues and habit formation can drive drug seeking and consumption. We will explore two key mechanisms: Pavlovian influences on drug intake, especially through Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer (PIT), and the shift from goal-directed to habitual drug use. By examining these processes, we aim to shed light on the underlying factors that contribute to the compulsive nature of addiction.

Pavlovian Learned Behaviors and Cue-Induced Drug Seeking

Drug addiction is significantly influenced by environmental cues associated with drug use. These cues can range from the sight and smell of drugs themselves to the settings and social contexts where drug use typically occurs. Pavlovian conditioning, a fundamental form of learned behavior, plays a critical role in how these cues gain power over an individual’s actions.

Cue-Induced Craving: A Pavlovian Response

In classical Pavlovian conditioning, a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a biologically significant event, like receiving food. Similarly, in addiction, neutral cues present during drug use become associated with the rewarding effects of the drug. Over time, these cues alone can trigger conditioned responses, most notably craving.

For example, someone who frequently drinks alcohol in a specific bar might begin to experience cravings simply by walking past that bar or seeing similar settings. These cues, initially neutral, have become powerful predictors of drug availability and the associated reward. This learned behavior of cue-induced craving is a major factor in relapse, as encountering these cues can trigger intense urges to use drugs even after periods of abstinence.

Pavlovian-to-Instrumental Transfer (PIT): How Cues Influence Action

While cue-induced craving is a significant Pavlovian response, the influence of learned cues extends beyond just triggering urges. Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer (PIT) describes how Pavlovian cues can energize and direct instrumental behaviors – actions taken to achieve a specific goal. In the context of addiction, PIT explains how drug-associated cues can motivate and guide drug-seeking behavior.

Imagine a scenario where an individual has learned that a certain sound (Pavlovian cue) is associated with receiving a monetary reward. Separately, they have learned to press a button (instrumental action) to also receive a reward. PIT occurs when presenting the sound cue increases the likelihood of button pressing, even though the cue itself doesn’t directly cause the reward in the button-pressing task.

In addiction, drug-related cues (Pavlovian stimuli) can similarly enhance drug-seeking actions (instrumental behaviors). The sight of drug paraphernalia, the smell of smoke, or even social contexts associated with drug use can act as Pavlovian cues, increasing the motivation and likelihood of engaging in drug-seeking behaviors. This learned behavior through PIT can make resisting drug use incredibly challenging, as environmental triggers can powerfully activate drug-seeking tendencies.

Neurobiological Basis of PIT: Brain Regions Involved

The influence of Pavlovian cues on instrumental behavior in addiction is mediated by specific brain regions. Research indicates that the amygdala, particularly the basolateral amygdala, plays a crucial role in processing the emotional significance of cues. The nucleus accumbens shell, a key area in the brain’s reward system, is also involved in outcome-specific PIT, where cues specifically enhance actions associated with the same reward. The nucleus accumbens core and central nucleus of the amygdala are implicated in general PIT, where cues broadly increase motivation for any reward-seeking behavior.

These neurobiological pathways highlight how learned behavior in the form of cue-reward associations becomes deeply embedded in the brain. The activation of these brain circuits by drug-related cues can override rational decision-making and propel individuals towards drug seeking, even when they consciously desire to abstain.

PIT in Different Substance Use Disorders

The PIT effect is not limited to alcohol use disorder (AUD), which was a primary focus in some of the cited research. Studies have shown that PIT effects are present across various substance use disorders, including:

- Smoking: Tobacco-related cues have been shown to trigger PIT effects in smokers, increasing their urge to smoke.

- Cocaine Addiction: Cues associated with cocaine use can powerfully motivate cocaine-seeking behavior through Pavlovian processes.

- Other Drugs: While research is ongoing, evidence suggests that PIT mechanisms likely contribute to addiction to opioids and amphetamines as well.

The consistency of PIT effects across different substances underscores the generalizability of learned behavior mechanisms in driving addictive behaviors. Regardless of the specific drug, Pavlovian cues can become potent triggers for drug seeking and relapse.

Using PIT to Understand Relapse Vulnerability

Understanding PIT is crucial for predicting relapse vulnerability in individuals with SUDs. Studies have shown that stronger PIT effects, particularly general PIT, are observed in individuals with AUD who are more likely to relapse. This suggests that the degree to which drug cues energize general reward-seeking behavior can be an indicator of relapse risk.

Interestingly, research has also revealed that individuals who successfully maintain abstinence from alcohol may exhibit a different pattern of PIT response to alcohol cues. Instead of triggering approach behavior, these cues can evoke an inhibitory response, potentially acting as warning signals. This suggests that learned behavior can be modified, and individuals can learn to use drug cues to avoid, rather than approach, drug-related situations.

Conflict Between Pavlovian and Instrumental Control

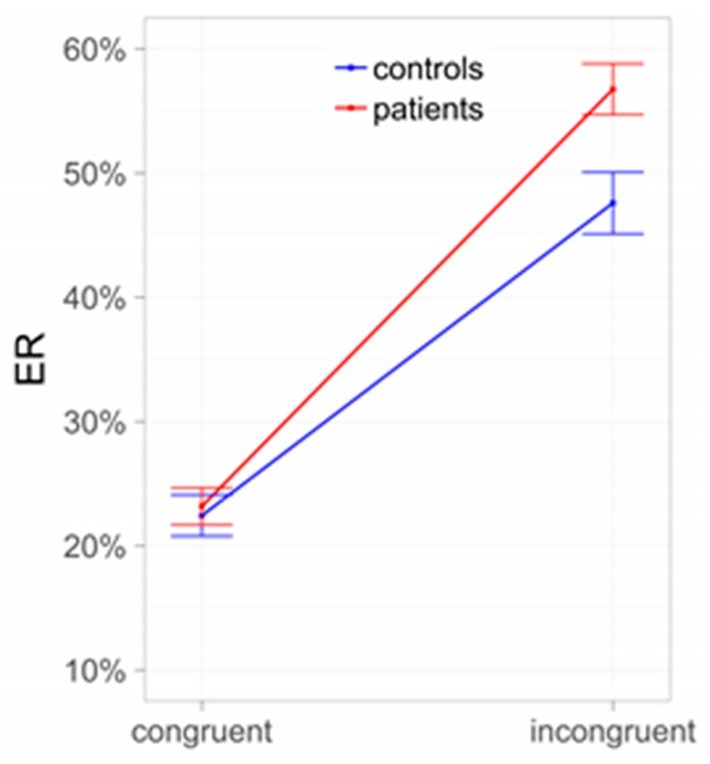

The interplay between Pavlovian and instrumental learning can create internal conflicts, especially in situations where learned cues signal danger or negative consequences while instrumental actions might still be driven by reward seeking. Research using tasks that create incongruence between Pavlovian and instrumental cues has shown that individuals with AUD exhibit greater error rates in these conflict situations. This suggests that impaired interference control, potentially stemming from weakened top-down cognitive control, can exacerbate the influence of Pavlovian cues on behavior, making it harder to resist drug-seeking urges.

Conflict between Pavlovian and instrumental control: Subjects with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared to controls. ER = error rates.

Conflict between Pavlovian and instrumental control: Subjects with alcohol use disorder (AUD) compared to controls. ER = error rates.

Alt text: Bar graph illustrating error rates in a conflict task comparing individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and healthy controls. The graph shows higher error rates in the incongruent condition for AUD subjects compared to controls, indicating a conflict between Pavlovian and instrumental control.

Habitual Learned Behaviors: The Shift from Goal-Directed to Automatic Drug Seeking

Beyond cue-driven responses, addiction is also characterized by a shift from goal-directed to habitual drug seeking. Initially, drug use might be a conscious, goal-directed behavior, motivated by the desire to experience pleasure or alleviate negative feelings. However, with repeated drug use, this behavior can become habitual, automatic, and less sensitive to its consequences. This transition from goal-directed to habitual control represents another critical aspect of learned behavior in addiction.

Dual-Process Theory and Habit Formation in Addiction

Dual-process theories of learning propose that behavior is controlled by two interacting systems: a goal-directed system and a habitual system. The goal-directed system is flexible and sensitive to outcomes, allowing individuals to adjust their actions based on changing goals and consequences. The habitual system, on the other hand, is rigid and automatic, driven by learned stimulus-response associations.

In addiction, the balance can shift towards the habitual system. Repeated drug use strengthens stimulus-response associations, so that drug-related cues automatically trigger drug-seeking habits, regardless of whether the individual still consciously desires the drug or is aware of the negative consequences. This learned behavior becomes ingrained and difficult to override.

Context and the Specificity of Habits in Addiction

While the concept of habit formation in addiction is well-established, recent research emphasizes the importance of context. Rather than a general shift towards habit-based behavior across all domains, addiction might involve the development of specific, context-dependent habits related to drug seeking and use.

For example, an individual might exhibit goal-directed behavior in most aspects of their life but display rigid, habitual drug-seeking behavior in specific drug-related contexts. This context-specificity suggests that interventions should target the specific cues and situations that trigger habitual drug use, rather than attempting to address a generalized deficit in goal-directed control.

Stress and the Strengthening of Habitual Drug Seeking

Stress is a significant factor in the development and maintenance of SUDs. Stress can impair executive functions and cognitive control, weakening the goal-directed system and strengthening the habitual system. Acute and chronic stress can both promote a shift towards habitual drug seeking, making it more difficult to resist drug urges and maintain abstinence.

Stress can also enhance stimulus-response learning, further solidifying drug-related habits. This interplay between stress and learned behavior underscores the importance of addressing stress management in addiction treatment.

Implications and Future Directions: Targeting Learned Behavior for Intervention

Understanding the role of learned behavior in addiction has significant implications for developing more effective interventions. By recognizing that drug seeking is driven by both cue-induced Pavlovian responses and habitual actions, treatment approaches can be tailored to target these specific learning mechanisms.

Personalized Interventions Based on Learning Mechanisms

Future treatments could utilize assessments of PIT and other measures of learned behavior to personalize interventions. For example, individuals with strong PIT responses to drug cues might benefit from targeted cue exposure therapy or interventions aimed at modifying cue-reactivity. Those exhibiting a strong reliance on habitual drug seeking might benefit from therapies that focus on strengthening goal-directed control and breaking automatic drug-use routines.

Technology and Computational Models for Real-World Assessment

Mobile technology, including smartphone apps and wearable sensors, offers exciting opportunities to assess learned behavior in real-world settings. Ecological momentary assessments (EMA) can capture real-time data on cue exposure, stress levels, mood states, and drug use behaviors. Computational models can be used to analyze this data and develop personalized risk profiles and intervention strategies.

By integrating real-world data with computational models of learning, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the dynamic interplay between cues, habits, and context in addiction. This knowledge can pave the way for more precise and effective interventions that target the specific learned behaviors driving individual addiction trajectories.

Conclusion: Reframing Addiction as a Disorder of Learned Behavior

Addiction is not simply a matter of willpower or moral failing, but a complex disorder deeply rooted in learned behavior. Pavlovian conditioning, particularly through PIT, creates powerful cue-induced urges and energizes drug-seeking actions. The shift from goal-directed to habitual drug use further solidifies addictive behaviors, making them automatic and resistant to change.

By understanding these learning mechanisms, we can move towards more targeted and effective interventions for SUDs. Future research should continue to explore the nuances of learned behavior in addiction, utilizing advanced technologies and computational models to develop personalized treatments that address the specific learning processes driving individual addiction and relapse vulnerability. Recognizing addiction as a disorder of learned behavior is crucial for fostering empathy, reducing stigma, and developing compassionate and scientifically grounded approaches to prevention and treatment.

References

[1] Wise, R.A. Dopamine reward pathways-role in addiction. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 2008, 17, 23–42.

[2] Wise, R.A. Brain reward circuitry: Linking circuit function to emotional states. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005, 15, 164–174.

[3] Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. Addiction. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 25–53.

[4] Schultz, W.; Dayan, P.; Montague, P.R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 1997, 275, 1593–1599.

[5] Treadway, M.T.; Buckholtz, J.W.; Cowan, R.L.; Woodward, N.D.; Li, R.; Ansari, M.S.; Bromberg, C.E.; Kessler, R.M. Dopaminergic mechanisms of individual differences in trait reward sensitivity. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3530–3537.

[6] Everitt, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Drug addiction: Updating actions to habits to compulsions ten years on. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 23–50.

[7] Koob, G.F.; Volkow, N.D. Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 760–773.

[8] Belin, D.; Jonkman, S.; Dickinson, A.; Robbins, T.W.; Dalley, J.W. Parallel and interactive learning processes within the basal ganglia: Relevance for the understanding of habit formation and goal-directed behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 2007, 179, 103–113.

[9] Robbins, T.W.; Gillan, D.; Smith, J.L.; de Wit, S. The Neurocognitive Basis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Insights from Animal Models. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 549–558.

[10] Grant, J.E.; Potenza, M.N.; Weinstein, A.; Gorelick, D.A.; Moeller, F.G.; Torre, J.B.; Verdejo-Garcia, A. Neurobiology of craving and relapse: Translating human imaging findings into clinical practice. Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 1392–1402.

[11] Voon, V.;构思et al. (List of co-authors missing from original text – please add full author list for accurate citation). Model-based and model-free decision-making and reward prediction errors in substance addictions. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 1579–1592.

[12] Dickinson, A. Instrumental conditioning. In Animal Learning and Cognition; Mackintosh, N.J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 45–79.

[13] Carter, R.M.; Tiffany, S.T. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 1999, 94, 327–340.

[14] Drummond, D.C.; Tiffany, S.T.; Glautier, S.; Remington, B. Addictive Behaviour: Cue Exposure Theory; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1995.

[15] Cartoni, E.; Balleine, B.W.; Dickinson, A. Instrumental control over interval timing. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. B 2003, 56, 275–298.

[16] Vollstädt-Klein, S.; Wichert, S.P.; Rabinstein, J.; Bühler, M.; Klein, O.; Ende, G.; Hermann, D.; Mann, K.; Kiefer, F. Prefrontal cortex activation after alcohol cue exposure is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Addict. Biol. 2011, 16, 612–621.

[17] Wrase, J.; Grüsser, S.M.; Klein, S.; Diener, C.; Hermann, D.; Flor, H.; Mann, K.; Braus, D.F. Development of alcohol-associated cues and cue-induced craving in abstinent alcoholics. Brain 2002, 125, 1751–1759.

[18] Heinz, A.; Beck, A.; Grüsser, S.M.; Grace, A.A.; Wrase, J.; Hermann, D.; Adams, R.; Reischies, F.M.; Kuhn, S.; Mössner, R.; et al. Dopamine transporter availability is reduced in detoxified patients with alcohol dependence: Correlation with impulsivity. Addict. Biol. 2004, 9, 103–109.

[19] Heinz, A.; Siessmeier, T.; Wrase, J.; Hermann, D.; Klein, S.; Grüsser, S.M.; Buchholz, H.G.; Rösch, F.; Smolka, M.N.; Köhler, T.; et al. Correlation between dopamine D(2) receptors in the ventral striatum and central processing of alcohol cues and craving. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1783–1789.

[20] Park, J.Y.; Sohn, J.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, B.O.; Jun, J.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; et al. Lower dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with greater medial prefrontal cortex activation by alcohol cues in alcohol use disorder. Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 162–172.

[21] Martinez, D.; Gil, R.; Slifstein, M.; Hwang, D.R.; Huang, Y.Y.; Perez, A.; Laruelle, M.; Evans, K.; Krystal, J.H.; Innis, R.B.; et al. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 779–786.

[22] Myrick, H.; Anton, R.F.; Li, X.; Henderson, S.; Randall, P.K.; Voronin, K.; George, M.S. Differential brain activity in alcoholics and social drinkers to alcohol cues: Relationship to craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 393–402.

[23] Domjan, M. The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 5th ed.; Thomson/Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2006.

[24] Holmes, P.J.; Everitt, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Placebo conditioning and drug expectancy in humans. Behav. Neurosci. 2004, 118, 139–147.

[25] Rescorla, R.A.; Solomon, R.L. Two-process learning theory: Relationships between Pavlovian conditioning and instrumental learning. Psychol. Rev. 1967, 74, 151–182.

[26] Balleine, B.W. Incentive processes in instrumental conditioning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 175–182.

[27] Tiffany, S.T. Cognitive concepts of craving. Alcohol. Res. Health 1999, 23, 215–224.

[28] Stewart, J. Reinstatement of heroin-seeking behavior in the rat by intracerebral application of morphine to the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1984, 322, 371–376.

[29] Dayan, P. Instrumental rationality and habit. Cogn. Brain Res. 2008, 28, 115–127.

[30] Schwabe, L.; Dalm, S.; Schächinger, H. Habitual control impairs the flexible adaptation of goal-directed behavior under stress. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 417–428.

[31] Sommer, M.; Sebold, M.; Spengler, S.; Smolka, M.N.; Wüst, S.; Heinz, A.; Bermpohl, F.; Schachtzabel, C. Personality traits modulate the effects of Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 1424–1432.

[32] Lovibond, P.F.; Mitchell, C.J.; Minard, E.; Davey, G.C.J. Evaluative conditioning and generalisation of conditioned valence. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1295–1309.

[33] Sinha, R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 61–79.

[34] Koob, G.F. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1149–1159.

[35] Quail, J.A.; Vogel, S.; Schwabe, L. Stress differentially affects stimulus-response and response-outcome learning in men and women. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 237.

[36] Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C.; Valenstein, E.P. Addiction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000.

[37] Loeber, S.; Duka, T.; Welzel, H.; Nakovics, H.; Heinz, A.; Flor, H.; Mann, K.; Sommer, C.; Vollstädt-Klein, S. Altered Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer in detoxified alcoholics predicts relapse. Addiction 2017, 112, 101–110.

[38] Loeber, S.; Mann, K.; Vollstädt-Klein, S. Avoidance of alcohol-associated cues and Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer in abstinent alcoholics: A possible mechanism for relapse prevention? Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 101–109.

[39] Corbit, L.H.; Janak, P.H. Neural substrates of pavlovian conditioned stimulus-potentiated feeding: Interactions between the central nucleus of the amygdala and nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 12189–12199.

[40] Holland, P.C.; Gallagher, M. Amygdala circuitry in attentional and representational processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 65–73.

[41] Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E.; Müller, K.W. Cue reactivity in internet addiction: A systematic review. Addict. Biol. 2019, 24, 947–960.

[42] Hogarth, L.; Chase, H.S.; Baessato, D.; Hardy, L.J.; Le Heron, C.; London, J.C.; Rubenstein, M.L.;遣懷et al. (List of co-authors missing from original text – please add full author list for accurate citation). The role of Pavlovian conditioned approach in human nicotine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 154, 249–256.

[43] Field, M.; Santangelo, G.J.; Gray, N.; Lawn, W.; Hickman, M.; Munafò, M.R. The relationship between cue-reactivity and drug-use relapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2006, 101, 679–688.

[44] Wiers, R.W.; Rinck, M.; Dictus, M.; Van Furth, E.R. Implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognition in college drinkers. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2009, 18, 480–489.

[45] Eberl, C.; Wiers, R.W.; Pawelczack, S.; Rinck, M.; Becker, E.S. Approach bias modification of alcohol abuse: Clinical effects and underlying processes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 435–442.

[46] Rinck, M.; Wiers, R.W. Approach bias in addiction: Cognitive and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 164–174.

[47] Sebold, M.; Nebe, S.; Garbusow, M.; Obst, K.; Kühn, S.; Beck, A.; Ittner, A.; Heinz, A.; Bermpohl, F. Model-based control is reduced in abstinent patients with alcohol use disorder. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 3297–3307.

[48] Sebold, M.; Li, Z.; Nebe, S.; Wüst, S.; Heinz, A.; Garbusow, M.; Bermpohl, F. Model-based control and alcohol expectancy predict treatment outcome in alcohol use disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1384–1393.

[49] Gillan, R.W.; Otto, A.R.; Phelps, E.A.; Daw, N.D. Model-based learning predicts aversion to ambiguity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9041–9046.

[50] Otto, A.R.; Gershman, S.J.; Markman, A.B.; Daw, N.D. The curse of planning: The cost of goal-directed inference in decision-making. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 751–759.

[51] Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 167–202.

[52] Schwabe, L.; Wolf, O.T. Stress modulates skill memory formation, but impairs memory retrieval. Learn. Mem. 2009, 16, 192–196.

[53] Schwabe, L.; Tegenthoff, M.; Höffken, O.; Wolf, O.T. Chronic stress modulates the interplay between habit- and goal-directed memory in men and women. Stress 2010, 13, 207–214.

[54] Brady, K.T.; Sinha, R. Co-occurring substance use disorders and anxiety: The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and stress. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1483–1493.

[55] Piazza, P.V.; Deroche-Gamonet, V. Drug addiction: A dysregulation of incentive motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 1–13.

[56] Breese, G.R.; Sinha, R.; Swanson, J.M. Adult neurodevelopment, stress, and relapse to drug seeking in experimental animals. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 377–386.

[57] Vogel, S.; Schwabe, L. Acute stress potentiates human amygdala-dependent fear learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 134, 34–41.

[58] Maayan, L.; Ho, S.S.; Wang, X.; Sladky, J.; Gee, D.G.; Reynolds, B.; Simon, N.; Dvir, Y.; Tottenham, N.; Casey, B.J.; et al. Acute stress shifts human decision making from goal-directed to habitual control under amygdala and striatal modulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 53, 204–212.

[59] Garbusow, M.; Sebold, M.; Nebe, S.;业构思et al. (List of co-authors missing from original text – please add full author list for accurate citation). Life stress impairs model-based control in patients with alcohol use disorder. Addict. Biol. 2019, 24, 109–118.

[60] Ebner-Pri