Introduction

The correlation between student attitudes and academic success is well-documented in educational research. This article delves into the impact of two specific pedagogical strategies, Interactive Groups (IGs) and Dialogic Literary Gatherings (DLGs), on shaping students’ attitudes Towards Learning. Drawing upon quantitative data derived from attitude tests, this study presents a novel analysis of how these interactive methodologies foster a more positive disposition in students towards learning.

Attitudes, as defined by Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, Amodio, and Gable [1], are “subjective evaluations ranging from good to bad, stored in memory” [1]. This definition aligns with established social psychology perspectives on attitudes [2]. Prior research firmly establishes a link between students’ attitudes and their academic performance [3,4]. Early studies highlighted the influence of teacher expectations on student achievement, suggesting that educators’ perceptions of student attitudes and behaviors can significantly affect academic outcomes [5]. Molina and colleagues [4], building on Mead’s social construction of identity theory [6], propose that a student’s self-identity profoundly shapes their learning expectations and, consequently, their academic trajectory. This identity formation is inherently a social process.

Mead’s theory [6] posits that the self emerges from social interactions, where individuals internalize the attitudes and expectations projected upon them by others. Identity comprises two elements: the “me,” a socially constructed component reflecting others’ attitudes, and the “I,” the individual’s conscious response to these attitudes. This interplay between the individual and their social environment shapes self-perception. This dynamic can explain why some students develop an identity as “struggling learners,” while others identify as “successful learners,” a phenomenon often referred to as the “Pygmalion effect” [5]. Flecha [7], referencing successful educational actions (SEAs), suggests that when teachers facilitate improved student outcomes, these students, in turn, enhance their self-concept as learners – impacting both their “me” and “I” in Mead’s framework. However, a crucial question remains: does this improvement in self-concept translate into a tangible shift in their attitudes towards learning within the school environment?

Classic research, such as Learning to Work [8], indicates that students with lower academic achievement often exhibit school rejection, manifesting as negative attitudes. These students tend to view school as unengaging and undesirable, displaying resistance and aversion, which correlates with their academic struggles. Bruner later suggested that this negative attitude stems from schools’ failure to meet these students’ (and their families’) expectations [9]. Consequently, students’ identities are shaped in alternative spaces and with different reference points, potentially hindering teachers’ instructional effectiveness. Studies reveal a decline in school interest as these students progress, particularly during the transition from primary to secondary education, with a disengagement from subjects like science and mathematics. Conversely, research has demonstrated that learning initiatives outside traditional classroom settings, such as museum visits or science center explorations, can positively alter these attitudes towards learning [10].

This article examines the influence of two SEAs [7], Interactive Groups and Dialogic Literary Gatherings, on students’ attitudes towards learning. While the positive effects of SEAs on learning outcomes are well-established [11–15], and evidence suggests benefits for classroom coexistence and group cohesion [16,17], the specific impact on students’ attitudes has remained largely unexplored. This study addresses this gap by investigating this crucial dimension of learning, which, as previous research suggests, is vital for understanding the learning process itself and fostering a positive attitude towards learning.

Theoretical Underpinnings

The Interplay of Attitudes and Learning

A fundamental belief in education is the direct relationship between student attitudes and academic achievement. Renaud [18] differentiates between dispositions and attitudes, defining dispositions as more enduring traits and attitudes as tendencies towards learning, or internal states evaluating aspects like “learning math, extracurricular activities, or the general notion of going to school” [18]. Research consistently demonstrates a clear link between attitudes and learning. Renaud [18] cites reviews showing a correlation between attitude and achievement in mathematics [19–21] and science [22]. This relationship tends to strengthen at higher educational levels [22–24].

Ma and Kishor [19] identify self-concept in mathematics, family support, and gender roles in mathematics as key indicators of attitude influencing academic achievement. Their findings highlight self-concept as the most significant correlate. Masgoret and Gardner [23] suggest that motivation is more directly linked to academic achievement than attitude itself. Attitude, however, indirectly influences achievement through motivation. Motivation and self-concept are clearly related, though the causal direction remains unclear: whether motivation fuels positive self-concept or vice versa. Regardless, both motivation and self-concept are positively correlated with academic success; higher levels of both are generally associated with improved academic outcomes, indicating their importance in shaping a student’s approach towards learning.

Symbolic Interactionism: A Framework for Understanding Attitudes

Symbolic interactionism provides a robust theoretical lens for analyzing the relationship between attitudes, motivation, self-concept, and academic achievement. George H. Mead [6], a prominent figure in this theory, emphasizes the social origin of self-concept: “The self is something which has a development; it is not initially there at birth” [6]. Mead introduces the concept of the “generalized other,” defined as “the organized community or social group which gives to the individual his or her unity of self” [6]. He uses the analogy of a baseball team to illustrate this, where each player’s role and actions are defined by the expectations within the team, the “generalized other.” This exemplifies how the self emerges through social processes. Similarly, Vygotsky [25] argued that higher psychological functions develop through social interaction and are subsequently internalized.

Mead states:

It is in the form of the generalized other that the social process influences the behavior of the individuals involved in it and carrying it on, i.e., that the community exercises control over the conduct of its individual members; for it is in this form that the social process or community enters as a determining factor into the individual’s thinking. [6]

This social process involves shared activities and interactions within a group. The classroom serves as a prime example of such a group, comprising teachers and students with defined roles, norms [26], and a shared institutional objective: teaching and learning.

Some research frames this social unit as a “community of practice” [27,28]. Brousseau [29] utilizes the concept of “didactic contract” to analyze the dynamics within a mathematics classroom. He posits a relationship between participants where each actor has specific roles and responsibilities. The teacher is obligated to create conducive learning conditions and recognize student knowledge acquisition, while students are responsible for engaging with these conditions. Brousseau examines the “didactic transposition” of scientific knowledge into teachable content, focusing on identifying epistemological and cognitive obstacles to student learning.

However, research also acknowledges non-cognitive and non-epistemological factors, such as social interactions [16,30,31], influencing academic achievement. As Mead [6] suggested, self-concept arises from internalizing expectations associated with one’s role within a group. A student who consistently participates and answers questions embodies the “good student” role, fulfilling group expectations and reinforcing their identity. The impact of positive or negative expectation projections on students is well-documented [32,33], highlighting the importance of teachers avoiding negative projections to prevent adverse effects like the Pygmalion effect or self-fulfilling prophecies [5].

Despite extensive research on the impact of social interactions and expectations, the specific influence of successful educational actions [7] like Interactive Groups and Dialogic Literary Gatherings on students’ attitudes towards learning remains underexplored. This article addresses this gap, investigating how these SEAs shape students’ disposition towards learning in the classroom.

Successful Educational Actions: Interactive Groups and Dialogic Literary Gatherings

This study investigates the research question within the framework of successful educational actions (SEAs) identified by the European Commission’s INCLUD-ED project [34]. SEAs are defined as school-based interventions demonstrably improving student learning outcomes [7]. This article focuses on two SEAs: Interactive Groups and Dialogic Literary Gatherings, and their influence on attitudes towards learning.

Interactive Groups (IGs)

Interactive Groups (IGs) are a group-based teaching approach where students are divided into small, heterogeneous groups of six or seven, each facilitated by an adult volunteer. Heterogeneity is key, ensuring diverse ability levels, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds within each group. The facilitator encourages dialogic interaction as students work on tasks designed by the teacher. Typically, a classroom is divided into four or five IGs, each assigned a specific task related to the lesson’s subject matter (e.g., mathematics, language arts, science, history). Groups spend fifteen to twenty minutes on each task before rotating to the next, ensuring all students engage with all tasks by the end of the session. In some settings, students rotate, while in others, facilitators move between groups to minimize disruption.

Facilitators are instructed not to provide answers but to encourage students to collaboratively explain and justify their reasoning to group members. The emphasis is on fostering dialogic talk [15], grounded in principles of dialogic learning [35]. Research indicates that dialogic talk enhances academic achievement [15,30,36]. When facilitators prompt students to justify their answers, students must articulate and defend their understanding of the concepts embedded in the tasks, promoting deeper conceptual engagement and communication. This type of interaction, focused on reasoned justification rather than power dynamics, is defined as dialogic talk [30], oriented towards validity claims [37].

Dialogic Literary Gatherings (DLGs)

Dialogic Literary Gatherings (DLGs) involve students and a facilitator (typically the teacher) engaging in shared reading and discussion of classic literature. Students sit in a circle, and the facilitator’s role is to manage participation, not to lead the discussion or offer interpretations. Students volunteer to share their chosen paragraphs and insights. Readings are drawn from classic works by authors like Shakespeare, Cervantes, Kafka, and Tagore [38,39]. Students read assigned pages at home, selecting a paragraph that resonates with them and noting their reasons for choosing it. During the DLG session, students share their selected paragraphs, explaining their significance to the group. The teacher manages turns, ensuring equitable participation and prioritizing less frequent contributors. After each sharing, the floor is opened for questions and discussion, guided by the teacher to maintain focus and relevance.

This process encourages “dialogical reading” [40], based on Bakhtin’s concept of “dialogism” [41]. Bakhtin uses “polyphony” to describe the multiplicity of voices in narrative works, as seen in Dostoevsky’s novels [41]. He argues that every voice is a composite of multiple voices. In education, this translates to knowledge being constructed through internalizing diverse perspectives – from teachers, family, friends, and peers. DLGs recreate this polyphony through dialogues where students contribute their interpretations and understandings of the text. This collaborative approach deepens reading comprehension beyond individual reading, as students incorporate peers’ viewpoints into their own understanding, fostering a richer and more nuanced approach towards learning and literature.

Methodology

The data for this research originates from the SEAs4All–Schools as Learning Communities in Europe project. The dataset is available as supporting data for public access. Six schools across Cyprus, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Spain participated, including five primary schools and one middle/high school. Schools were selected based on their implementation of successful educational actions (SEAs) [7]. Following the implementation of IGs and DLGs, a survey was conducted in three schools to assess the impact on student attitudes and perceptions towards learning. Participants were children aged 7 to 11 from two schools in the United Kingdom and one in Italy. The UK schools were located in contrasting socioeconomic areas: Cambridge (high SES) and Norwich (medium SES), while the Italian school was in a low SES area of Naples. The survey included 418 children: 251 participating in DLGs and 167 in IGs (Table 1).

Table 1. Samples collected in the three schools participating in the survey.

| School 1 (Italy) | n = 168 |

|---|---|

| School 2 (UK) | n = 29 |

| School 3 (UK) | n = 221 |

| Total | n = 418 |

Data collection utilized a modified SAM (Self-Assessment of Motivation) questionnaire, originally developed at the Universities of Leicester and Cambridge, UK. The original 17-item SAM questionnaire, using a 5-point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), was adapted to 12 items based on pilot testing [S1 File].

Children completed paper versions of the questionnaire. Data were then coded, entered into Excel, and analyzed using SPSS (version 25.0). Data cleaning involved univariate descriptive analysis using frequency tables for each item to identify and correct transcription errors by cross-referencing with original paper questionnaires.

Data analysis began with descriptive statistics (mean, median, mode, variance, standard deviation) presented in frequency tables. To investigate the underlying factor structure related to IGs, DLGs, and student attitudes, principal component analysis was employed, as no prior assumptions were made about the relationships. Bartlett’s sphericity test (Χ2) assessed the homoscedasticity across the three school samples to validate the use of factor analysis:

| X2=N-klnSp2-∑i=1kni-1ln(Si2)1+13(k-1)(∑i=1k1ni-1-1N-k) | (1) |

|---|

Where k = 3, representing the three school samples. Bartlett’s test was applied separately to DLG and IG participant subsamples. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

| IGs | DLGs | |

|---|---|---|

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.517 | 0.610 |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-square | 30.576 |

| df | 6 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 |

Prior to Bartlett’s test, items #1, #3, #4, and #6 were recoded due to reverse-coded Likert scales. These negatively phrased items (“we learn best when the teacher tells us what to do,” “learning through discussion in class is confusing,” “sometimes, learning in school is boring,” and “I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas”) were recoded to align with the positive directionality of the other items. Responses for these four variables were reversed to ensure consistent scale interpretation across the questionnaire.

Bartlett’s test results for both IGs and DLGs supported the null hypothesis, justifying the use of factor analysis to identify principal components explaining variance in attitudes towards learning. The findings are detailed below.

Ethics Statement

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Community of Research on Excellence for All, University of Barcelona. Informed consent was obtained from families of participating children by the respective schools.

The Ethics Board comprised experts in diverse fields: Dr. Marta Soler (project evaluation, EU research ethics), Dr. Teresa Sordé (project evaluation, Roma studies), Dr. Patricia Melgar (gender violence, gender studies), Dr. Sandra Racionero (data protection, child protection), Dr. Cristina Pulido (communication studies), Dr. Oriol Rios (masculinities, social change), and Dr. Esther Oliver (project evaluation, gender violence).

Results

Students’ Attitudes Towards Learning

The collected data indicate that students participating in IGs and DLGs exhibit generally positive attitudes towards learning. Table 3 shows predominantly positive responses across most items, with 75% to 80% agreement, except for items #3, #4, and #6. This was expected due to the negative phrasing of these items, designed to reverse the positive response trend. However, item #1 responses aligned with the positive trend, contrary to expectations.

Table 3. Valid percent of students’ answers participating in IGs and DLGs.

| Item | Strongly agree | Agree a little | Not Sure | Disagree a little | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1. We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do | 62.1 | 20.0 | 9.9 | 3.9 | 4.2 |

| #2. We learn more when we can express our own ideas | 48.8 | 25.6 | 18.5 | 2.5 | 4.7 |

| #3. Learning through discussion in class is confusing | 19.7 | 20.7 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 26.8 |

| #4. Sometimes learning in school is boring | 23.1 | 18.7 | 7.0 | 10.9 | 40.3 |

| #5. Learning in school is better when we have other adults to work with us | 62.4 | 14.5 | 10.1 | 5.4 | 7.6 |

| #6. I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas | 18.9 | 10.8 | 21.4 | 11.3 | 37.6 |

| #7. I enjoy learning when my friends help me | 65.0 | 13.6 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 6.8 |

| #8. It is good to hear other people’s ideas | 55.9 | 22.4 | 9.0 | 3.7 | 9.0 |

| #9. Helping my friends has helped me to understand things better | 58.0 | 18.7 | 11.9 | 5.3 | 6.1 |

| #10. I am more confident about learning in school than I used to be | 61.8 | 15.4 | 14.0 | 2.5 | 6.4 |

| #11. I like discussing the books we read with the class | 46.9 | 20.3 | 12.1 | 7.3 | 13.6 |

| #12. At home, sometimes we talk about what I have been learning in school | 60.4 | 17.1 | 9.3 | 4.9 | 8.3 |

The positive response to item #1 (“We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do”) might reflect a perceived active teacher role, seemingly inconsistent with the student-centered nature of IGs and DLGs. Conversely, the expected preference for student agency aligns with responses to other items. The affirmation of learning best when teachers direct may indicate response bias due to established classroom norms [26] or a recognition of the teacher’s leadership role.

Table 4 summarizes responses into “agree” and “disagree” categories, highlighting the overall trend.

Table 4. Valid percent of students’ answers participating in IGs and DLGs (Summary).

| Item | Agree | Disagree |

|---|---|---|

| #1. We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do | 82.1 | 8.1 |

| #2. We learn more when we can express our own ideas | 74.4 | 7.2 |

| #3. Learning through discussion in class is confusing | 40.4 | 44.0 |

| #4. Sometimes learning in school is boring | 41.8 | 51.2 |

| #5. Learning in school is better when we have other adults to work with us | 76.9 | 13.0 |

| #6. I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas | 29.7 | 48.9 |

| #7. I enjoy learning when my friends help me | 78.6 | 11.4 |

| #8. It is good to hear other people’s ideas | 78.3 | 12.7 |

| #9. Helping my friends has helped me to understand things better | 76.7 | 11.4 |

| #10. I am more confident about learning in school than I used to be | 77.2 | 8.9 |

| #11. I like discussing the books we read with the class | 67.2 | 20.9 |

| #12. At home, sometimes we talk about what I have been learning in school | 77.5 | 13.2 |

Items #4 and #10 are particularly insightful regarding student attitudes towards learning. Item #4 reveals that approximately half of the students do not find learning boring, suggesting IGs and DLGs make mathematics engaging for them. For children aged 7-11, the fun/boring dichotomy is a strong indicator of attitude.

Item #10 highlights self-confidence, a crucial factor in positive attitudes towards learning [5]. Students with self-belief tend to exhibit more positive dispositions towards learning. The data suggests that participation in IGs or DLGs fosters this self-confidence, with three out of four children reporting increased confidence in their school learning. This is a significant finding, indicating a positive transformation in attitudes towards learning through IGs and DLGs, consistent across the surveyed schools and contexts.

Principal Component Analysis

The KMO test, assessing partial correlations, yielded values of 0.517 (IGs) and 0.610 (DLGs), suggesting (with caution) factor analysis suitability. Bartlett’s sphericity test (null hypothesis: correlation matrix is an identity matrix) yielded significant results (p < 0.001) for both IGs and DLGs, supporting the use of factor analysis.

ANOVA and iterative testing led to two models (IGs and DLGs) explaining over half the variance. Tables 5 and 6 present these results.

Table 5. Total variance explained (students participating in the IGs).

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 1.465 | 36.631 | 36.631 |

| 2 | 1.063 | 26.570 | 63.201 |

| 3 | 0.868 | 21.692 | 84.893 |

| 4 | 0.604 | 15.107 | 100.00 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysisa

aThe only cases used are those in which DLG or IG = IG in the analysis phase

Table 6. Total variance explained (students participating in the DLGs).

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 1.803 | 22.540 | 22.540 |

| 2 | 1.148 | 14.352 | 36.891 |

| 3 | 1.059 | 13.239 | 50.131 |

| 4 | 1.045 | 13.063 | 63.193 |

| 5 | 0.883 | 11.034 | 74.227 |

| 6 | 0.768 | 9.598 | 83.826 |

| 7 | 0.696 | 8.699 | 92.525 |

| 8 | 0.598 | 7.475 | 100.00 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysisa

aThe only cases used are those in which DLG or IG = DLG in the analysis phase

Tables 5 and 6 indicate that the SAM test better explains attitudes towards learning in DLGs (74.227% variance explained by four components) compared to IGs (63.201% variance explained by two components). This suggests the SAM test is more sensitive to attitude variations within DLGs.

Sedimentation graphs visually confirm this. Figure 1 shows a clear inflection from component 2 for IGs, while for DLGs, the inflection starts from component four, suggesting more nuanced attitudinal dimensions in DLGs.

Fig 1. Comparison between the sedimentation graphs corresponding to the analysis of principal components for IGs (image on the left side) and for DLGs (image on the right side).

The component matrix for IGs (Table 7) suggests Factor 1 represents “active peer-support” (item #9 “Helping my friends has helped me to understand things better”) and “active listening” (item #8 “It is good to hear other people’s ideas”). Factor 2 represents “participation” (item #2 “We can learn more when we can express our own ideas”). “Individualism” (item #6 “I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas”) has the lowest explanatory power, indicating the importance of collaboration in IGs. Table 7 shows Factor 1 as the primary variance explainer, with Factors 2, 3, and 4 being less significant.

Table 7. Component matrix for IGsa,b.

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| #9. Helping my friends has helped me to understand things better | 0.733 | -0.225 |

| #2. We can learn more when we can express our own ideas | 0.358 | 0.779 |

| #8. It is good to hear other people’s ideas | 0.804 | 0.160 |

| #6. I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas | 0.392 | -0.616 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysisa,b

a 2 components extracted

b The only cases used are those for which DLG or IG = IG in the analysis phase

For DLGs, the component matrix (Table 8) shows Factor 1 dominated by “positive discussion” (item #11 “I like discussing the books we read with the class”), “self-confidence in school” (item #10 “I am more confident about learning in school than I used to be”), and “participation” (item #2 “We can learn more when we can express our own ideas”). Factor 2 is primarily “teacher-directed learning” (item #1 “We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do”). Factor 3 is “individualism” (item #6 “I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas”), and Factor 4 is “confusion in discussion-based learning” (item #3 “Learning through discussing in class is confusing”).

Table 8. Component matrix for DLGsa,b.

| | Component |

|—|—|—|—|

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| #3. Learning through discussion in class is confusing | -0.068 | -0.327 | 0.467 | 0.604 |

| #11. I like discussing the books we read with the class | 0.667 | -0.056 | 0.070 | -0.396 |

| #1. We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do | 0.189 | 0.782 | 0.154 | -0.130 |

| #2. We learn more when we can express our own ideas | 0.604 | -0.416 | -0.173 | 0.107 |

| #6. I would rather think for myself than hear other people’s ideas | 0.053 | 0.107 | 0.842 | -0.056 |

| #8. It is good to hear other people’s ideas | 0.519 | -0.339 | 0.238 | -0.391 |

| #10. I am more confident about learning in school than I used to be | 0.608 | 0.295 | -0.097 | 0.347 |

| #12. At home, sometimes we talk about what I have been learning in school | 0.558 | 0.196 | -0.088 | 0.467 |

Extraction method: Principal component analysisa,b

a 4 components extracted

b The only cases used are those for which DLG or IG = DLG in the analysis phase

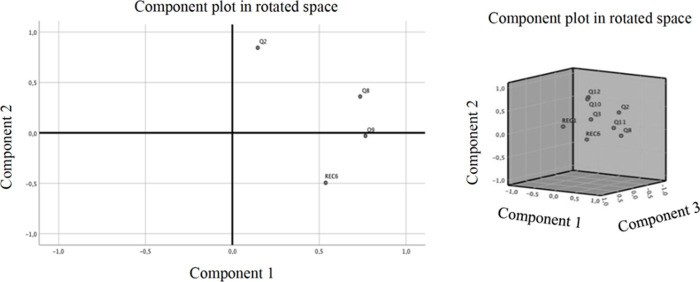

Figure 2 displays rotated component graphs for IGs and DLGs, visually confirming table interpretations. For IGs (left), variables #8 and #9 are primary drivers of Factor 1 variance. For DLGs (right), the 3D component chart shows two distinct variable groupings.

Fig 2. Rotated component graphs for IGs (image on the left side) and for DLGs (image on the right side).

Constructing Attitude Subscales for IGs and DLGs

To refine the understanding of attitudes towards learning in IGs and DLGs, subscales were constructed to identify the most reliable variables.

For IGs, Subscale 1 (Items #1, #7, #10) and Subscale 2 (Items #2, #5, #11) were created. Subscale 1 (Tables 9-11) showed mediocre reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.412), while Subscale 2 (Tables 12-14) demonstrated higher reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.794), suggesting it better captures attitudinal components in IGs. The key difference is Subscale 2’s inclusion of item #5 (“Learning in school is better when we have other adults to work with us”), which showed the highest correlation (0.613) within this subscale (Table 13).

Table 9. Reliability statistics for subscale 1 (IGs).

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| 0.412 | 0.486 | 3 |

Table 11. Item-total statistics for subscale 1 (IGs).

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 8.8261 | 2.332 | 0.381 | 0.18 | 0.095 |

| #7 | 9.087 | 1.174 | 0.291 | 0.1 | 0.391 |

| #10 | 8.3478 | 3.601 | 0.212 | 0.096 | 0.439 |

Table 12. Reliability statistics for subscale 2 (IGs).

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| 0.794 | 0.799 | 3 |

Table 14. Item-total statistics for subscale 2 (IGs).

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | 8.7391 | 2.929 | 0.602 | 0.387 | 0.769 |

| #5 | 8.913 | 2.992 | 0.722 | 0.526 | 0.626 |

| #11 | 8.6087 | 3.613 | 0.604 | 0.406 | 0.757 |

Table 13. Inter-item correlation matrix for subscale 2 (IGs).

| #2 | #5 | #11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | 1 | 0.613 | 0.467 |

| #5 | 0.613 | 1 | 0.628 |

| #11 | 0.467 | 0.628 | 1 |

Table 10. Inter-item correlation matrix for subscale 1 (IGs).

| #1 | #7 | #10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 1 | 0.316 | 0.31 |

| #7 | 0.316 | 1 | 0.092 |

| #10 | 0.31 | 0.092 | 1 |

For DLGs, Subscale 3 (Items #1, #5, #10, #11) and Subscale 4 (Items #2, #7, #8, #9) were constructed. Subscale 3 (Tables 15-17) showed high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.820). Removing item #10 (“self-confidence”) slightly increased reliability to 0.829, suggesting self-confidence might be less central to attitudes towards learning in DLGs. Subscale 3 (Tables 15-17) was more reliable than Subscale 4 (Tables 18-20), which had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.767.

Table 15. Reliability statistics for subscale 3 (DLGs).

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| 0.820 | 0.830 | 4 |

Table 17. Item-total statistics for subscale 3 (DLGs).

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 13.5800 | 6.160 | 0.545 | 0.392 | 0.816 |

| #5 | 13.1400 | 6.032 | 0.796 | 0.659 | 0.727 |

| #10 | 13.3200 | 6.143 | 0.518 | 0.365 | 0.829 |

| #11 | 13.4200 | 4.368 | 0.791 | 0.672 | 0.699 |

Table 18. Reliability statistics for subscale 4 (DLGs).

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| 0.767 | 0.794 | 4 |

Table 20. Item-total statistics for subscale 4 (DLGs).

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | 13.6000 | 4.083 | 0.497 | 0.360 | 0.762 |

| #7 | 13.9600 | 3.123 | 0.501 | 0.312 | 0.752 |

| #8 | 13.9600 | 2.123 | 0.725 | 0.547 | 0.636 |

| #9 | 13.800 | 3.417 | 0.721 | 0.543 | 0.661 |

Table 19. Inter-item correlation matrix for subscale 4 (DLGs).

| #2 | #7 | #8 | #9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #2 | 1 | 0.206 | 0.519 | 0.552 |

| #7 | 0.206 | 1 | 0.516 | 0.474 |

| #8 | 0.519 | 0.516 | 1 | 0.68 |

| #9 | 0.552 | 0.474 | 0.680 | 1 |

Subscale 3’s higher reliability likely stems from including item #11 (“I like discussing the books we read with the class”), which is directly relevant to the DLG context. While Subscale 4 focuses on broader student interaction, it explains less variance than Subscale 3, suggesting the latter is a more robust measure of attitudes towards learning within DLGs.

Table 16. Inter-item correlation matrix for subscale 3 (DLGs).

| #1 | #5 | #10 | #11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 1 | 0.537 | 0.259 | 0.608 |

| #5 | 0.537 | 1 | 0.582 | 0.781 |

| #10 | 0.259 | 0.582 | 1 | 0.528 |

| #11 | 0.608 | 0.781 | 0.528 | 1 |

Discussion and Conclusions

Decades of educational research affirm the significant impact of attitudes on learning [42–46]. Fennema and Sherman [3] highlighted the role of “affective factors” in explaining individual differences in mathematics learning almost fifty years ago [3]. Learning outcomes are demonstrably influenced by student attitudes. School resistance and negative attitudes impede academic progress, while positive attitudes, encompassing motivation and self-concept, correlate with academic success [19]. The Pygmalion effect [5] illustrates how expectations shape student performance and attitudes towards learning.

SEAs [7] like IGs and DLGs, grounded in dialogic learning theory, emphasize transformation. Freire [47] argued that humans are agents of transformation, not mere adaptation, and education should facilitate this. Integrating evidence-based practices, SEAs aim to create genuine learning opportunities. Our data indicates that students in IGs and DLGs exhibit positive attitudes towards learning. Table 4 shows that a significant majority enjoy learning (78.6%) and less than half find it boring (41.8%). The SAM test, validated in prior studies [10,48,49], effectively measures these attitudes. This study provides initial evidence of a positive relationship between SEAs and attitudes towards learning. We can conclude that SEAs are associated with positive student attitudes towards learning, empowering students to transform their learning dispositions.

Social contexts significantly shape attitudes. Empowering environments based on “maximum expectations” [50,51] can reshape attitudes towards learning, especially for students resistant to traditional schooling. In communities where school is undervalued, students face social pressure to resist school norms and values, hindering academic achievement. Symbolic interactionism [6,8] highlights the challenge of counteracting group norms. Identity is socially constructed, and peer groups valuing school resistance create significant headwinds for individual academic success. Conversely, transforming the learning context to value learning, as Freire and Flecha argue, can shift attitudes. When learning becomes valued, students often transform their attitudes, which research links to improved learning outcomes [14,15,33]. Our findings support this, demonstrating how SEAs can transform students’ attitudes towards learning. The survey showed 78.6% of participants enjoyed learning after participating in IGs or DLGs, valuing peer support (78.6% agreeing “I enjoy learning when my friends help me”), and open idea exchange (78.3% agreeing “it is good to hear other people’s ideas”). This indicates that IGs and DLGs create a context where learning is positively valued, fostering solidarity and collaboration, shifting students towards learning rather than resistance. This context transformation, as per Mead’s theory [6], leads to identity recreation based on new values. Our evidence suggests SEAs improve academic performance by positively transforming the learning context and students’ attitudes.

Analyzing IGs and DLGs reveals subtle differences in fostered attitudes. IGs emphasize collaborative work and peer support, as reflected in high ratings for items #8 and #9. DLGs, however, prioritize self-expression and self-confidence, with variance explained by items #2, #10, and #11. Item #11 directly relates to the DLG context, while items #2 and #10 suggest DLGs cultivate a positive learner self-image. Significant chi-square values in both cases support the relationship between participation and positive attitudes towards learning.

Reliability analysis for IGs highlights item #5 (“Learning in school is better when we have other adults to work with us”) as highly correlated, supporting Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) concept. The presence of a facilitator, guiding but not directing, differentiates IGs from other collaborative learning methods, emphasizing the importance of adult guidance in dialogic interaction [15].

For DLGs, item #11 (“I like discussing the books we read with the class”) shows the strongest correlation, reflecting the core activity of DLGs. Students value shared reading and discussion, aligning with the known benefits of DLGs for reading comprehension [41,52].

The high response rate to item #1 (“We learn best when the teacher tells us what to do”) is surprising, given the student-centered nature of IGs and DLGs. This might reflect ingrained classroom norms [26] and the traditional teacher role as knowledge transmitter. Even within SEAs, students may retain conventional perceptions of the teacher’s role, influencing their attitudes towards learning in subtle ways.

In conclusion, the SAM test demonstrates that students participating in IGs and/or DLGs exhibit demonstrably positive attitudes towards learning. This positive shift in attitude may be a key factor underlying the improved learning outcomes observed in other SEA studies [11–15].

Future Implications

This research validates the positive impact of SEAs on attitudes towards learning, but further research is needed to establish causality. Comparative studies contrasting SEAs with other pedagogical approaches are necessary to isolate the specific contribution of SEAs to attitudinal change.

The study highlights the crucial role of social context in shaping attitudes towards learning. The emphasis on solidarity, interaction, and sharing within IGs and DLGs appears central to fostering positive attitudes. Future research could explore the attitudinal outcomes of educational interventions with contrasting principles, such as individualistic learning approaches.

Our findings suggest that improved academic performance in SEAs is mediated by a positive shift in students’ attitudes towards learning through context transformation. While promising, further replication is crucial to confirm this relationship. Nevertheless, this research underscores the importance of teachers’ instructional design and classroom organization in fostering positive attitudes towards learning and ultimately enhancing student outcomes.

Supporting Information

S1 File. SAM questionnaire: What I think about learning in school.(PDF)

Click here for additional data file. (274.3KB, pdf)

S2 File. Dataset.(SAV)

Click here for additional data file. (66.9KB, sav)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

JDP, RGC, LH and MVC acknowledge funding from the EU Commission (grant num. 2015-1-ES01-KA201-016327, project Schools as Learning Communities in Europe: Successful Educational Actions for all, (SEAS4ALL), ERASMUS + program) and the Spanish Ramón y Cajal Grant RYC-2016-20967 for open access publication.

References

-

Harmon-Jones E, Harmon-Jones C, Amodio DM, Gable PA. Attitudes as evaluations with affective and motivational consequences. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(1):16–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00322.x.

-

Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Psychology Press; 2018.

-

Fennema E, Sherman JA. Fennema-Sherman mathematics attitudes scales: Instruments designed to measure attitudes toward the learning of mathematics by females and males. Journal for research in mathematics education. 1976;324–326.

-

Molina S, Muñoz-Silva A, Beltrán J, Pérez-Villalobos MV. Social construction of identity and academic careers: The case of Rumanian students in Spain. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2017;47(1):105–120.

-

Rosenthal R, Jacobson L. Pygmalion in the classroom. The Urban Review. 1968;3(1):16–20.

-

Mead GH. Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago press; 1934.

-

Flecha R. Successful educational actions for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2015;45(2):173–199.

-

Willis P. Learning to labour: How working class kids get working class jobs. Saxon House; 1977.

-

Bruner JS. The culture of education. Harvard university press; 1996.

-

Murayama Y, Saito A, Yeung AS, Niiyama M, Shibata K. Building confidence in learning science: A field experiment in culturally enriched science museums. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2013;50(6):733–750.

-

Aubert A, Flecha A, García C, Flecha R, Racionero S. Aprendizaje dialógico en la sociedad de la información. [Dialogic learning in the information society]. Hipatia Editorial; 2008.

-

Elboj C, Oliver E. Dialogic learning and overcoming inequalities in education. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2015;45(2):159–171.

-

García-Carrión R, Molina S, Wegner K, Claasen R. The role of families and other adults in inclusive schools: Evidence from inclusive classrooms in Germany and Spain. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2017;32(3):343–361.

-

López-Íñiguez G, Rodríguez-Sedano A, Luzon JM. Dialogic literary gatherings: Transforming reading into social action. Language and Literacy. 2019;21(1):73–89.

-

Wilkinson IA, Varelas M, Howley I, Banes RD, McAnulla F, Mitcham C. “Because science is like a puzzle”: চতুর্থ graders’ engagement in scientific argumentation in the context of interactive groups. International Journal of Educational Research. 2017;86:41–54.

-

Ballesteros-Valdés P, Guerra P, Muñoz-Silva A, Civís M, Roldán S, Planas N, et al. Impact of interactive learning environments on prosocial behaviour: An inclusive study in primary education classrooms. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182695.

-

বাড়িতে C, Ríos O, Maraver ML, Flecha R. Friendship and solidarity among Roma and non-Roma students in inclusive classrooms: Beyond cultural stereotypes. Social Inclusion. 2019;7(2).

-

Renaud L. Attitudes and dispositions towards mathematics at the beginning of university: what are we talking about? what are the relationships? Annales de didactique et de sciences cognitives. 2010;15:175–195.

-

Ma X, Kishor N. Assessing the relationship between attitude toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics: A meta-analysis. Journal for research in mathematics education. 1997;26–47.

-

Hannula MS. Attitude towards mathematics: Emotions, expectations and values. Educational studies in mathematics. 2002;49(1):25–46.

-

Neale DCS. The role of attitudes in learning mathematics. The Arithmetic Teacher. 1969;16(8):631–639.

-

Blalock CL, Lichtenstein MJ, Indrisano R, Croninger RG, Giangreco MR. Science notebooks: A tool for promoting meaningful engagement in science for all students. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2008;41(5):391–408.

-

Masgoret AM, Gardner RC. Attitudes, motivation, and integrative orientation: Assessing their relationships to oral proficiency. Language learning. 2003;53(1):167–191.

-

Ruffell M, Mason J, Allen B. Studying attitude to mathematics. Educational studies in mathematics. 1998;35(1):1–18.

-

Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press; 1978.

-

Yackel E, Cobb P. Sociomathematical norms, argumentation, and autonomy in mathematics. Journal for research in mathematics education. 1996;458–477.

-

Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press; 1991.

-

Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge university press; 1998.

-

Brousseau G. Theory of didactical situations in mathematics: Didactique des mathématiques, 1970–1990. Springer Science & Business Media; 2006.

-

Gillies RM. The effects of cooperative learning on students’ behaviours and interactions during group work. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2003;18(2):103–123.

-

Lin C, Zhang D, Zheng B, Chen G, Fischer F. Peer learning in online collaborative learning environments: The role of peer feedback. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. 2016;11(4):459–483.

-

Jussim L, Harber KD. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies, knowns and unknowns, resolves and unresolved questions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9(2):131–155.

-

Rubie-Davies CM. Teacher expectations and student outcomes: Research on self-fulfilling prophecies and related issues. Routledge; 2015.

-

European Commission. INCLUD-ED. Strategies for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe from education. European Commission; 2012.

-

Wells G. Dialogic inquiry: Towards a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge university press; 1999.

-

Mercer N, Littleton K. Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. Routledge; 2007.

-

Habermas J. The theory of communicative action, vol. 1: Reason and the rationalization of society. Beacon press; 1984.

-

Freire P, Macedo D. Literacy: Reading the word and the world. Greenwood Publishing Group; 1987.

-

Giroux HA. Literacy and the pedagogy of empowerment. Critical theory and educational practice. 1991;311–336.

-

Flecha A. Reading as dialoge. In: Social approaches to learning: Contributions of Vygotsky and Freire. Psychology Press; 2000. pp. 91–107.

-

Bakhtin MM. Problems of dostoevsky’s poetics, vol. 8. University of Minnesota Press; 1984.

-

McLeod DB. Affective domain and mathematical problem solving: A review of research.

-

Di Martino P, Zan R. ‘Me and maths’: towards a definition of attitude grounded on students’ narratives. Journal of Mathematics Education. 2011;4(1):27–48.

-

Evans P, Shaw K,্পণপয়যযy১L. Children’s attitudes to mathematics. Routledge; 2012.

-

Gómez-Chacón IM. Affective pathways in mathematics learning. Mathematics Education Research Journal. 2000;12(2):162–180.

-

Hart LA. Affect and mathematics education. Journal for research in mathematics education. 1989;38–59.

-

Freire P. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Publishing USA; 2014.

-

Murayama K, Pekrun R, Lichtenfeld S, vom Hofe R. Predicting long-term growth in students’ mathematics achievement: The unique contributions of motivation and cognitive strategies. Child development. 2013;84(4):1475–1490.

-

Singh K, Granville M, Dika S. Mathematics and science achievement: Effects of motivation, interest, and academic engagement. The journal of educational research. 2002;95(6):323–332.

-

Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British journal of psychiatry. 1985;147(6):598–611.

-

Werner EE. Protective factors and individual resilience. Handbook of early childhood intervention. 1994;97–116.

-

Mercer N. The guided construction of knowledge by young people in classroom talk.