Visual information processing is crucial for interaction with the environment, and the brain employs distinct neural pathways to manage this complex task. In mammals, two primary cortico-fugal pathways originating from the visual cortex (VC) – the cortico-striatal (CSt) and cortico-tectal (CT) pathways – project to the dorso-medial striatum (dmSt) and the superior colliculus (SC), respectively. Understanding the specific roles of these pathways in visual learning is fundamental to deciphering the mechanisms of neural adaptation. This article delves into the distinct contributions of CSt and CT neurons to visual learning, with a particular focus on Learning Speed in a simple visual detection task performed by mice.

To investigate the roles of these two neuronal populations, researchers trained mice to detect a visual stimulus and respond with a lick for a water reward. The visual stimulus was a drifting grating patch presented in the animal’s left visual field (Figure 1A). Performance was assessed by measuring the first lick latency and the probability of licking during stimulus presentation and blank periods. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analysis was employed to determine the visual specificity of the licking behavior, using the area under the ROC curve (aROC) as a measure of performance. This approach allowed for the detection of visually guided behavior even when hit and false alarm rates were similar, as long as the first lick latency differed between stimulus and blank trials.

Behavioral task schematic and learning curves in mice with intact visual pathways.

(A) Illustration of the behavioral setup where mice learn to lick in response to a visual stimulus (Hit) and withhold licking during blank trials (Correct Rejection – CR). Errors like False Alarms (FA) and Misses are recorded but not punished. (B) Learning progression of an example mouse over training days. Plots show First Lick (FL) latency for stimulus (Hit) and blank trials (FA) across days 1, 5, and 14. Inset graphs display cumulative licking probability and Area under the ROC Curve (aROC), illustrating improved discrimination over time. (C) Schematic of intact cortico-fugal pathways from the visual cortex (VC) to the superior colliculus (SC) and dorsomedial striatum (dmSt). Learning curves (aROC, FL latency, FL variability) averaged across a population of mice (N=8) over 14 days of training. (D) Viral ablation strategy targeting cortico-tectal (CT) neurons, using retroAAV-Cre in Ai14 mice to express td-Tomato and Caspase 3 in CT neurons. Fluorescence microscopy images show reduced fluorescence in layer five of VC in ablated mice compared to controls. Learning curves for CT-ablated mice (N=5) compared to controls (N=7). (E) Similar to (D), but showing viral ablation of cortico-striatal (CSt) neurons (N=5) and learning curves compared to controls. Control data in (D) and (E) is from mice injected with retroAAV-Cre but not AAV-Casp3 (N=7, see Figure 1—figure supplement 6). Data presented as mean ± SEM.

Learning in the visual detection task was characterized by a gradual increase in aROC, a progressive decrease in first lick latency, and reduced trial-to-trial variability in first lick latency on stimulus trials (Figure 1C). Mice were considered to have completed learning when they reached an aROC of at least 0.8 for four consecutive days, typically around the 14th day of training. ROC analysis proved to be a sensitive measure, capturing the temporal dynamics of behavioral responses and providing a reliable metric for stimulus-guided behavior, even before maximizing inhibitory control over the entire response window.

The Role of Cortico-Striatal Neurons in Learning Speed

To determine the contribution of VC neurons projecting to the SC or dmSt to visual learning, researchers selectively ablated CT or CSt neurons, respectively. They used an intersectional viral strategy to express taCaspase3 in specific populations of cortico-fugal neurons. Verification using retrograde tracers confirmed that CT and CSt neurons are largely distinct populations within the VC.

To assess the necessity of CT neurons for visual detection learning, they were selectively ablated in mice prior to training. Surprisingly, ablation of CT neurons had minimal impact on task acquisition compared to control animals (Figure 1D). The learning speed, as indicated by the rate of aROC increase, was similar in CT-ablated and control mice. These results suggested that the cortico-tectal pathway is not crucial for learning this simple visual detection task.

In contrast, when CSt neurons were selectively ablated using a similar viral approach, a striking difference emerged. Mice with CSt ablation showed a significantly slower improvement in visual specificity of licking behavior (Figure 1E). The learning speed was markedly reduced in CSt-ablated mice, as evidenced by a slower increase in aROC over training days. By day 14, CSt-ablated mice exhibited a significantly lower aROC compared to control animals, indicating impaired learning. The latency and variability of first licks on stimulus trials also decreased more slowly in CSt-ablated mice. These findings strongly suggest that cortico-striatal neurons play a critical role in determining the speed of learning in this visual detection task.

Impact of visual cortex lesions on visual learning replicates cortico-striatal ablation effects.

(A) Schematic illustrating surgical ablation of the visual cortex (VC). (B) Coronal sections from a mouse brain showing VC ablation (left) compared to a Paxinos mouse brain atlas section indicating the extent of the lesion (right). (C) Learning curves averaged across VC-lesioned mice (N=8) over 14 days, compared to intact control mice (purple dotted line, from Figure 1C) and CSt-ablated mice (green dotted line, from Figure 1E). (D) Comparison of learning metrics across experimental groups: Population average slope of aROC increase per day (left), spontaneous licking behavior (Inter-Lick Interval – ILI) during inter-trial intervals (middle), and number of trials per training session (right). Data presented as mean ± SEM. VC lesion significantly impairs learning, mirroring the effects of CSt ablation.

To further validate the specific role of CSt neurons, researchers performed complete surgical ablation of the VC. Consistent with the CSt ablation results, VC lesions also led to a significant reduction in learning speed (Figure 2). VC-lesioned mice showed a similar rate of aROC increase as CSt-ablated mice and failed to reach the learning criterion by day 14. This convergence of results from both CSt-specific ablation and complete VC lesion experiments reinforces the conclusion that cortico-striatal pathways are essential for efficient visual learning and, specifically, for determining learning speed.

Learning Speed Versus Ultimate Task Acquisition

The finding that CSt ablation impairs learning speed raises the question of whether it merely slows down learning or completely prevents task acquisition. To address this, mice with CSt ablation and VC-lesioned mice were subjected to extended training. Intriguingly, while control animals reached a performance plateau by day 14, both CSt-ablated and VC-lesioned mice continued to improve with additional training (Figure 3B). By the end of the third week, these animals achieved a similar level of visual specificity (aROC) as control animals at their plateau. This critical finding demonstrates that ablation of CSt neurons does not abolish the capacity to learn the visual detection task; instead, it specifically reduces the speed at which learning occurs. Given sufficient training, the animals can compensate for the absence of CSt neuron function and reach comparable performance levels.

Cortico-striatal neuron ablation specifically reduces learning speed.

(A) Experimental groups and learning curves for intact and CT-ablated mice during the third week of training. Graphs show aROC, First Lick (FL) latency, and FL variability. Intact mice (N=8) show plateaued performance by day 14. (B) Learning curves for VC-lesioned (N=8) and CSt-ablated (N=8) mice, compared to intact controls (purple dotted line from A), during the third week. VC and CSt-ablated mice continue to improve, eventually reaching performance levels comparable to intact mice by day 21. Data is mean ± SEM. This demonstrates that CSt ablation slows, but does not prevent, learning.

Further experiments investigated whether CSt neurons are required for task execution once learning is established. VC lesions were performed on mice that had already mastered the visual detection task. Surprisingly, post-lesion testing revealed no performance impairment (Figure 4A). Mice maintained high visual specificity and similar first lick latencies even after VC ablation. This indicates that while CSt neurons are crucial for the speed of learning, they are not necessary for the execution of the learned task once proficiency is achieved. The neural circuitry supporting task execution appears to shift away from reliance on the cortico-striatal pathway after learning is complete.

Visual cortex lesion after task acquisition does not impair task execution.

(A) Experimental design: VC lesion performed after mice reached proficiency in the visual detection task. Performance was assessed before and 10 days after lesion (no training in between). Example mouse data shows performance pre- and post-VC lesion, including aROC curves and Hit/FA probabilities. (B) Population average aROC for four sessions before and 10 days after VC lesion (N=4 mice). Data is mean ± SEM. Performance in trained animals remains high and unaffected by VC lesion, indicating VC/CSt pathway is not necessary for task execution after learning.

Cortico-Tectal Neurons and Visual Detection Sensitivity

While CT neurons were not found to be essential for learning speed, their role in visual detection itself was investigated further. Given the known involvement of the SC in detecting salient visual stimuli, researchers hypothesized that CT neurons might contribute to visual sensitivity. To test this, they used optogenetic silencing of the VC to acutely and reversibly inhibit VC activity during contrast sensitivity tests.

Optogenetic silencing of VC in trained animals did not impair performance at full stimulus contrast, consistent with the VC lesion experiments in trained mice. However, at lower stimulus contrasts, VC silencing significantly reduced performance, increasing the contrast threshold for detection (Figure 5A). This demonstrated that the VC, likely via CT neurons projecting to the SC, modulates visual sensitivity by lowering the contrast threshold.

Cortico-tectal neuron ablation increases the detection threshold.

(A) Optogenetic silencing of VC. Schematic of VC silencing by activating inhibitory neurons (IN) in VGAT-ChR2-YFP mice. Psychometric function of aROC vs. stimulus contrast under control and VC silencing conditions (N=6 mice). Scatter plot of aROC in control vs. VC silencing, showing stronger impact at lower contrasts. (B) Impact of CT ablation on VC silencing effects. Psychometric functions before and after CT ablation, showing that after CT ablation, VC silencing no longer significantly shifts the contrast detection threshold. Data is mean ± SEM. CT neurons are crucial for VC’s modulation of detection threshold.

To confirm the role of CT neurons in modulating detection sensitivity, they examined the effect of VC silencing after CT ablation. Strikingly, after CT neuron ablation, acute VC silencing no longer led to an increase in the contrast detection threshold (Figure 5B). This critical finding establishes that cortico-tectal neurons are indeed the pathway through which the VC modulates visual detection sensitivity, specifically by enhancing the ability to detect low-contrast stimuli.

Diminishing Role of Cortico-Tectal Pathway with Extensive Training

Finally, researchers investigated whether the role of CT neurons in detection sensitivity is maintained or changes with extended training. They compared the impact of VC silencing on detection sensitivity in animals with different training durations. In early-trained animals, VC silencing caused a substantial increase in the detection threshold. However, in extensively trained animals, VC silencing had a much smaller effect on detection threshold (Figure 6A, B). The impact of VC silencing on detection sensitivity diminished progressively with increased training duration (Figure 6C).

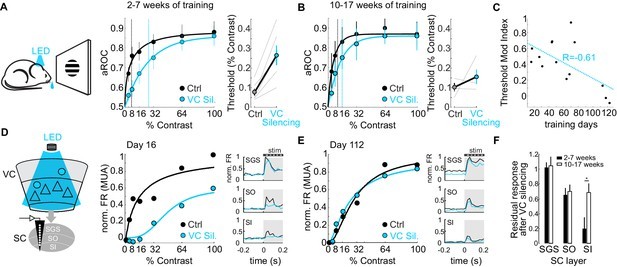

The impact of cortico-tectal neurons diminishes with training.

(A) Psychometric functions and contrast detection thresholds for mice with 2-7 weeks of training, under control and VC silencing conditions. (B) Same as (A) but for mice with 10-17 weeks of training. VC silencing has a smaller effect in extensively trained mice. (C) Modulation index of detection threshold change upon VC silencing plotted against training days, showing inverse correlation. (D, E) Electrophysiological recordings in the Superior Colliculus (SC) during VC silencing in early (D) and late (E) trained mice. Contrast response functions and PSTHs of multi-unit activity (MUA) in SC layers. (F) Population average of normalized evoked activity across SC depth for early and late trained mice, showing reduced VC influence on SC activity with prolonged training. Data is mean ± SEM. The cortico-tectal pathway’s influence on detection sensitivity decreases with extended training.

Electrophysiological recordings in the SC further supported this finding. In early-trained animals, VC silencing significantly reduced visual responses in the SC, particularly in cortical recipient layers. However, in late-trained animals, visual responses in the SC became less dependent on VC input (Figure 6D, E, F). This suggests that with prolonged training, the neural circuits underlying visual detection adapt, reducing the reliance on the cortico-tectal pathway for basic stimulus detection.

Conclusion

This research elucidates the distinct roles of two major cortico-fugal pathways in visual learning and detection. Cortico-striatal neurons are identified as critical determinants of learning speed in a visual detection task, facilitating the rapid acquisition of stimulus-reward associations. However, these neurons are not required for task execution once learning is complete. In contrast, cortico-tectal neurons, projecting to the superior colliculus, play a crucial role in modulating visual detection sensitivity, particularly for low-contrast stimuli. Interestingly, the influence of the cortico-tectal pathway on detection sensitivity diminishes with extensive training, indicating a dynamic shift in neural circuit engagement as learning progresses. These findings provide valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying different aspects of visual learning and adaptation, highlighting the specialized functions and plasticity of distinct cortico-fugal pathways.

References

Brown and Hestrin, 2009

Evans et al., 2018

Faull et al., 1986

Fawcett, 2006

Gray et al., 2010

Hattox and Nelson, 2007

Jones, 1984

Kemp and Powell, 1970

Khibnik et al., 2014

Liang et al., 2015

Lien and Scanziani, 2013

Luppi et al., 1990

Lur et al., 2016

Macmillan and Creelman, 2005

Madisen et al., 2015

Norita et al., 1991

Olsen et al., 2012

Rhoades et al., 1985

Saint-Cyr et al., 1990

Serizawa et al., 1994

Shang et al., 2015

Shang et al., 2018

Swadlow, 1983

Tang and Higley, 2019

Tervo et al., 2016

Wan et al., 1982

Wang and Burkhalter, 2013

Yang et al., 2013

Zingg et al., 2017

[bib92]: