Calculus. The very word can evoke a mix of fascination and fear. For many, it represents the pinnacle of mathematical complexity, a subject both beautiful in its elegance and agonizing in its traditional educational approach. I, too, have experienced this love/hate relationship. Calculus beautifully demonstrates the interconnectedness of mathematics, yet often, math education obscures this beauty beneath layers of unnecessary difficulty.

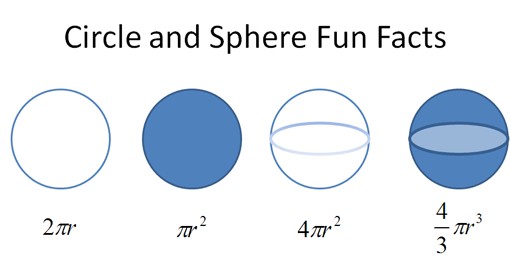

Calculus elegantly links seemingly disparate mathematical concepts, much like Darwin’s Theory of Evolution revolutionized our understanding of biology. Once you grasp evolution, you begin to interpret the natural world through the lens of survival and adaptation. Calculus offers a similar enlightenment in the realm of mathematics. Consider these formulas:

At first glance, they might appear as separate, unrelated facts to be memorized. However, calculus reveals the profound relationships between them. Instead of learning each formula in isolation, calculus allows us to start with a fundamental concept, like the circumference of a circle ($text{circumference} = 2 pi r$), and derive the others. This interconnectedness, a concept the ancient Greeks would have deeply appreciated, is a core strength of calculus.

Unfortunately, the traditional approach to Learning Calculus often embodies the worst aspects of math education. Many calculus lessons are marred by artificial examples, obscure proofs designed to impress rather than illuminate, and a heavy reliance on rote memorization. This approach frequently crushes the very intuition and enthusiasm that are essential for genuine understanding and effective learning calculus.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Math, Art, and Ideas: The Heart of Learning Calculus

My experience has taught me a crucial lesson: the real challenge in math isn’t the mathematics itself, but maintaining motivation. This struggle is often fueled by systemic issues within education:

- An academic environment where educators are often incentivized for research and publication over excellence in teaching.

- Self-perpetuating narratives that paint math as inherently difficult, boring, unpopular, or simply “not for everyone.”

- Textbooks and curricula that prioritize profitability and standardized test scores over fostering genuine insight and a love for the subject.

Paul Lockhart’s essay, ‘A Mathematician’s Lament’ [pdf], eloquently captures this problem and has resonated with many people:

“…if I had to design a mechanism for the express purpose of destroying a child’s natural curiosity and love of pattern-making, I couldn’t possibly do as good a job as is currently being done — I simply wouldn’t have the imagination to come up with the kind of senseless, soul-crushing ideas that constitute contemporary mathematics education.”

Consider how absurd it would be to teach art in a similar fashion. Imagine an art curriculum that begins not with creative expression, but with the dry technicalities of paint chemistry, the physics of light, and the intricate anatomy of the human eye. After twelve years of this, students, now teenagers, might finally be “ready” to start coloring – if their initial spark of artistic curiosity hasn’t been completely extinguished. They would possess the “rigorous, testable” fundamentals, but would they have any genuine appreciation for art?

Poetry offers another insightful parallel. Take this famous quote (a formula of human wisdom):

This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man. — William Shakespeare, HamletThis elegantly encapsulates the essence of “being yourself.” But if this were a math class, we might be compelled to dissect its structure, counting syllables, analyzing iambic pentameter, and diagramming subject-verb-object relationships. We’d miss the point entirely.

Math and poetry, like formulas and art, are fingers pointing at the moon. We must not mistake the finger for the moon itself. Formulas are tools, a means to express profound mathematical truths and unlock deeper understanding.

Somewhere along the way, we’ve lost sight of the fact that mathematics, at its core, is about ideas, not just the rote manipulation of symbols and formulas. Learning calculus should be about grasping these core ideas, not getting bogged down in unnecessary complexity from the outset.

Moving Beyond Memorization in Learning Calculus

“Okay,” you might ask, “if not endless formulas, then what is your approach to learning calculus?”

My aim is not to replicate existing textbooks. If you need immediate answers for an upcoming test, numerous online resources, video lectures, and quick tutorials are readily available.

Instead, my focus is on sharing the fundamental insights of calculus. Equations alone are insufficient. What truly matters are the “aha!” moments – those flashes of understanding that make everything suddenly click into place. These are the keys to effectively learning calculus.

Formal mathematical language is just one method of communication. Diagrams, animations, and clear, straightforward explanations can often convey insights far more effectively than pages filled with dense proofs and abstract notations. For effective learning calculus, intuition and visual understanding are paramount.

Calculus Isn’t Inherent Hard: Rethinking the Approach to Learning

Many believe calculus is inherently difficult. However, I contend that the core ideas of calculus are accessible to anyone. You don’t need to be a professional writer to appreciate Shakespeare, and similarly, you don’t need to be a mathematical prodigy to grasp the essence of calculus.

If you have a solid foundation in algebra and a genuine curiosity about mathematics, learning calculus is within your reach. Historically, reading and writing were skills confined to a select few, trained scribes. Today, these are fundamental skills mastered by most ten-year-olds. Why?

Because of expectation. Expectations profoundly shape what is possible. Therefore, expect that calculus is simply another subject, learnable and understandable. While some may delve into the intricate details and become mathematicians, everyone can appreciate the beauty and power of calculus and expand their minds in the process.

Learning calculus is about how far you want to go. My goal is for everyone to understand the core concepts of calculus and experience that satisfying “whoa” moment of comprehension.

The Essence of Calculus: Patterns Between Equations

So, what exactly is calculus about?

Some define calculus as “the branch of mathematics that deals with limits and the differentiation and integration of functions of one or more variables.” While technically accurate, this definition is hardly illuminating for beginners seeking to understand what learning calculus truly entails.

Here’s a more accessible perspective: Calculus does to algebra what algebra did to arithmetic.

- Arithmetic is concerned with manipulating numbers – addition, multiplication, and so on.

- Algebra identifies patterns and relationships between numbers. The Pythagorean theorem, $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$, describes a famous relationship between the sides of a right triangle. Algebra allows us to find entire sets of numbers; knowing ‘a’ and ‘b’ enables you to determine ‘c’.

- Calculus takes this a step further, discovering patterns and relationships between equations. It reveals how one equation (like circumference $= 2 pi r$) relates to another (like area $= pi r^2$).

With calculus, we can explore a vast array of questions:

- How does an equation change and evolve? How does it accumulate over time?

- When does an equation reach its maximum or minimum value?

- How can we work with variables that are in constant flux, such as heat, motion, or population growth?

- And much, much more!

Algebra and calculus form a powerful problem-solving duo. Calculus helps us derive new equations, and algebra provides the tools to solve them. Like evolutionary theory, learning calculus expands your understanding of how the world functions at a fundamental level.

A Concrete Example: Unveiling the Area of a Circle Through Calculus

Let’s put theory into practice. Suppose we know the formula for the circumference of a circle ($2 pi r$) and want to determine its area. How can calculus help?

Imagine a filled disc as being composed of a series of concentric Russian nesting dolls, each a ring.

Consider two ways to visualize a disc:

- Draw a circle and fill in the interior.

- Draw numerous rings using a thick marker, layering them to fill the disc.

The total “space” (area) occupied should be the same in both cases, right? And how much space does a single ring occupy?

The outermost ring, the largest, has a radius ‘r’ and a circumference of $2 pi r$. As the rings get progressively smaller, their circumference decreases, but they maintain the pattern of $2 pi cdot text{current radius}$. The innermost ring is essentially a point, with virtually no circumference.

Now, here’s where the calculus magic happens. Let’s imagine “unrolling” each of these rings and arranging them side-by-side to form a shape. What emerges?

- We get a series of lines that approximate a jagged triangle. If we use increasingly thinner rings, this jagged triangle becomes smoother and more like a perfect triangle (a concept we will delve into further in future discussions).

- One side of this “ring triangle” is formed by the unrolled smallest ring (essentially zero length), and the opposite side is formed by the unrolled largest ring ($2 pi r$).

- We have rings corresponding to every radius from 0 up to ‘r’. For each possible radius (from 0 to r), we place the corresponding unrolled ring at that position in our triangle.

- The total area of this “ring triangle” is calculated as $frac{1}{2} text{ base} cdot text{height} = frac{1}{2} (r) (2 pi r) = pi r^2$, which is precisely the formula for the area of a circle!

Incredible! The combined area of all the rings equals the area of the triangle, which in turn equals the area of the circle!

This is a simplified illustration, but it highlights a core principle of calculus: we decomposed a disc into smaller components (rings) and rearranged them to reveal a familiar shape (triangle) with a known area. Calculus reveals the intimate relationship between a disc and its constituent rings: a disc is fundamentally composed of an infinite number of rings.

This “big things from little things” approach is a recurring theme throughout calculus. Often, working with infinitesimally small components simplifies complex problems.

The Power of Visual and Relatable Examples in Learning Calculus

Many traditional calculus examples draw heavily from physics. While physics applications are valuable, they can sometimes be abstract and less relatable for learners. How often do you actually encounter a scenario where you know the precise equation for an object’s velocity in everyday life? Probably not very often.

I advocate for starting with physical, visual, and relatable examples because these resonate more deeply with how our brains naturally process information. The ring-and-disc example we explored? You could physically construct this model using pipe cleaners, separate them into rings, and straighten them into a rough triangle to tangibly verify the mathematical relationship. This kind of hands-on, visual confirmation is far more challenging to achieve with abstract velocity equations.

A Word on Rigor: Intuition First in Learning Calculus

I anticipate some mathematicians might raise concerns about the level of “rigor” in this intuitive approach. Let’s briefly address this.

Did you know that the way we currently teach calculus is not how Newton and Leibniz originally discovered it? They relied on intuitive notions of “fluxions” and “infinitesimals.” These intuitive concepts were later replaced by the more formally rigorous framework of limits, driven by the question: “Yes, it may work in practice, but does it hold up in theory?”

While mathematical rigor is essential for advanced study and research, an overemphasis on it too early in the learning process can obscure intuition and hinder understanding. We risk focusing on the “brain chemistry of sugar” instead of simply recognizing it as “Nature’s signal for high energy – eat this!”.

My goal is not to train research mathematicians or deliver a rigorous analysis course. Wouldn’t it be beneficial if everyone grasped calculus at the intuitive level that Newton himself did – enough to fundamentally shift their perspective on the world, as it did for him?

Premature insistence on rigor can discourage students and make learning calculus unnecessarily challenging. Consider the number ‘e’. Technically, ‘e’ is defined using a limit. However, the intuitive understanding of continuous growth is how it was initially discovered. Similarly, the natural logarithm can be defined as an integral, or intuitively understood as the time required for growth. Which explanations are more helpful for beginners embarking on the journey of learning calculus?

Let’s start by “fingerpainting” with intuitive examples, and gradually incorporate the “chemistry” of rigor as understanding deepens. Happy math explorations!

(P.S. For a more visual presentation of these ideas, a kind reader has created an animated PowerPoint slideshow. It’s best viewed in PowerPoint to appreciate the animations. Thank you!)

Note: I’ve developed an entire intuition-first calculus series in the spirit of this article:

https://betterexplained.com/calculus/lesson-1