Non-invasive brain stimulation (NBS) techniques have become increasingly vital in understanding Learning And Memory processes in both healthy individuals and those with brain injuries. Methods like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) offer a unique way to modulate brain activity in specific cortical areas and across brain networks, with effects varying based on stimulation parameters. These techniques serve as powerful tools in neuropsychological research, allowing for the disruption of ongoing brain activity to study brain-behavior relationships, the timing of cognitive processes, and causal connections. When combined with real-time electroencephalography (EEG) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), TMS and tDCS provide interference capabilities alongside high temporal and spatial resolution recording of brain activity. This integration allows for: (1) deeper insights into physiological and behavioral interactions, (2) the testing and refinement of cognitive models, and (3) the potential development of improved neurorehabilitation strategies for learning and memory impairments.

The primary objectives of NBS research in the realm of learning and memory are threefold: (1) to pinpoint the underlying neuropsychological processes and neurobiological components; (2) to explore the diagnostic and restorative potential of NBS for learning and memory dysfunctions in diverse patient populations; and (3) to evaluate the effectiveness of NBS for cognitive enhancement in healthy individuals.

This article will first explore neuropsychological definitions of memory and learning. Following this, we will present a comprehensive review of existing research investigating the neurobiological mechanisms of memory and the application of NBS to enhance memory functions in both clinical and healthy contexts. Finally, we will address methodological considerations, limitations, and the future promise of NBS in advancing our understanding and treatment of learning and memory.

Neuropsychological Frameworks of Learning and Memory

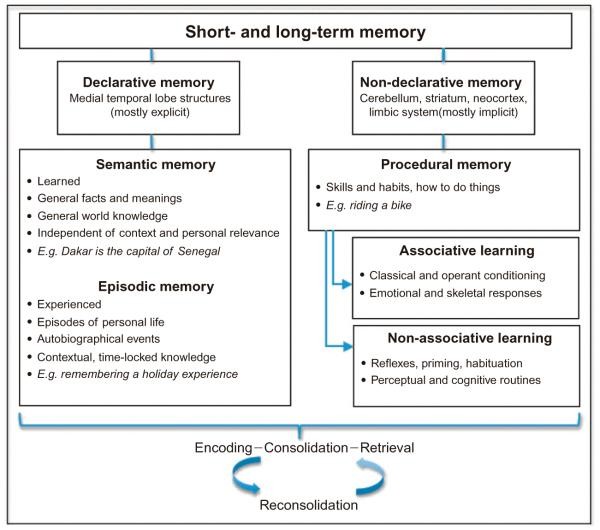

Learning and memory, fundamental cognitive functions, are composed of numerous interacting subcomponents. These components can be categorized based on various dimensions, such as time or the nature of the content and acquisition processes involved (Fig. 55.1). The cognitive architecture of learning and memory is intricate, characterized by significant interplay and overlap among its core elements. Consequently, developing a fully comprehensive taxonomy remains a challenge for both neuropsychological and neurobiological models.

Fig. 55.1.

A significant step in understanding the neurobiological basis of memory was Squire’s (1987, 2004) differentiation between declarative and nondeclarative memory systems, distinguished by their reliance on different brain structures (Cohen and Squire, 1980). Declarative memory, encompassing semantic and episodic memory, is crucial for everyday memory functions and is often impaired in amnesia. It is primarily associated with the medial temporal lobe, particularly the hippocampus. Nondeclarative memory, which includes procedural memory and motor skill learning, depends largely on the striatum, cerebellum, and cortical association areas (Cohen and Squire, 1980). Procedural memory also includes associative learning like classical and operant conditioning, and non-associative forms like priming, habituation, and the learning of perceptual and cognitive routines. Motor learning, often viewed as less cognitive, is generally distinguished from non-motor memory functions. However, declarative and nondeclarative memory are interactive and partially overlapping systems.

The distinction between explicit and implicit memory is historically linked to declarative and nondeclarative memory. Declarative memory (semantic and episodic) is often equated with explicit memories, which are conscious and verbally accessible. Nondeclarative memory is considered implicit, a subconscious and nonverbal form of memory. While declarative memory is generally acquired explicitly and nondeclarative memory implicitly, this is an oversimplification. Declarative memories can be formed subconsciously (e.g., emotional memories, subliminal priming), and nondeclarative memories can be acquired consciously (e.g., learning sports or musical instruments).

William James (1890) introduced another key dichotomy based on memory duration: short-term memory (STM) versus long-term memory (LTM). Initially, STM and LTM were thought to rely on separate neural systems. However, more recent theories suggest that the neural representations active during encoding are also engaged in STM and LTM retrieval. These models propose that medial temporal lobe structures are critical for establishing new memories, regardless of duration, with similar binding processes active in both STM and LTM (Wheeler et al., 2000; Jonides et al., 2008). A related temporal division separates retrograde and anterograde memory (Hartje and Poeck, 2002; Markowitsch and Staniloiu, 2013). Retrograde memory concerns access to past memories to inform current decisions, while anterograde memory and future thinking support long-term goal pursuit (Boyer, 2008).

These dichotomies highlight the complexity of memory processes and provide a framework for NBS research. NBS can help investigate whether disrupting specific brain regions selectively affects certain types of memory (e.g., Basso et al., 2010) or the timing at which disrupting a region interferes with memory stages (e.g., Oliveri et al., 2001). NBS can also explore relationships between different memory processes and compare NBS effects in healthy individuals versus those with memory deficits.

Memory is also intertwined with time perception, attention, and the emotional content of memories. Brain circuits for these functions overlap with memory-related areas. Increased memory load can lengthen perceived time intervals (Bailey and Areni, 2006), and subjective long time perception involves the medial temporal cortex (Noulhiane et al., 2007). State-dependent models propose that temporal information is encoded through time-dependent neural changes like short-term synaptic plasticity (Karmarkar and Buonomano, 2007). Short time intervals are encoded within the context of memory events in local neural networks. Short-term plasticity in state-dependent networks may provide memory traces of recent stimulus history (Buonomano, 2000), similar to how long-term plasticity supports learning experiences (Martin et al., 2000). NBS offers a way to investigate these complex questions with greater spatial and temporal precision than pharmacological interventions, which also impact working memory and temporal processing (Rammsayer et al., 2001).

Current research aims to integrate these findings into comprehensive models of memory networks. Debates continue regarding the role of attention in memory, particularly parietal regions in episodic memory retrieval. The Attention to Memory (AtoM) model suggests the dorsal parietal cortex manages top-down attention driven by retrieval goals, while the ventral parietal cortex handles automatic bottom-up attention to retrieved memory output (Ciaramelli et al., 2008; Cabeza et al., 2011). Cabeza and colleagues (2011) propose parietal regions control attention similarly in memory and perception. Orienting-related activity overlaps in the dorsoparietal cortex (DPC), and detection-related activity in the ventroparietal cortex (VPC). Both DPC and VPC show strong connectivity with the medial temporal lobe (MTL) during memory tasks, shifting to visual cortex connectivity during perception. The DPC collaborates with the prefrontal cortex (PFC) for top-down attention to retrieval paths, while the VPC, with the MTL, activates episodic features. Modern memory models emphasize dynamic network interactions and plasticity. While brain imaging provides valuable data, it lacks causal insights (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2012). NBS offers a transformative approach to address causality in memory research.

Procedural Memory

Procedural memory, particularly motor learning, involves improving motor skills through practice, leading to lasting neural changes. Key brain areas include the primary motor cortex, premotor and supplementary motor cortices, cerebellum, thalamus, and striatal areas (Karni et al., 1998; Muellbacher et al., 2002; Seidler et al., 2002; Ungerleider et al., 2002). The parietal cortex is also involved in accessing stored motor skills and visuospatial processing during motor learning, as seen in apraxia patients (Halsband and Lange, 2006). Frontoparietal networks become crucial for skill consolidation and storage after learning is established (Wheaton and Hallett, 2007).

Motor learning shares subprocesses with nonmotor memories: encoding, consolidation, long-term stability, and retrieval (Karni et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 2005). A short-term motor memory system may exist in the primary motor cortex (Classen et al., 1998). Robertson (2009) suggests that motor and nonmotor memory processes may share neuronal resources during wakefulness but diverge during sleep. The MTL, vital for declarative memory, also contributes to implicit procedural learning (Schendan et al., 2003; Robertson, 2007; Albouy et al., 2008). During sleep, motor and nonmotor memory systems may functionally separate, facilitating independent offline consolidation (Robertson, 2009). NBS studies have been instrumental in uncovering these insights.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory (STM) is essential for cognition, maintaining information for brief periods (seconds). Multistore models differentiate STM from LTM. Amnesic patients can have intact STM despite LTM impairments (Scoville and Milner, 1957; Cave and Squire, 1992), and conversely, STM can be impaired while LTM remains functional (Shallice and Warrington, 1970). William James (1890) described STM (primary memory) as conscious short-term sensory stimuli maintenance, and LTM (secondary memory) as reactivating past experiences not consciously available between encoding and retrieval. This led to the idea that STM and LTM are based on separate neural systems, with STM involving repeated cellular excitation and LTM involving synaptic structural changes after hippocampal-dependent consolidation (Hebb, 1940s). NBS, especially TMS combined with EEG or MRI, has provided valuable insights into these neurobiological questions.

Baddeley’s multistore model (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974; Baddeley, 1986) describes STM with a “verbal buffer” (phonological loop) and a “visuospatial sketchpad,” later adding an “episodic buffer” drawing on these and LTM (Baddeley, 2000). A “central executive” orchestrates these components. These cognitive models are well-suited for hypothesis testing with NBS.

Unitary store models propose the MTL is involved in both STM and LTM, establishing new representations regardless of duration. Amnesic patients can retain information not needing binding processes, explaining preserved retrieval of consolidated pre-injury memories. Jonides and colleagues (2008) concluded STM and LTM are not separable, with STM being temporarily activated LTM representations. Studies support this (Ranganath and D’Esposito, 2001; Hannula et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2006a, b), suggesting initial neural representations are also long-term repositories, active during encoding, STM, and LTM retrieval (Wheeler et al., 2000). Chronometric brain stimulation experiments can further explore these questions (e.g., Mottaghy et al., 2003a).

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM) involves mechanisms that stabilize or strengthen acquired memories over time, making them resistant to interference (Brashers-Krug et al., 1996; McGaugh, 2000; Dudai, 2004). Consolidation, measured by performance changes between testing and retesting (Robertson et al., 2004; Walker, 2005), directly reflects “offline” changes.

LTM, often under “declarative memory,” includes episodic and semantic memory, primarily relying on MTL structures. Episodic memory is context-specific, like holiday memories, while semantic memory is context-independent, general knowledge. Nondeclarative memory, like procedural memory, also involves LTM consolidation.

Long-term storage involves encoding, short-term storage, STM to LTM consolidation, and reconsolidation. Consolidation is structured for efficient retrieval. Muellbacher and colleagues (2002) pioneered NBS to study these processes in humans. During consolidation, memories can change quantitatively (enhancement) and qualitatively (e.g., sequence awareness) (Wagner et al., 2004; Walker, 2005; Robertson and Cohen, 2006). Chronometric brain stimulation helps clarify these issues. Consolidation may involve neuronal reactivation (signal increase), noise reduction, or both, all examinable with NBS. Offline performance changes are linked to neuronal reactivation (Rasch et al., 2007), and TMS could test if disrupting reactivation impairs consolidation.

Sleep plays a key role in memory consolidation (Walker et al., 2002; Korman et al., 2007). The synaptic homeostasis hypothesis suggests wakefulness increases synapse efficacy and number, adding network noise. Noise reduction improves signal-to-noise ratio. Slow-wave sleep reduces synaptic strength and noise (Tononi and Cirelli, 2003, 2006), and is associated with learning and plasticity (Huber et al., 2004, 2006; De Gennaro et al., 2008). tDCS is used to test these ideas, and TMS-EEG studies support underlying hypotheses (e.g., Marshall et al., 2004, 2011).

Encoding and Retrieval

Encoding involves PFC-guided processes that actively maintain event features across neocortical areas (Miller and Cohen, 2001; D’Esposito, 2007). TMS and tDCS are useful for testing these ideas and assessing spatial and temporal aspects of neural substrates.

The MTL binds these representations for optimal later retrieval (Cohen and Eichenbaum, 1991; Squire and Zola, 1998). PFC and MTL activity during encoding correlates with retrieval success (Paller and Wagner, 2002). Intermediate processes like consolidation further stabilize memories (Squire, 1984; Nadel et al., 2000; Paller, 2002). Encoding includes bottom-up sensory and top-down selection/engagement processes (Shimamura, 2011). NBS is valuable for interfering with neural activity in a controlled manner during these stages.

Retrieval of episodic memories depends on recalling encoded contextual features like time, place, and emotions (Mitchell and Johnson, 2009). Source memory is crucial for episodic memory (Tulving, 2002; Shimamura and Wickens, 2009). MTL reinstates these features during retrieval (Eldridge et al., 2005; Moscovitch et al., 2006). The PFC, involved in top-down executive control, is also associated with successful retrieval (Buckner et al., 1998; Dobbins et al., 2002; Simons and Spiers, 2003). The HERA (Hemispheric Encoding/Retrieval Asymmetry) model (Tulving et al., 1994) suggests left PFC is for encoding and semantic retrieval, while right PFC is for episodic retrieval. Early imaging studies showed encoding/retrieval asymmetry in PFC (Cabeza and Nyberg, 2000; Haxby et al., 2000; Fletcher and Henson, 2001). The HAROLD (Hemispheric Asymmetry Reduction in Older Adults) model (Cabeza, 2002) suggests prefrontal activity becomes less lateralized with age. PFC’s role can be studied with TMS or tDCS, as it is easily accessible to NBS (e.g., Gagnon et al., 2010, 2011).

Besides MTL, PFC, and feature-storing cortical sites, parietal areas are important for episodic memory retrieval (Wagner et al., 2005; Cabeza et al., 2008). The COrtical Binding of Relational Activity (CoBRA) theory proposes the VPC binds episodic features and links them to LTM networks (Shimamura, 2011). CoBRA and AtoM models both link MTL and VPC, though AtoM emphasizes bottom-up processes and CoBRA emphasizes event-related activity integration. Paired-pulse TMS and TMS with imaging can examine corticocortical interactions in these models.

Prospective Memory

Prospective memory is the intention to perform future actions, crucial for future-oriented behavior. It requires retaining intentions and activating them at the right time or context (Ellis et al., 1999). Depending on the delay and trigger (external or internal), prospective memory involves working and long-term memory, and attentional processes (Wittmann, 2009). Intentions gain special status during encoding, tagged as uncompleted. Temporal areas are active during cue presentation, possibly for stimulus-driven attention (Reynolds et al., 2009). The delay period involves cognitive activity that prevents active rehearsal, differentiating prospective memory from WM or vigilance (Reynolds et al., 2009; Burgess et al., 2011). Prospective memory and WM rely on executive processes but engage different brain areas. WM involves dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), while prospective memory is mainly associated with the rostral PFC (Okuda et al., 1998, 2007; Reynolds et al., 2009), linked to “future thinking” (Atance and O’Neill, 2001). NBS can experimentally test these theoretical considerations.

Working Memory

Working memory (WM) involves temporary, active maintenance and manipulation of information for complex tasks, while filtering irrelevant information. It manipulates external (experienced) or internal (retrieved) stimuli, including encoding and retrieval stages. The PFC is integral for WM (Missonnier et al., 2003, 2004; Jaeggi et al., 2007), and NBS offers approaches previously limited to animal models.

WM is highly dependent on top-down processing and selective attention. Top-down modulation improves signal-to-noise ratio by enhancing relevant stimuli and reducing irrelevant ones (Gazzaley and Nobre, 2012). Successful information manipulation is needed for encoding and integrating memory with higher cognitive functions like decision-making, imagery, and language. State-dependency NBS designs (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2008) can selectively modulate information items and shift signal-to-noise ratio, promising translational applications for WM deficits in the elderly or patients with ADHD, Parkinson’s, or schizophrenia.

Neural Mechanisms of Learning and Memory: Insights from NBS

Learning and memory research employs diverse methods, including brain imaging during memory tasks, EEG correlations with memory recall, state change analyses, and lesion studies. These have provided valuable insights, but establishing cause-effect relationships is challenging. NBS uniquely addresses this (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2012).

While TMS and tDCS both alter excitability, their mechanisms differ (Wagner et al., 2007; Nitsche et al., 2008), leading to varied behavioral effects. Neuronavigated TMS probes the spatiotemporal roles of brain structures in learning and memory, revealing where and when processes occur and their interplay. tDCS has lower spatial and temporal resolution, limiting its use for spatiotemporal properties. The following section focuses on TMS as a “virtual lesion” inducer in healthy brains (Pascual-Leone et al., 2000). Research in this area has expanded rapidly.

Virtual Lesions in Healthy Subjects to Assess Memory Functions

Early studies of brain-cognition links came from WWI soldiers with brain lesions (Lepore, 1994). Luria’s work with WWII veterans furthered neuropsychology (Luria, 1972).

Patient lesion studies have disadvantages: uncontrolled lesion size, comorbidities, and age. Modern imaging like PET and fMRI offer excellent spatial resolution and controlled designs, but limited temporal resolution and lack of causality insights. EEG offers high temporal resolution but limited spatial resolution.

TMS-induced “virtual lesions” in healthy brains overcome many of these issues (Pascual-Leone et al., 1999; Walsh and Pascual-Leone, 2003). TMS interferes with brain activity, probing cortical area contributions. However, “virtual lesion” mechanisms are complex, involving inhibitory and excitatory interplay, oscillator disruption, and functional connectivity changes across networks, not just simple excitability changes.

TMS is widely used in motor learning and memory research (Bütefisch et al., 2004; Censor and Cohen, 2011), but less for nonmotor memory. Recent TMS-EEG and TMS-fMRI combinations are promising for nonmotor memory exploration (Miniussi and Thut, 2010; Thut and Pascual-Leone, 2010), unraveling local and distant stimulation effects and functional connectivity.

WM and STM NBS studies often target the DLPFC or parietal cortex, considered core memory structures. They typically use delayed response or n-back tasks. The Sternberg task (Sternberg, 1966) is a classic delayed match-to-sample task. N-back tasks require comparing stimuli to those n trials back. n=1 tasks involve continuous maintenance and matching, while n>1 tasks also require manipulation. Increased n reflects attention reallocation from matching to WM, shown by decreased P300 amplitudes (Watter et al., 2001). These tasks tap different processes and are discussed separately. Delayed match-to-sample tasks are under STM, and n-back tasks under WM. Another section covers encoding, consolidation, and retrieval.

NBS studies on memory have grown rapidly, using single-pulse TMS, paired-pulse TMS, repetitive TMS (rTMS), and theta-burst stimulation (TBS). Tasks vary in cognitive demands (attentional, sensory, motor, verbal/nonverbal, spatial/nonspatial, maintenance/manipulation), and stimulation parameters (pattern, timing, duration, intensity, location) vary across studies. Memory tasks and TMS methodology vary greatly. Online stimulation differs from offline, as brain areas are activated by both TMS and task performance, affecting outcomes. Some studies focus on accuracy, others on reaction times (Table 55.1). Accuracy is generally more critical than reaction time in memory tasks. The act of receiving TMS can influence attention, requiring careful control.

Table 55.1.

Synopsis of peer-reviewed, published studies applying noninvasive brain stimulation in the memory domain.

| Reference | n | Regions stimulated | Stimulation protocol | Task | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMS in short-term memory | |||||

| Beckers and Hömberg (1991) | 24 | OC | Various intensities at 40–120 ms, during delay, active/sham | Trigram identification task and visual DMS | Stim during delay impaired identification of trigrams as compared to sham. Stim during delay of DMS decreased memory scanning rates. No impact on accuracy. |

| Kessels et al. (2000) | 8 | R/L PPC (P3/P4) | 200 ms of 25 Hz rTMS at 115% rMT, during delay, active/sham | Spatial DMS | Stim to right PC during delay increased RT compared to left stim, but not sham (~561 ms vs. ~522 and ~540 ms). |

| Mottaghy et al. (2002b) | 8 | L DMPFC, DLPFC, VPFC | 10 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, comparison with baseline | Spatial or face DMS (objects and faces) | Stim to DMPFC increased error rate for spatial task compared to baseline (2.88 vs. 1.58). Stim to DLPFC increased error rates for spatial (4.25 vs. 2.21) and face task (3.38 vs. 2.17). Stim to VPFC increased error rates for face task (3.63 vs. 1.96). No impact on RT. |

| Herwig et al. (2003) | 9 | L PFC, PMC, PC (fMRI-guided), homolog regions (control) | 3 s of 15 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during delay (second half) | Verbal DMS (1 or 6 letters) | Stim over left PMC (~14.3 vs. 9.5%) but not PC or PFC increased error rate. No impact on RT. |

| Koch et al. (2005) | 9 | R PPC (P6), premotor cortex (SFG), and DLPFC (F4) | 300 ms of 25 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during delay or decision, active/sham | Matching of spatial sequences | Stim over PPC (~29%) and DLPFC (~22%) but not SFG during the delay phase impaired RT. Stim over DLPFC during the decision phase selectively impaired RT (~38%). No impact on accuracy. |

| Desmond et al. (2005) | 17 | R superior Cb | sp TMS at 120% rMT, during delay, active/ non-active trials/ sham | Verbal DMS and motor control task | Stim at the beginning of the delay phase increased RT on correct trials compared to non-active trials, sham, and motor control task. No effect on accuracy. |

| Kirschen et al. (2006) | 30 | Left IPL | 3 sp at 120% rMT, during delay (at 1,3,5 s), active/sham control region | Verbal DMS (phonologically similar/ dissimilar pseudo-words and distractors) | Stim during delay improved RT for similar pseudo-words as compared to sham. Accuracy improved marginally. No difference observed between TMS and placebo scores for dissimilar pairs. |

| Luber et al. (2007) | 44 | Exp. 1: Midline PC (precuneus) or left DLPFC Exp. 2: Midline PC (precuneus) | 100% rMT, active/sham rTMS Exp. 1: 1 or 5 Hz (7 s) or 20 Hz (2 s), during delay Exp. 2: 5 Hz (7 s), during delay or decision | Verbal DMS (1 or 6 letters) | Exp. 1: Only 5 Hz rTMS over PC but not DLPFC during delay phase improved 6-letter RT compared to sham (626 vs. 702 ms, ~11%) and 1-letter RT (491 vs. 542 ms, ~ 9%). Exp. 2: 5 Hz rTMS over PC during delay but not decision phase improved RT by 88 ms. 1-letter accuracy improved during decision phase compared to sham (~97 vs. ~90, ~7%). |

| Hamidi et al. (2008) | Exp. 1: 30 Exp. 2: 24 | Exp. 1: R/L DLPFC, SPL, PCG (control) Exp. 2: R/L FEF, IPS, PCG (control) | 3 s of 10 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during delay, active/control | Spatial DMS | Exp. 1: Stim over SPL improved RT ~2% as compared to PCG-control (~950 ms vs. ~970 ms). Stim over LH impaired accuracy more as stim over RH (largest effect over DLPFC). Stim was more disruptive if applied contralaterally to the visual field (faster/slower RT for LH/RH stim). Exp. 2: Stim decreased accuracy overall and specifically for contralaterally presented stimuli. |

| Luber et al. (2008) | 15 (sleep deprived for 48 h s) | BA 19 and midline PC, BA 18 (control), (as localized in fMRI) | 7 s of 5 Hz rTMS at 100%rMT, during delay, active/sham | Visual DMS | Stim to the upper middle occipital region only reduced sleep-deprivation induced RT deficit compared to sham (1026 ms vs. 1169 ms). No impact on accuracy or non-sleep deprived subjects (state-dependency). |

| Hamidi et al. (2009) | 24 | R/L DLPFC, SPL, and PCG (control) | 3 s of 10 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during decision, active/ control | Spatial DMS (recognition) and recall | Recognition: Stim to right DLPFC resulted in accuracy improvement, stim to left DLPFC led to reduced accuracy. Recall: Stim to right DLPFC resulted in reduced accuracy. No impact of stim over SPL. |

| Cattaneo (2009) | Exp. 1: 14 Exp. 2: 11 | OC (V1, V2) and vertex | sp TMS at 65% MSO, at beginning or end of delay, compared to baseline | Visual Imagery and visuospatial STM Exp. 1: at end of delay Exp. 2: at beginning of delay | Exp. 1: Stim facilitated both tasks compared to vertex stim and baseline. Exp. 2: Stim impaired STM compared to vertex and baseline but not visual imagery. No impact on accuracy. |

| Preston et al. (2009) | 32 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 5 5-s trains of 10 Hz rTMS, ITI 10 s, at 100% rMT, offline, active/sham | Verbal DMS | Stim decreased correct response RT in active (−21%) compared to sham (+0.3%). No impact on accuracy. |

| Yamanaka et al. (2010) | 52 | R/L PC | 5 Hz rTMS at 100% rMT, during delay (6 s), active/sham | Spatial DMS and attentional control task | Stim over right PC during delay improved RT ~7% compared to sham (~800 ms vs. ~865 ms). Increase of frontal oxygenated hemoglobin during DMS and decrease during control task. |

| Silvanto and Cattaneo (2010) | 12 | Exp. 1: R/LV5/MT (2 coils) Exp. 2: R/L lateral OC (2 coils) | sp TMS at 120% PT, at 3 s into delay, baseline phosphene | Delayed visual motion discrimination | Exp. 1: Reported phosphene motion was influenced by the motion component of the memory item: enhanced when direction was the same as in baseline phosphene, weakened if opposite direction. Exp. 2: No relation between task and phosphenes after stim of lateral occipital region. |

| Hannula et al. (2010) | Exp. 1: 6 Exp. 3: 6 | MFG area with/without S1 connection | sp TMS at 120% rMT, at 300 or 1200 ms into delay, baseline control | Tactile STM (discrimination) without (Exp. 1) or with (Exp. 3) distraction | Exp. 1: Stim delivered during early but not late delay over MFG regions with connection to S1 decreased RT ~15% compared to baseline (~730 ms vs. ~860 ms). Exp. 3: Distraction prolonged mean RT by 5%. |

| Feredoes et al. (2011) | 16 | R DLPFC, combined with fMRI | 3 sp TMS at 110% rMT or 40% rMT (control), during delay | Visual DMS (face or house) with/without distractor interference | Stim (time-locked to distractors) over DLPFC increased activation in posterior areas (that represented stimuli but not distractors) only when distractors were present. |

| Zanto et al. (2011) | 20 | R IFJ (as localized in fMRI), combined with EEG | 10 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 120% rMT offline, active/sham | Visual DMS (motion direction or color of dots) | Stim led to a decline of P1 and accuracy during the first half but not second half of the color condition, no effects during motion condition (P1 modulation predicted accuracy changes). The magnitude of phase locking value in the alpha band (but not beta or gamma) decreased after rTMS. |

| Higo et al. (2011) Exp. 2 | 9 | L fO (as localized in fMRI in Exp. 1) | 15 min 1 Hz rTMS, offline, adjusted to RMT, active | Visual delayed matching to stimulus class (houses, body parts, faces) | TMS over fO disrupted top-down selective attentional modulation in the occipitotemporal cortex but did not alter bottom-up activation. The fO may play a role in regulating activity levels of representations in posterior brain areas. |

| Savolainen et al. (2011) | 12 | MFG area with/without S1 connection | sp TMS at 120% rMT, at 300 ms into delay, baseline control | Tactile STM (discrimination) with tactile or visual distractor | Stim over MFG region with S1 connection followed by tactile (but not visual) distractor decreased RT~4% compared to baseline (~770 ms vs. ~800 ms). |

| Soto et al. (2012) Exp. 2 | 8 | L SFG and LOC (as localized in fMRI Exp. 1) | 15 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 55% MSO, offline, active/sham | Visual and verbal DMS | Stim to left SFG increased RT for recognition of colored shapes compared to sham. Stim to the LOC increased RT for recognition of written words compared to sham. No impact on accuracy. |

| Morgan et al. (2013) | 20 | R PC, L IFG | 40 s train of cTBS at 80% aMT, offline, active/sham | Object color, angle averaging, and combined task | Stim to right PC or left IFG selectively impaired WM for the combined task, but not single feature tasks as compared to sham. |

| van de Ven et al. (2012) | 12 | Lateral OC | sp TMS at 110% PT at 100, 200, or 400 ms into delay, active/ sham | Modified change detection task with low or high memory loads | Stim delivered at 200 ms into the delay phase decreased accuracy for high but not low memory loads in the contralateral visual field compared to sham. |

| TMS in working memory and prospective memory | |||||

| Mottaghy et al. (2000) | 14 | R/L DLPFC, Fz (control), combined with PET | 30 s of 4 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during task, active/control | Verbal 2-back, 0-back (control) | Stim over either R/L DLPFC reduced accuracy and rCBF in the targeted area as well as afferent networks specific to each hemisphere. Stim to Fz had no effect on WM task. Performance on the control task was not affected by stim. |

| Mull and Seyal et al. (2001) | 7 | R/L DLPFC | spTMS at 115% rMT, at 400 ms into delay, active/no TMS | Verbal 3-back | Stim over L DLPFC increased error rate compared to no TMS control (5.4%). No impact of stim over R DLPFC. |

| Oliveri et al. (2001) | 35 (5 Exp.: 8, 6, 6, 25, 6) | Exp. series 1: R/L or bilateral temporal (T5/T6) and parietal (P4/P5) Exp. series 2: Bilateral SFG and DLPFC | Uni- or bilateral spTMS at 130% rMT, at 300 or 600 ms, active/ baseline | Spatial 2-back Visual-object 2-back (abstract patterns) | Exp. series 1: Bilateral parietal stim at 300 ms increased RT in visuospatial task compared to temporal (11%) and baseline (20%). Bilateral temporal stim at 300 ms impaired RT in visual-object task. No impact on accuracy. Exp. series 2: Bilateral stim over SFG at 600 ms increased RTs in visuospatial task compared to baseline (11%), whereas bilateral stim over DLPFC at 600 ms interfered in both tasks with accuracy (visuospatial: 10%, visual- object: 13%) and RT (visuospatial: 6%, visual-object: 6%). |

| Sandrini et al. (2003) | 12 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 0.5 s of 20 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham/baseline | Verbal LTM: Recognition of unrelated/related word pairs after 1 h | Impaired recognition accuracy of unrelated word pairs after stim over R and L DLPFC during encoding and right PFC in retrieval. No impact on RT besides faster RT for related as compared to unrelated words. |

| Mottaghy et al. (2003a) | 6 | R/L MFG, inferior PC | sp TMS at 120% rMT, at 140-500 (at 10 time points, ISI 40 ms) into delay, after every 4th letter, active/control | Exp. 1: Verbal 2-back Exp. 2: Choice reaction (control task) | Impaired accuracy occurred after stim of R PC (180 ms) of L PC (220 ms) and R MFG (220 ms), and L MFG (260 ms). RT was impaired only after L MFG stim (180 ms). No impact on control task. |

| Mottaghy et al. (2003b) | 14 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 30 s of 4 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during task, active/control/ baseline | Verbal 2-back, 0-back (control task) | Stim over L DLPFC led to a shift of BBR towards the SFG and to a positive BBR in anterior parts of the SFG. Stim over R DLPFC led to a shift of the BBR to left posterior and inferior IFG. Baseline measurements indicated a negative BBR in the left MFG and no significant BBR in the right MFG. |

| Rami et al. (2003) | 16 | HF stim to R/L DLFPC and right Cb, LF stim to L DLPFC | 10-s trains of 1 or 5 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, 30 s intervals, during encoding and retrieval, active/ baseline | STM (digits forward), WM (digits backward, letter- number sequencing WAIS III), episodic memory (RBMT), verbal fluency | HF stim over L DLFPC impaired verbal episodic memory as compared to HF stim over R DLPFC, LF stim over L DLPFC, and baseline. |

| Postle et al. (2006) | R: 5 L: 7 | R/L DLPFC, SPL, PCG (control) (as localized with fMRI) | 6 s of 5 Hz rTMS at 100% rMT, during delay, active/control | Verbal STM or WM | Stim over DLPFC impaired accuracy of WM but not STM compared to control. Stim over SPL impaired accuracy of WM and STM. No impact on RT. |

| Osaka et al. (2007) | 8 | L DLPFC, Cz (control) | pp TMS (ISI 100 ms) at .47 T, during delay, active/sham/control | Reading span task (maintain target words) | Stim decreased mean accuracy compared to sham or stim over Cz (10.9% and 7.5%). |

| Sandrini et al. (2008) | Exp. 1: 9 Exp. 2: 14 Exp. 3: 9 | R/L DLPFC | 0.5 s of 10 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, at end of delay, active/sham | Exp. 1: combined verbal/spatial 1-back Exp. 2: combined verbal/spatial 2-back Exp. 3: 2-back with one domain only | R DLPFC stim impaired RT in the verbal condition (~834 ms vs. ~790 and ~803 ms), whereas L DLPFC stim impaired RT in the spatial condition compared to opposite side and sham (792 ms vs. 728 and 737 ms). No impact on accuracy, variation of only one domain, or 1-back task. |

| Imm et al. (2008) | 12 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4), inferior PC (P3/P4) | sp TMS at 100% rMT, at 250, 450, 650, or 850 ms into delay, active | Audioverbal 2-back Pitch 2-back | Stim over RH increased RT in the pitch 2-back at 650 and 850 ms (724 and 850 ms vs. 656 ms). Stim over P3 increased RT in the audioverbal 2- back at 450 ms. |

| Basso et al. (2010) | Exp. 1: 27 Exp. 2: 24 Exp. 3: 18 | R/L DLPFC, interhemispheric sulcus (control) | spTMS at 100% rMT, delivered 300 ms into delay, active/ control | Exp. 1: WM (medium = 3, high = 5) and lexical decision (word/ pseudoword), prospective condition (react to specific words); Exp. 2: prospective condition 1 or 3 words; Exp. 3: with TMS | Stim increased error rates of the PM task more than the WM task and compared to sham. Exp. 1 and 2: Higher PM demand affected WM only at higher loads. Exp. 3: Stim over R/L DLPFC impaired accuracy of PM task regardless of WM load, while effect on WM was marginal. |

| Costa et al. (2011) | Exp. 1: 8 Exp. 2: 8 | Exp. 1: R/L BA 10 (frontal pole), Cz (control) Exp. 2: L BA 46 (DLPFC), Cz (control) | 20 s of cTBS (3-pulse bursts at 50 Hz every 200 ms) at 80% aMT | Verbal forward/ backward memorization task with simultaneous response to target word (PM task) | Exp. 1: Stim over left BA 10 decreased accuracy in PM compared to Cz stim (58.6% vs. 73.4%). Exp. 2: Stim over left DLPFC had no significant effect on accuracy or RT. |

| TMS in general learning and memory | |||||

| Grafman et al. (1994) | 5 | R/L hemisphere (F7/F8, T5/T6, P3/P4, O1/O2) | 5 p of 20 Hz rTMS at 120% rMT, during encoding (at 0, 250, 500, 1000 ms), active/sham | Verbal memory (word recall) | Stim over T5, F7, and F8 at 0 and 250 ms showed highest impairment of recall as compared to sham. Furthermore stim over T5 and F7 at 500 ms impaired recall. Stim over T5 and F7 also impaired the primacy effect. |

| Rossi et al. (2001) | 13 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 500 ms of 20 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham/baseline | Visual memory (indoor/outdoor images) | Stim over R DLPFC during retrieval impaired accuracy, while stim over L DLPFC during encoding and over R DLPFC during retrieval impaired discrimination. No impact of R DLPFC stim during encoding and L DLPFC stim during retrieval. |

| Epstein et al. (2002) | 10 | R/L DLPFC, Cz (control) | pp TMS (ISI 60 ms), 120% rMT, during encoding at 180 ms, active/controls/no stim | Visual memory (associate Kanji words and abstract patterns) | Stim during encoding over R DLPFC decreased accuracy compared to stim over L DLPFC. RT was not measured. |

| Floel et al. (2004) | 15 | R/L IFG | 0.5 s of 20 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, during encoding, active/ sham/no stim | Verbal (letters) and nonverbal (abstract shapes) memory | Stim over L IFG impaired word recognition, while stim over R IFG impaired image recognition, each as compared to opposite stim (words 20% and images 14%) or sham (words 24% and images 14%). No impact on RT. |

| Köhler et al. (2004) | 12 | L Inferior PFC (guided by fMRI) R inferior PFC and L PC (controls) | 5 p of 7 Hz rTMS at 100% rMT, during encoding, active/ control/no stim | During fMRI: semantic/non- semantic decisions, crosshair fixation During stim: semantic decisions After stim: verbal memory (recognition) | Stim over L PFC increased recognition accuracy compared to non-stim and control (R PFC, L PC). No impact on RT. But, RT for semantic decisions made under L PFC stim was impaired. |

| Skrdlantov et al. (2005) | 10 | L DLPFC | 0.9 Hz rTMS at 110% rMT, during task (192 p per subtest), active/sham | Verbal memory (word recall) Visual memory (facial recognition) | Stim over L DLPFC during task impaired free recall of words but not recognition of faces as compared to sham. |

| Kahn et al. (2005) | 14 | R/L posterior VLPFC, (guided by fMRI) | spTMS at mean 66% MSO, during encoding (btw 250- 600 ms), active/ baseline | Verbal memory (decision if 2/3- syllable word or peusdo-word, then surpise recognition task with confidence judgments) | Stim over L VLPFC impaired word memory (confidence), while stim over R VLPFC facilitated word and pseudo- word memory (confidence, difference strongest at 380 ms). Phonological decision accuracy was facilitated for words and pseudo- words after stim over R VLPFC (strongest at 340 ms). |

| Rossi et al. (2006) | 42 | R/L DLPFC or IPS (P3/P4) | 500 ms rTMS at 20 Hz at 90 or 120% rMT, during encoding, active/sham | Visual memory (indoor/outdoor images), visuospatial attention (Posner, control task) | L DLPFC stim interfered with encoding while R DLPFC stim interfered with retrieval. No impact of stim over IPS on encoding or retrieval even at higher intensity. However, stim over R IPS impaired RT in the attention task. |

| Schutter and van Honk (2006) | 11 | L OFC (Fp1), L DLPFC (F3) | 20 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 80% rMT, offline, active/sham | Visual memory (neutral, fearful, and happy faces) | Stim over L OFC improved memory for happy faces compared to sham. Stim over L DLPFC improved memory marginally for happy faces compared to sham. |

| Gallate et al. (2009) | 20 | L ATL (between T7/FT7) | 10 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 90% rMT, offline, active/sham | Verbal memory (false memories) | Stim decreased the number of false memories by 36% compared to sham (~3 vs. ~2 errors). |

| Sauseng et al. (2009) | Exp. 3: 7 Exp. 4: 13 | Exp. 3: R/L PC (P3/P4), Cz (control) Exp. 4: R/L PC (P3/P4), centroparietal control | 9 pulses of 10 Hz or 14 pulses of 15 Hz rTMS, at 110% rMT, during delay, active/ sham | Visual STM (memorize color of a square presented in one but not other visual hemifield) | 10 Hz rTMS to PC ipsilateral to the stimulus improved visual STM (Exp. 3/4: 40% less false alarms, 37% fewer missed trials), while contralateral stim over PC led to a decrease. No effect of 15 Hz rTMS over PC or 10 Hz rTMS over centroparietal sites. |

| Blanchet et al. (2010) | 16 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | ppTMS, ISI 3 ms, 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham | Verbal (letters) and nonverbal (shapes) memory, under full or divided attention | Stim over L DLPFC impaired recall as compared to stim over R DLPFC under full attention encoding (but not as compared to sham). Stim over R DLPFC impaired recall as compared to sham under divided attention encoding (but not as compared to stim over L DLPFC). |

| Gagnon et al. (2010) | 18 | R/L DLPFC | ppTMS, ISI 3 ms, at 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham | Verbal (letters) and nonverbal (abstract shapes) memory | Stim over L DLPFC during encoding decreased DR as compared to sham and stim over R DLPFC. Stim over the R DLPFC during retrieval decreased DR and hit rate compared to stim over L DLPFC. No significant differences between verbal/nonverbal material. |

| Gagnon et al. (2011) | 11 | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | ppTMS, ISI 15 ms, at 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham | Verbal (letters) and nonverbal (abstract shapes) memory | Stim over L DLPFC during encoding improved RT as compared to stim over R DLPFC or sham. Stim over R DLPFC during retrieval improved RT as compared to stim over L DLPFC. More false alarms for shapes than for words occurred after stim over R DLPFC or sham. |

| De Weerd et al. (2012) | 13 | R OC (V1) to interfere with lower-L (but not upper-R) quadrant | Priming with 20 trains of 30 pulses at 6 Hz (ITI 25 s) at 45% MSO, 6.7 min of 1 Hz rTMS at 50 MSO, 45 min after session 1 and 2, active/no stim | Visual orientation discrimination (day 1: lower L quadrant, upper R quadrant, day 2: opposite or vice versa) | Stim delivered 45 min after the first and second training session to interfere with lower-L quadrant strongly impaired learning as measured on the next day. This interference occurred only when training of the L visual field was followed by training of the R visual field before TMS and not vice versa. No differences between quadrants at baseline. |

| tDCS in short-term memory | |||||

| Marshall et al. (2005) | 12 | Bilateral RA/LA or RC/ LC DLPFC (F3/F4), S | 0.26 mA, intermittent on/off 15 s over 15 min, during task, ref mastoids, active/ sham | Visual STM (modified Sternberg) | Bilateral A and C stim both impaired RT as compared to placebo. No impact on accuracy. |

| Ferrucci et al. (2008) | 17 | A/C/S, R/L Cb and PFC (btw Fp1/F3 and Fp2/F4) | 2 mA, 15 min, offline, ref deltoid, active/ sham | Numerical STM (modified Sternberg) | C-tDCS over PFC improved RT ~6% compared to sham (~625 ms vs. ~665 ms). No effect after A-tDCS. A-tDCS and C-tDCS blocked RT decrease induced by task repetition. |

| Berryhill et al. (2010) | 11 | A./C/S, R inferior PC (P4) | 1.5 mA, 10 min, during learning, ref left cheek, active/sham | Visual STM (recognition and free recall of objects) | C-tDCS selectively impaired WM on recognition tasks versus anodal and sham. No impact on free recall. |

| Gladwin et al. (2012) | 14 | A/S, L DLPFC | 1 mA, 10 min, during task, ref SOA, active/sham | Verbal STM (modified Sternberg) | A-tDCS improved RT when distractor was present compared to non- distractor and sham conditions. No impact on accuracy. |

| Heimrath et al. (2012) | 12 | A/C/S, R PC (btw P8/ P10), combined with EEG | 1 mA, 30 min, offline, ref btw P7/P9, active/ sham | Spatial DMS | While A-tDCS over RH impaired capacity for contralateral stimuli, C -tDCS improved it. Both A-tDCS and C-tDCS affected capacity for ipsilateral stimuli compared to sham. tDCS altered ERPs (N2, P2, N3) and oscillatory power in the alpha band at posterior electrodes. |

| tDCS in working memory | |||||

| Fregni et al. (2005) | 15 | A/C/S, L DLPFC (F3),A M1 (control) | 1 mA, 10 min, during task, ref SOA, active/sham/M1 | Verbal 3-back (sequential-letter task) | A-tDCS over L DLPFC improved accuracy by ~10% (21.7 vs. 19.8) and decreased number of errors by ~28% as compared to sham (4.7 vs. 6.9). No impact after C-tDCS over LDLPFC or A-tDCS over M1. No impact on RT. |

| Ohn et al. (2008) | 15 | A/S, L DLPFC (F3) | 1 mA, 30 min, during, ref SOA, active/ sham | Verbal 3-back (assessed 10, 20, and 30 min into stim, and 30 min after) | A-tDCS improved accuracy by 10% (at 20 min), 16% (at 30 min), 14% (at 30 min after) as compared to sham. No impact on error rates or RT. |

| Mulquiney et al. (2011) | 10 | A, L DLPFC (F3) | 1 mA, 10 min, during task, ref SOA active/ sham/tRNS | Pre and post stimulation: visual STM (one card task, 1-back), WM (2- back) During stimulation: STM (Sternberg) | A-tDCS decreased RT in WM (2-back) for correct responses by ~2% compared to sham. No impact on accuracy. No impact on STM tasks. |

| Teo et al. (2011) | 12 | A/S, L DLPFC (F3) | 1 or 2 mA, 20 min, during task, ref SOA, active/sham | Verbal 3-back during stim, STM (Sternberg) after stim | During the final 5 min of A-tDCS (2 mA) over L DLPFC RT improved significantly as compared to sham (~581ms vs. ~605.25 and ~629.49 ms). No impact on accuracy. No impact on STM after stim. |

| Zaehle et al. (2011) | 16 | A/C/S, L DLPFC (F3), combined with EEG | 1 mA, 15 min, offline, ref mastoid, active/ sham/control | Verbal 2-back (letters) | A-tDCS improved RT as compared to C-tDCS and resulted in amplified oscillatory power in the theta and alpha bands under posterior electrode sites. C-tDCS had opposite effects on EEG measures. No impact on accuracy. |

| Andrews et al. (2011) | 10 | A/S, L DLPFC (F3) | 1 mA, 10 min, during task or offline, ref SOA, active/sham | During stim: verbal 2-back followed by 3-back (letters) Pre/post stim: STM (digit span forward) and WM (digit span backward) | Online A-tDCS improved digit span forward by 5.5% as compared to offline A-tDCS and sham. No information regarding online task outcome. |

| Mylius et al. (2012) | 24 | A/C/S, R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 2 mA, 20 min, 15 min before and during task, ref SOA active/ sham | Verbal 2-back Pain percpetion (warm/ cold) | A-tDCS over R DLPFC increased tolerance to heat pain as compared to sham. During C-tDCS over the L DLPFC there were fewer outliers as compared to sham. No significant differences in accuracy (dissociation of analgesic effect from cognitive function). |

| Sandrini et al. (2012) | 27 | Bilateral PPC (P3/P4), LAlRC, LC/RA, S | 1.5 mA, 13 min, active/ sham | Verbal STM (1-back) and WM (2-back) | 1-back: LA/RC tDCS abolished practice- dependent improvement in RT as compared to sham (9% vs. 0.65%). 2- back: LC/RA tDCS abolished practice- dependent improvement in RT (9.8% vs. 0.45%) as compared to sham. No impact on error rates. |

| Meiron and Lavidor (2013) | 41 | A /S, R/L DLPFC | 2 mA, 15 min, during task, ref Cz, active/ sham | Verbal n-back (4 levels of WM load), during and after stim | During online stimulation at highest WM loads males benefited from stim over L DLPFC as compared to sham, while females improved after stim over R DLPFC. No impact on RT. Online accuracy scores at the highest WM level was related to post-tDCS recall. |

| tDCS in general learning and memory | |||||

| Kincses et al. (2004) | 22 | A/C/S, L DLPFC (N= 14) and VI (n = 8) | 1 mA, 10 min, 5 min before and during learning, ref Cz, active/sham, | Probabilistic classification learning | A-tDCS over L DLPFC improved learning compared to sham. No effect after C-stim or stim over V1. |

| Marshall et al. (2004) | 30 (males) | Bilateral RA/LA DLPFC (F3/F4) | 0.26 mA/cm2, intermittent on/off 15 s over 30 min, during sleep, active/ sham | Declarative and procedural learning (paired associate word lists and mirror tracing), PANAS/ EWL (mood) | Bilateral anodal tDCS during sleep enhanced word retention compared to sham (35.7 vs. 34.5). No impact when applied during wakefulness and no impact on procedural memory. After active but not sham tDCS positive affect decreased less and feelings of depression decreased. |

| Vines et al. (2006) | 11 | C/S, L SMG (TP3), R SMG (control) | 1.2 mA, 20 min, offline, ref SOA, active/sham/control | Pitch matching (6/7 tones) | C-tDCS to L SMG affected short-term pitch memory performance (9%) compared to R SMG and sham. |

| Elmer et al. (2009) | 20 | A/C/S, R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 1.5 mA, 5 min, during learning, ref mastoid, active/sham | Verbal LTM (VLMT) | C-tDCS to L DLPFC decreased number of words recalled after 25 min compared to sham (12%). No effects on long-term retrieval were found. |

| Boggio et al. (2009) | 30 | Bilateral ATL (T3/T4), (LA/RC), unilateral ATL (LA/RC enlarged electrode), S | 2 mA, 10 min, during encoding and retrieval, active/ sham | False memory (within word categories) | Bilateral and unilateral tDCS reduced false memories (73%) compared to sham. Bilateral tDCS decreased the number of false memories compared to unilateral stim (~1 vs. ~ 2 errors) and compared to sham (~1 vs. ~3.7 errors). |

| Kirov et al. (2009) | 28 | Bilateral RA/LA, DLPFC (F3/F4) | Five 5 min epochs of transcranial slow oscillation stimulation (tSOS, 0.75 Hz), 1 min ISI, 0.517 mA/cm2, ref mastoid, active/sham | Verbal and non-verbal paired association, verbal memory (VLMT), number list learning, procedural memory (mirror tracing, finger sequence tapping), control tasks | TSOS during wakefulness induced a local increase in endogenous EEG slow oscillations (0.4-1.2 Hz) and a widespread increase in EEG theta and beta activity. TSOS during learning improved verbal encoding, but not consolidation as assessed 7 h after learning. |

| Clark et al. (2012) | 96 (divided in diff. stim groups) | Exp. 1–3: A, R inferior PFC (F10) Exp. 4: A, R PC (P4) | 0.6 mA or 2 mA, 30 min, during learning, ref arm, active/control (0.1 mA) | Detection of cues indicative of covert threats | Exp. 1–3: A-tDCS at 2 mA over R inferior PFC improved threat detection sign. more (26.6%) as compared to control (0.1 mA, 14.2%), while forgetting rate over 1 h was similar. Intermediate current strength (0.6 mA) was associated with an intermediate improvement (16.8%). Exp. 4: A-tDCS at 2 mA over R PC improved accuracy sign. more (22.5%) as compared to control (0.1 mA over F10). |

| Chi et al. (2010) | 36 (12 each condition) | Bilateral ATL, LA/RC, RA/LC, S | 2 mA, 13 min, during task, active/sham | Visual memory (geometric shapes) | LC/RA-tDCS resulted in a improved visual memory (accuracy) by 110% as compared to sham. No change after LA/RC-tDCS. |

| Cohen Kadosh et al. (2010) | 15 | Bilateral PC, RA/LC, RC/LA, S | 1 mA, 20 min, 6 days, during learning, active/sham | Numerical learning (pseudo-number paired association), changes assessed by numerical tasks (Stroop, number-to- space task) | 6 days of RA/LC-tDCS improved RT in Stroop compared to sham. RC/LA- tDCS impaired performance compared to sham |

| Penolazzi et al. (2010) | 12 | Bilateral frontotemporal stim between F3/4 and C3/ 4, LA/RC, RA/LC | 1 mA, 20 min, during encodig, active/sham | Visual memory (free recall of images differing in affective arousal and valence) | Bilateral RA/LC-tDCS improved recall of pleasant images compared to unpleasant/neutral images, while bilateral LA/RC-tDCS improved recall of unpleasant images compared to pleasant and neutral images. |

| Javadi et al. (2012) | 13 | A/C, L DLPFC (F3) | 1.5 mA, 1.6 sc, during encoding or delay, ref SOA, active/no stim | Word memorization | A-tDCS during encoding improved accuracy and RT compared to late A-tDCS or no tDCS. C-tDCS during encoding impaired accuracy and RT compared to late C-tDCS or no tDCS. Stim during delay had no effect. |

| Javadi and Walsh (2012) | 32 | A/C/S, L DLPFC (F3), M1 (C3, control) | 1.5 mA, 20 s A, 30 s C, during encoding or recognition, ref SOA, active/sham | Word memorization | During encoding A-tDCS over DLPFC improved accuracy, while C-tDCS impaired accuracy compared to sham. M1-tDCS had no impact. During recognition C-tDCS impaired recognition compared to sham, while A-tDCS showed a trend towards improvement. |

| Hammer et al. (2011) | 36 (A/S=18, C/S=18) | A/C/S, L DLPFC (F3) | 1 mA, 30 min, 10 min before and during learning, ref SOA, active/sham | Errorless/errorfull learning (word stem completion) | C-tDCS impaired encoding and retrieval after errorful learning compared to errorless learning and sham. No impact of anodal stimulation. |

| Bullard et al. (2011) | 34 (control = 14, early = 11, late = 9) | A, R Inferior PFC (F8) | 2 mA, 30 min, early/ late during learning, ref arm, active/ control (0.1 mA) | Detection of cues indicative of covert threats | A-tDCS (2 mA) improved threat detection compared to control (0.1 mA). A-tDCS was more effective when applied during early learning. |

| Marshall et al. (2011) | 16 | Bilateral RA/LA, DLPFC, (F3, F4) | Theta-tDCS at 5 Hz, 0.517 mA/cm2, 5 min, 1 min ISI, during REM or non- REM sleep, ref mastoid, active/sham | Verbal paired association, procedural memory (mirror tracing, finger sequence tapping), mood (PANAS) | Theta-tDCS during non-REM impaired consolidation of verbal memory compared to sham. No effect on consolidation in procedural memory. Stim during REM led to an increase of negative affect. |

| Jacobson et al. (2012) | 24 | Bilateral L IPS/SPL (P3), R IPL (P6), LA/ RC, RA/LC (control) | 1 mA, 10 min, active/ control stim/control group | Verbal memory (discrimination of familiar/unfamiliar words) | LA/RC-tDCS improved accuracy, but not RT as compared to control stim. No effect after LC/RA-tDCS. |

| TMS and tDCS in memory studies with elderly subjects | |||||

| Rossi et al. (2004) | 66 (<45 and >50 y) | R/L DLPFC (F3/F4) | 500 ms of 20 Hz at 90% rMT, during encoding and retrieval, active/ sham/baseline | Visuospatial memory (old/new discrimination of images) | Stim over R DLPFC in younger subjects interfered with retrieval more than stim over L DLPFC. This asymmetrical effect dissipated with age as indicated by bilateral interference effects on recognition. Stim of left DLPFC during encoding had a disruptive effect on all subjects which would not comply with the HAROLD model. |

| Solé-Padullés et al. (2006) | 39 (>50 y with 1+ y memory complaints) | Bilateral R/L DLPFC combined with baseline and post- TMS fMRI | 10 trains of 10 s rTMS at 5 Hz, ITI 30 s, 80% rMT, offline, active/sham | Face–name association | Stim improved associative memory compared to sham (rate of change: 1.60 vs. -0.63). TMS led to an increase in activation of the right IFG and MFG and occipital areas. |

| Manenti et al. (2011) | 31 (60–81 y), HP and LP | R/L DLPFC | 450 ms of 20 Hz rTMS (ISI 7–8 s), total of 640 pulses, 90% rMT, during encoding or retrieval, active/ sham/baseline | Verbal memory (associated/non- associated word pairs) | The high-performing (HP) group performed better in the experimental task than the low-performing group (LP) (92.0% vs. 78.9%). Stim over L DLPFC affected accuracy more during encoding than during retrieval, but only for unrelated word-pairs in the LP group. No significant differences in RT. Asymmetry as predicted by the HERA model was observed only in LP. |

| Flöel et al. (2012) | 20 (50–80 y, mean 62 y) | A, R TPC | 1 mA, 20 min, during learning, active/ sham | Object location learning, immediate and delayed (1 week later) free-recall | Anodal stim improved delayed correct free-recall responses compared to sham (24% vs. 8.5%), but not immediate recall (34% vs. 28.8%). No significant differences in RT. |

| TMS and tDCS in memory studies with Alzheimer’s patients | |||||

| Cotelli et al. (2006) | 15 | R/L DLPFC (btw F3/F4 and F/7/F8), 1 session | 600 ms of 20 Hz TMS at 90% rMT, during encoding, active/ sham | Visuoverbal object and action naming | Stimulation over L and R DLPFC improved accuracy in action naming as compared to sham stimulation. Object naming did not improve significantly. |

| Cotelli et al. (2008) | 24 | R/L DLPFC, 1 session | 500 ms of 20 Hz TMS at 90% rMT, during encoding, active/ sham | Visuoverbal object and action naming | Stimulation over L and R DLPFC improved accuracy in action naming but not object naming as compared to sham stimulation in the mild AD group. Improved naming accuracy for both classes of stimuli was only found in moderate-to-severely impaired patients. |

| Ferrucci et al. (2008) | 10 | A/C/S, bilateral TPC (LA/RA, LC/RC, S), 1 session per condition | 1.5 mA, 15 min, offline, active/sham/baseline | Verbal memory and visual attention | A-tDCS improved accuracy, while C-tDCS decreased performance as compared to baseline. No impact on visual attention. |

| Boggio et al. (2009) | 10 | A/S, L DLPFC (F3), L temporal cortex (T7) | 2 mA, 30 min, A/S, during task, ref SOA, active/sham | Visual STM, WM (digit span backward), Stroop | Accuracy in visual memory improved during A-tDCS over L DLPFC (18%) and temporal cortex (14%) as compared to sham. No effect on WM and Stroop. |

| Cotell et al. (2011) | 10 | L DLPFC, 20 sessions without training vs. 10 sessions placebo | 25 min, 2 s of 20 Hz (ITI 28 s) at 100% rMT, offline, active/sham/baseline | Various tests for memory, executive functions, and language | Improvement of auditory sentence comprehension as compared to baseline and placebo training; no effect on other cognitive or langauge functions. |

| Bentwich et al. (2011) | 8 | 6 regions, 3 per day (Broca, Wernicke, R DLPFC and R-pSAC, L-pSAC, l-DLPFC), (30 sessions with training) | 20 2-s trains of 10 Hz per area (=1200 pulses per day), 90% MT (frontal areas), 110% MT (other areas), active/ baseline | Training tasks: attention, memory, language | ADAS-cog improved by approx. 4 points after training and was maintained at 4.5 months follow-up. CGIC improved by 1.0 and 1.6 points, respectively. MMSE, ADAS-ADL, Hamilton improved, but not significantly. No change in NPI. |

| Boggio et al. (2012) | 15 | A/S, bilateral (RA/LA) temporal cortex (T3/ T4), 5 sessions | 30 min, 2 mA, ref deltoid, offline, active/sham | Visual STM, visual attention, MMSE, ADAS-Cog | A-tDCS improved memory performance by 8.99% from baseline compared to sham (−2.62%). No impact on visual attention or other cognitive measures. |

| Haffen et al. (2011) | 1 | L DLPFC, 10 sessions | 20 min of 5-s trains of 10 Hz (ITI 25 s), 100% rMT, offline, active | Verbal memory (Memory Impairment Screen, free and cued recall), Isaacs Set Test, TMT, picture naming, copying, MMSE | Stimulation improved episodic memory task performance and speed performance. Improvements were still seen 1 month later, however scores returned to baseline by 5 months. ADL improvements reported by wife. |

| Ahmed et al. (2012) | 45 | R/L DLPFC, 5 sessions without training | Group 1: ~10 min of 5-s trains of 20 Hz (ITI 25 s), 90% rMT per DLPFC Group 2: ~ 16 min of 1 Hz rTMS, 100% rMT, ~16 min per DLPFC (2000 p) | MMSE, IADL, GDS | Mild to moderate AD patients (20 Hz) showed improved scores on all rating scales as compared to the 1-Hz and sham groups. Although improvements were present at 1 month, scores returned to near baseline level by 3 months. |

| TMS and tDCS in memory studies with Parkinson’s patients | |||||

| Boggio et al. (2005) | 25 (PD & depression) | L DLPFC, 10 sessions without training | 40 trains of 5 s of 15 Hz, 110% rMT and fluoxetine (20 mg/day), offline, active/sham/baseline | NP (TMT, WCST, Stroop, HVOT, CPM, WM): before treatment, after 2 and 8 weeks | Both the fluoxetine and rTMS groups showed significant improvement in Stroop (colored words), Hooper, and WCST (perseverative errors), and in depression rates. No significant effects on other cognitive functions. |

| Boggio et al. (2006) | 18 | A/S, L DLPFC, M1 (control), 1 session per protocol | 20 min, 1 or 2 mA, 20 min, during task, ref SOA, active/ sham/control | Verbal 3-back | Accuracy in 3-back task after stimulation with 2 mA (20.1%) as well as error frequency (35.3%) improved significantly more as compared to stim with 1 mA, stim over M1, or baseline. |

| TMS and tDCS in memory studies with stroke patients | |||||

| Jo et al. (2009) | 10 (RH stroke), 1–4 months poststroke | A/S, L DLPFC (F3), 1 to session per protocol | 30 min of 2 mA, online (25 min after starting stimulation), ref SOA, active/sham/ baseline | Verbal 2-back before and at 25 min tDCS onset | A-tDCS improved recognition accuracy as compared to sham. No impact on RT. |

A, C, S, anodal, cathodal, sham; ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale; aMT, active motor threshold; ATL, anterior temporal lobe; BA, Brodmann’s area; BBR, brain-behavior relationship; Cb, cerebellum; CGIC, Clinical Global Impression of Change; CPM, colored progressive matrices; cTBS, continuous theta-burst stimulation; Cz, vertex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; DMS, delayed match-to-sample; DMPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; DR, discrimination rate; EF, executive functions; ERP, event-related potential; Exp., experiment; FEF, frontal eye fields; FL, frontal lobe; fO, frontal operculum; Fz, frontal midline; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HF, high frequency; HVOT, Hooper Visual Organization Test; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; IFJ, inferior frontal junction; IPL, inferior parietal lobule; IPS, intraparietal sulcus; ITI, intertrain interval; L, left; LA/RA, left anodal/right anodal; LC/RC, left cathodal/ right cathodal; LF, low frequency; LH, left hemisphere; LOC, lateral occipital cortex; M1, primary motor cortex; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; MSO, maximum stimulator output; NP, neuropsychological; NPI, neuropsychiatric inventory; OC, occipital cortex; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; p, pulse; PANAS, positive and negative symptoms scale; PC, parietal cortex; PCG, postcentral gyrus; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PL, parietal lobule; PM, prospective memory; PMC, premotor cortex; PPC, posterior parietal cortex; ppTMS, paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation; R, right; RBMT, Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test; rCBF, regional cerebral blood flow; ref, reference; RH, right hemisphere; rMT, resting motor threshold; R-pSAC and L-pSAC, right and left parietal somatosensory association cortex; RT, reaction time; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; sign., significant; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; SOA, supraorbital area; sp, single pulse; SPL, superior parietal lobule; stim, stimulation; STM, short-term memory; T, tesla; TL, temporal lobe; TMT, trail making test; TPC, temporoparietal cortex; tRNS, transcranial random noise stimulation; TSOS, transcranial slow oscillation stimulation; VAT, visual attention task; VLPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; VPFC, ventral prefrontal cortex; VFT, verbal fluency test; VRT, visual recognition task; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WM, working memory; y, years.

Despite study variations, the growing body of research summarized in Table 55.1 offers valuable insights into human learning and memory neurobiology, highlighting NBS’s power in cognitive neuroscience.

Short-Term Memory and the Role of Processing Segregation

Prefrontal areas are crucial for STM. NBS studies help clarify information processing streams: domain-specific segregation (spatial, object, verbal processing) versus processing segregation (encoding, maintenance, storage).

Processing Segregation in STM

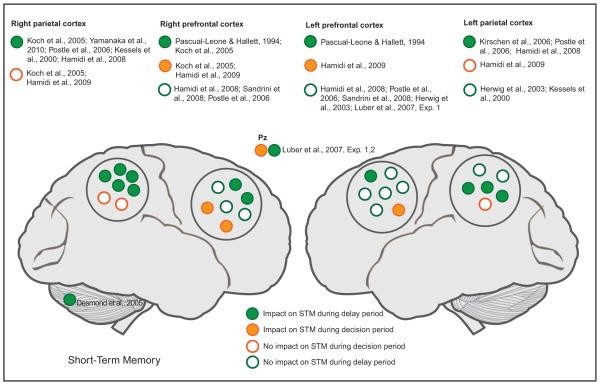

Most studies investigating processing segregation use delayed match-to-sample tasks, applying stimulation during the delay or decision period (Fig. 55.2). High-frequency TMS over the parietal cortex during the delay period can enhance STM (Kessels et al., 2000; Kirschen et al., 2006; Luber et al., 2007; Yamanaka et al., 2010), although some studies report impairment (Koch et al., 2005; Postle et al., 2006). These effects appear specific to the delay period, as parietal TMS during the decision phase has not impacted STM (Luber et al., 2007; Hamidi et al., 2009). DLPFC’s role during the delay phase is less clear. Some TMS studies support DLPFC involvement (Pascual-Leone and Hallett, 1994; Koch et al., 2005), while others find no effect of DLPFC stimulation during delay (Herwig et al., 2003; Postle et al., 2006; Hamidi et al., 2008; Sandrini et al., 2008). Conversely, high-frequency TMS over the DLPFC during the decision period impairs STM (Koch et al., 2005; Hamidi et al., 2009). These findings suggest a dissociation between parietal and prefrontal areas, with parietal regions primarily involved in delay and prefrontal regions in decision phases, supporting a posteroanterior temporal gradient in memory processing. Chronometric TMS designs can further test these notions.

Fig. 55.2.

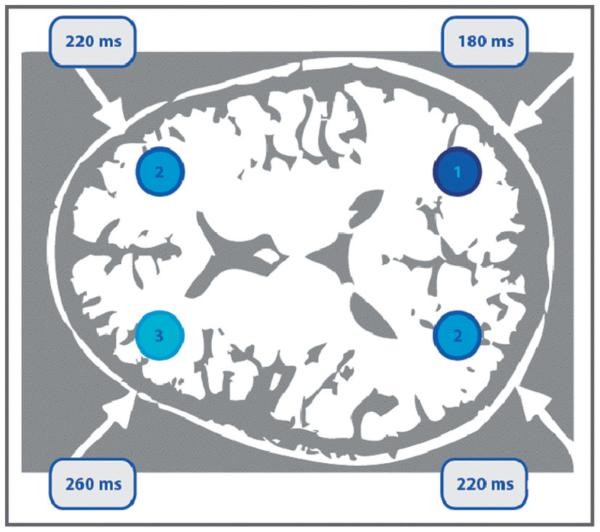

Mottaghy et al. (2003a) conducted a chronometric experiment (Fig. 55.3) on verbal WM, using single-pulse TMS to explore the temporal dynamics of parietal and DLPFC involvement in verbal WM. TMS was applied at 10 time points during the delay period of a 2-back verbal WM task, using neuronavigation for precise targeting. A choice reaction task was used as a control. TMS interference with accuracy was earlier in parietal cortex than PFC, and earlier in the right than left hemisphere, suggesting posterior-to-anterior information flow, converging in the left PFC. Reaction time interference occurred after 180 ms with left PFC stimulation. These effects were task-specific, not seen in the control task. Hamidi et al. (2009) also examined right and left DLPFC roles in recall and recognition, finding right DLPFC stimulation impaired recall accuracy but enhanced recognition accuracy, while left DLPFC stimulation impaired recognition. TMS, in repetitive and chronometric designs, offers valuable insights into STM subprocess functional segregation.

Fig. 55.3.

Domain-Specific Segregation in STM

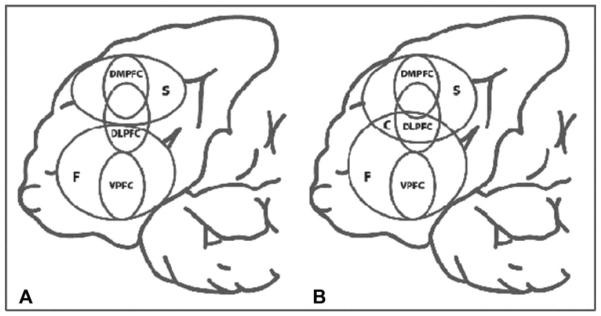

Mottaghy et al. (2002b) showed that functional and modality-specific segregation are not mutually exclusive (Fig. 55.4). They used low-frequency rTMS to disrupt left dorsomedial PFC (DMPFC), DLPFC, or ventral PFC (VPFC) before spatial or nonspatial (face recognition) delayed-response tasks. DMPFC rTMS impaired spatial task performance, while VPFC rTMS impaired nonspatial performance. DLPFC disruption affected both. This reveals task-related segregation along prefrontal structures. Recent studies confirm TMS’s utility in supporting modality-specific segregation. Soto et al. (2012) combined fMRI and rTMS to show verbal and nonverbal memories interact independently with attention: rTMS to the superior frontal gyrus disrupted STM effects from colored shapes, and rTMS to the lateral occipital cortex disrupted effects from written words. Morgan et al. (2013) used TMS to reveal neural substrates for integrating segregated STM features, finding continuous TBS (cTBS) over the right parietal cortex or left inferior frontal gyrus selectively impaired STM for feature combinations, but not single features. Frontal-parietal coupling is critical for binding modality-specific processes.

Fig. 55.4.

Frontoparietal Binding in STM

Frontoparietal interactions are dynamic in memory formation and maintenance. NBS, especially TMS-MRI or TMS-EEG, offers critical insights.

In motor learning, frontoparietal interactions are important early on, as shown by TMS-EEG (Karabanov et al., 2012). In nonmotor domains, a TMS-fMRI study (Feredoes et al., 2011) showed DLPFC’s STM contribution is dynamic, depending on distractors. DLPFC changes communication with posterior regions in the presence of distractors to support maintenance. tDCS studies support DLPFC’s role in STM with distractors (Gladwin et al., 2012; Meiron and Lavidor, 2013). Zanto et al. (2011) combined EEG with 1-Hz rTMS to the right inferior frontal junction, finding TMS diminished EEG patterns in posterior electrodes associated with task-relevant/irrelevant stimulus distinction, predicting STM accuracy decrease. Stronger frontoposterior connectivity correlated with greater disruption. Higo et al. (2011) combined offline TMS over the frontal junction with fMRI, also observing TMS-induced decreases in posterior regions depending on task relevance. The inferior frontal junction may control the link between early attention and STM performance, regulating posterior brain area activity levels based on relevance.

Frontal-posterior area interaction during delay may secure information maintenance, especially against distractors. These processes may relate to regulating and reactivating encoding-active patterns. Frontal areas might recruit neuronal assemblies and regulate posterior area activity to protect and maintain information, with activations strongest early in the delay period, gradually decreasing.

Cerebellum and Sensory Cortex in STM

Beyond frontal and parietal areas, the cerebellum may also be involved in STM. Desmond et al. (2005) found increased reaction time, but no accuracy change, in the Sternberg task with single-pulse TMS over the right superior cerebellum during the delay phase. A tDCS study also found cerebellar tDCS abolished practice-dependent reaction time improvements in a Sternberg task (Ferrucci et al., 2008).

Sensory processing areas are also believed to contribute to sensory STM, guided by attention. TMS studies show visual cortex involvement in visual STM and WM (Postle et al., 2006). TMS to the visual cortex during STM delay decreases accuracy in the targeted visual field for high memory loads (Van de Ven et al., 2012) or memory scanning rates (Beckers and Hömberg, 1991). TMS effects vary if applied at the beginning (inhibitory) or end (facilitatory) of the delay period in visual STM and imagery (Cattaneo et al., 2009), demonstrating state-dependency TMS designs (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2008). TMS may preferentially activate neurons not involved in encoding, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio of memory traces and impairing behavior.

In tactile STM, TMS over the middle frontal gyrus (MFG) during early maintenance decreased reaction time, even with distractors (Hannula et al., 2010). A follow-up showed this improvement occurred only with tactile, not visual, interference (Savolainen et al., 2011).

These findings (e.g., Silvanto and Cattaneo, 2010) suggest sensory brain areas in modality-specific perceptual processing contribute to STM formation and maintenance through interaction with attention. TMS can help elaborate memory process chronology and state-dependent process contributions.

Working Memory: Domain vs. Process Specificity

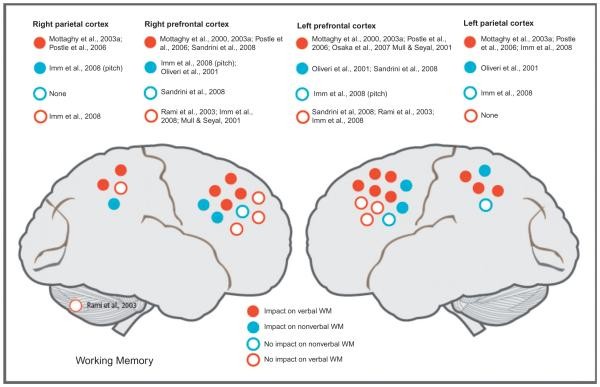

WM has been increasingly studied with NBS. Similar to STM, studies explore DLPFC and parietal area roles, investigating domain- or process-specific information processing (Fig. 55.5). Some studies also examine if STM-active areas are also active in WM tasks.

Fig. 55.5.

Verbal and Nonverbal WM in DLPFC

Building on Mottaghy et al. (2000), most researchers find impaired verbal WM after left DLPFC stimulation (Mull and Seyal, 2001; Mottaghy et al., 2000, 2003a; Postle et al., 2006; Osaka et al., 2007) and right DLPFC stimulation (Mottaghy et al., 2003a; Postle et al., 2006; Sandrini et al., 2008). However, some studies found no such effects (Mull and Seyal, 2001; Rami et al., 2003; Imm et al., 2008; Sandrini et al., 2008).

DLPFC’s role in nonverbal WM is less studied (Oliveri et al., 2001; Imm et al., 2008; Sandrini et al., 2008). Sandrini et al. (2008) investigated domain- and process-specific DLPFC contributions, using identical stimuli (letters in spatial locations) in 1-back (STM) and 2-back (WM) tasks, and 2-back tasks with stimuli from one or both domains. Short 10-Hz rTMS trains were applied at the end of the delay. Interference occurred only in the 2-back task, and only with stimuli from both domains. Letter task performance was impaired by right DLPFC rTMS, while location task performance was impaired by left DLPFC rTMS. They interpreted this as interference with control mechanisms (central executive) suppressing task-irrelevant information, similar to the protection of STM contents (Feredoes et al., 2011; Higo et al., 2011; Zanto et al., 2011), where frontal-posterior interaction during delay secures information maintenance, especially with distractors.

Further experiments dissect DLPFC’s WM role to distinguish domain- vs. process-specific models and examine DLPFC interactions with other areas. TMS combined with brain imaging is valuable here. Mottaghy et al. (2000) found verbal WM (2-back) performance diminished after rTMS to both left and right DLPFC. TMS-PET showed rTMS-altered WM performance was linked to reduced regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) at the stimulation site and distant areas. A follow-up TMS-PET study (Mottaghy et al., 2003b) showed a negative correlation between left DLPFC rCBF and WM performance at baseline (no TMS). rTMS to left or right DLPFC disrupted WM, but with different network impacts. Left DLPFC rTMS changed rCBF in the targeted left DLPFC and contralateral right PFC, while right DLPFC rTMS caused more distributed changes involving bilateral prefrontal and parietal areas (Fig. 55.6B). Behavioral consequences of rTMS were always linked to left DLPFC rCBF impact, regardless of stimulation side. This highlights rTMS to different network nodes can have differential network impacts, network dynamics are modified by behavior, and brain stimulation can affect behavior by disrupting computations in the targeted region or via trans-synaptic network impact. This illustrates the power of TMS-imaging integration for exploring brain-behavior causal relations (Fig. 55.6A). A later chronometric study (Mottaghy et al., 2003a) using single-pulse TMS at different times after stimulus presentation showed TMS interfered with accuracy earlier in parietal than PFC, and earlier in right than left hemisphere, indicating posterior-to-anterior information flow converging in the left PFC. These studies show both hemispheres contribute to WM, but left PFC computation is critical for verbal WM.

Fig. 55.6.

DLPFC involvement, irrespective of stimulus modality, is shown in a bilateral single-pulse stimulation study during a 2-back task (Oliveri et al., 2001). Early temporal stimulation (300 ms) increased reaction time for object WM, while early parietal and late superior frontal gyrus stimulation (600 ms) increased reaction time for spatial WM. Late DLPFC stimulation interfered with both tasks, affecting both reaction time and accuracy. These relate to dorsal (“where”) and ventral (“what”) pathways and parietotemporal-to-frontal information flow. DLPFC may be bilaterally involved in verbal WM and active regardless of stimulus material, unlike other prefrontal regions that may be segregated (e.g., Mottaghy et al., 2002b). Posterior area segregation may be easier to pinpoint, consistent with both hemispheres being involved in spatial and object WM (Smith and Jonides, 1997). Research suggests a process-specific model for DLPFC, while other prefrontal/parietal areas may be modality-based. WM operations relying on DLPFC, like selective attention and executive processes (e.g., inhibiting task-irrelevant stimuli), may be modality-independent (Smith and Jonides, 1999) and play roles in both STM and WM. TMS combined with fMRI and EEG can further disentangle DLPFC and other prefrontal/parietal area interactions in WM.

Prospective Memory and Executive Functions

Prospective memory is linked to other memory components (Fig. 55.1), making process isolation difficult, possibly explaining limited NBS studies. Basso et al. (2010) investigated if verbal WM and prospective memory share processes. Higher prospective memory demand interfered with WM only at higher loads, while WM activity did not affect prospective memory performance, suggesting separate systems. TMS to DLPFC increased prospective memory error rates, with marginal WM effects, supporting distinct systems, though prospective memory may require resources, including WM resources, and thus be more TMS-disruptible. More complex TMS designs are needed to explore this further.

Costa et al. (2011) investigated cTBS effects on prospective memory (80% active motor threshold). Stimulation over left Brodmann area (BA) 10 (frontal pole) impaired accuracy compared to Cz stimulation. No significant difference was found after cTBS over left BA46 (DLPFC) and Cz, suggesting left BA10 is important for prospective memory, consistent with neuroimaging (Koechlin et al., 1999). Costa et al.’s innovative study highlights the need for separate empirical demonstrations of brain stimulation impact on brain function and behavior in NBS memory studies.

Encoding, Consolidation, and Retrieval: PFC’s Role

rTMS during the encoding phase supports PFC’s critical role. Left DLPFC stimulation during encoding affects verbal (Grafman et al., 1994; Rami et al., 2003; Sandrini et al., 2003; Flöel et al., 2004; Skrdlantová et al., 2005; Blanchet et al., 2010; Gagnon et al., 2010, 2011) and nonverbal memory (Rossi et al., 2001, 2004; Blanchet et al., 2010; Gagnon et al., 2010, 2011). Some studies report memory impact after right frontal area stimulation during encoding of verbal (Grafman et al., 1994; Sandrini et al., 2003; Kahn et al., 2005; Blanchet et al., 2010; Machizawa et al., 2010) or nonverbal memory (Epstein et al., 2002; Flöel et al., 2004; Blanchet et al., 2010). Some found no right frontal cortex stimulation effects (Rami et al., 2003; Köhler et al., 2004). No effects were found after parietal (Köhler et al., 2004; Rossi et al., 2006) or occipital cortex stimulation (Grafman et al., 1994), with only one study reporting impairment after temporal cortex stimulation (Grafman et al., 1994).

Fewer studies applied TMS during the retrieval phase. Right DLPFC stimulation during retrieval impacts both verbal (Sandrini et al., 2003; Gagnon et al., 2010, 2011) and nonverbal memory (Rossi et al., 2001, 2004; Gagnon et al., 2010, 2011). No studies report left hemisphere retrieval stimulation effects.