Rigor in education is often misunderstood, interpreted differently by many. While its practical application varies, at its core, rigor signifies student engagement in challenging tasks. However, rigorous learning isn’t about overly complex activities but rather about designing learning experiences that strategically employ higher-order thinking skills. Educators can cultivate rigor by shifting focus from rote memorization to activities that require students to actively analyze, evaluate, and create.

Examples of this shift are evident in innovative high schools like the XQ schools. Purdue Polytechnic High School students demonstrated rigor by constructing cardboard boats capable of traversing a swimming pool as part of passion projects. New Harmony High School students engaged in higher-order thinking by crafting original narratives set in futures devastated by climate change. Latitude High School students applied complex skills by building tiny houses for unhoused youth. These diverse projects exemplify authentic learning experiences infused with rigorous elements, all designed to encourage students to apply higher-order thinking skills to their learning process.

Higher-order thinking (HOT) skills are pivotal in moving students beyond mere memorization and recall. Instead, HOT skills empower them to become active learners, capable of analyzing information, evaluating evidence, and creating innovative solutions to demonstrate a deep understanding of the material.

High school provides a particularly fertile ground for nurturing higher-order thinking skills, coinciding with significant developmental milestones in adolescence. As students mature, their capacity for abstract thought expands, their ability to formulate unique ideas strengthens, and they become more adept at analyzing diverse perspectives, even those differing from their own. This developmental trajectory is the foundation of the XQ Learner Outcomes, which are structured to activate higher-order thinking by encouraging students to become original thinkers prepared for an uncertain future, possessors of fundamental knowledge, and self-directed lifelong learners.

Recognizing that students enter classrooms with varied levels of prior knowledge, designing lessons that effectively target, differentiate, and scaffold HOT skills demands considerable planning and foresight. Project-based learning (PBL) and inquiry-based learning (IBL) models offer ideal frameworks for teachers to seamlessly integrate and cultivate these essential skills. By clearly defining and understanding the characteristics of higher-order thinking skills, educators can more effectively structure their curriculum to explicitly teach these competencies, thereby empowering students to evolve into the thinkers and creators of the next generation.

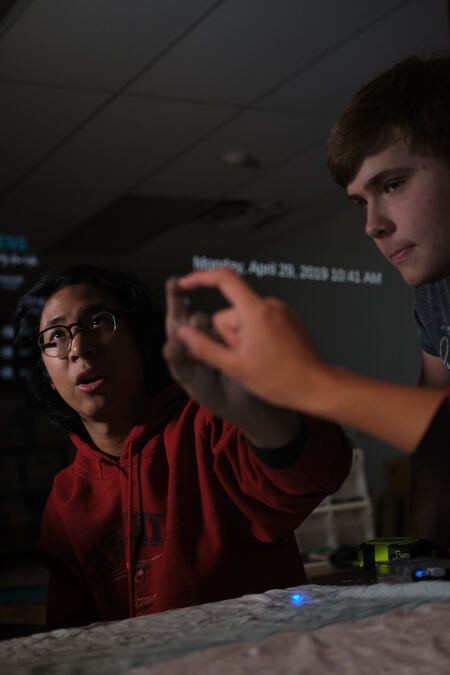

Students at PSI High School engage in collaborative problem-solving, demonstrating higher-order thinking skills through teamwork and technology.

Defining Higher-Order Thinking Skills: Moving Beyond Memorization

Higher-order thinking skills represent a progression of cognitive abilities that propel students beyond simple rote memorization and recall, encouraging them to engage in more complex and comprehensive levels of thought. This involves transitioning from passively receiving information to actively applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. HOT skills challenge students to utilize memorized facts and information in dynamic and novel ways. This could include making inferences, connecting seemingly disparate ideas to form larger, integrated concepts, or developing entirely original creations.

A widely recognized framework for understanding this progression from lower to higher-order thinking is Bloom’s Taxonomy. Initially developed in 1956 by a group of educators led by Benjamin Bloom and subsequently revised in 2001, Bloom’s Taxonomy outlines six levels of cognitive complexity:

- Remember: Recalling basic facts and information.

- Understand: Grasping the meaning and implications of concepts.

- Apply: Using knowledge in new and concrete situations.

- Analyze: Breaking down information into component parts and understanding their relationships.

- Evaluate: Judging the value of information or ideas based on criteria.

- Create: Producing new or original work.

Another valuable framework for conceptualizing HOT skills is Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK), developed by Norman Webb. DOK comprises four levels that describe the cognitive demand required to engage with content:

- Recall and Reproduction: Basic recall of facts or procedures.

- Skills and Concepts: Applying skills and concepts in familiar contexts.

- Strategic Thinking: Reasoning, planning, and using evidence to solve problems.

- Extended Thinking: Complex reasoning, in-depth analysis, and creative problem-solving over time.

Both Bloom’s Taxonomy and Webb’s Depth of Knowledge serve as excellent starting points for educators when designing learning activities that are both complex and actively engaging. These frameworks enable teachers to strategically plan lessons by first identifying the specific higher-order thinking skills they aim to cultivate in their students. Utilizing the principles of backward design, educators can begin lesson planning by posing crucial questions such as: “What foundational knowledge do students need at the outset of a project to ultimately achieve the higher-order goal, such as creating an original product or solution?”

But what do these higher-order categories—creating, evaluating, and extended thinking—actually look like when implemented in a classroom setting? Let’s delve into specific types of higher-order thinking and explore practical examples of their application.

Cultivating Critical Thinking in the Classroom

Critical thinking is another term in education that, while frequently used, often lacks a singular, universally accepted definition. At its most fundamental level, critical thinking is the ability to question assumptions, interpret information, and form reasoned judgments about ideas, rather than passively accepting them at face value. Essentially, critical thinking is an active, student-driven process.

One effective example of fostering critical thinking in the classroom involves having students critically analyze news headlines. Educator and instructional coach Dara Savage advocates for the FIRE method to guide students in this process. The FIRE method prompts students to:

- Focus: Initially react and respond to the news headline.

- Identify: Pinpoint a specific phrase or element within the headline or accompanying photo and analyze it in writing.

- Reframe: Re-evaluate their initial response by focusing on a particular word, phrase, or section they previously identified.

- Exchange: Share their refined thoughts with a classmate, connecting the discussion to broader themes being studied in class.

The crucial element in Savage’s method that significantly accelerates the development of students’ HOT skills is the “exchange” phase. Providing students with a structured avenue to share their evolving understandings is essential. This peer interaction allows them to analyze, synthesize, and critically evaluate the feedback they receive, further refining their thinking.

In essence, critical thinking encourages students to transcend mere memorization and understanding of new information, pushing them to actively analyze and evaluate what they are learning. This process necessitates making active connections between various concepts and ideas. For example, students might compare a new piece of information to their existing knowledge base or to their personal experiences to assess its validity and relevance.

Enhancing Comprehension: Active Meaning-Making

Comprehension is frequently discussed in the context of reading and literacy, but its relevance extends far beyond these areas. Similar to critical thinking, comprehension involves grasping both the explicit and implicit meanings of a subject. For instance, a student demonstrating comprehension of algebra isn’t just memorizing formulas; they understand how to apply and utilize those formulas to make predictions and evaluate more complex concepts. Comprehension, therefore, represents a significant step beyond rote memorization, requiring students to actively apply their knowledge to build an evolving and nuanced understanding.

Unlike passive memorization, comprehension is an inherently active process. To truly comprehend a new concept, students must first extract meaning from it and then connect it to their existing knowledge framework. This active integration of new information allows students to understand how it fits into their broader understanding of the world and their own experiences.

One insightful framework for thinking about fostering comprehension is Marzano’s Nine Instructional Strategies, a research-backed sequence of instructional methods designed to ensure rigorous learning. In Marzano’s framework, building comprehension is achieved by actively engaging students with new knowledge and providing them with opportunities to practice and deepen their understanding. Effective strategies at these levels include:

- Chunking content: Breaking down complex information into smaller, more digestible segments.

- Examining reasoning: Guiding students to analyze their own thought processes and justifications.

- Practicing skills: Providing ample opportunities to practice newly acquired skills, strategies, and processes.

Fostering Metacognition: Thinking About Thinking

Metacognition, often described as “thinking about thinking,” is a crucial higher-order skill that empowers students to become more aware of and regulate their own learning processes. As explained by Reading Rockets, metacognition encourages students to become active participants in their education by prompting them to consider questions such as: “How well have I truly mastered this concept?” “What additional knowledge do I need to effectively analyze this information?” “What are my strengths as a learner, and in what areas do I require more support?”

By engaging in metacognitive reflection, students develop a deeper understanding of their learning strengths and weaknesses, enabling them to take ownership of their learning journey and become more effective self-directed learners.

Cultivating Evaluation Skills: Judgment with Justification

The Learning Center at UNC defines evaluation as “making judgments about something based on established criteria and standards.” It’s important to note that evaluation in an educational context doesn’t always lead to a single, definitive “correct” answer. Instead, the emphasis is on students making reasoned judgments and, crucially, supporting those judgments with logical reasoning and evidence.

To stimulate evaluation skills, teachers can pose questions that prompt students to form and justify opinions, such as:

- “Do you personally like or dislike, agree or disagree with a particular author’s perspective or decision?”

- “In a given situation, what course of action would you choose and why?”

- “When presented with multiple approaches to a challenge, which approach do you believe is the most effective, and what evidence supports your choice?”

To encourage in-depth evaluation, moving beyond superficial answers, teachers should consistently follow up with probing questions that push students to delve deeper. This might involve asking students how they can substantiate their responses by synthesizing evidence from various sources, critically evaluating the reliability of those sources, and drawing relevant connections to examples from their own lives and experiences.

Synthesis and Analysis: Connecting and Deconstructing Information

Synthesis and analysis are two complementary higher-order thinking skills that work in tandem to enhance understanding by exploring the relationships between different pieces of knowledge or information. The Learning Center at UNC defines synthesis as: “considering individual elements in conjunction with each other to draw broader conclusions, identify overarching themes, or determine common elements.” Synthesis involves shifting from a focus on individual components to understanding the integrated whole. Conversely, analysis requires students to do the opposite: to break down larger concepts or systems into their smaller, constituent parts to understand their individual roles and interactions.

Common activities designed to promote synthesis often include tasks that require students to:

- Generalize information to construct new, broader understandings.

- Explore the intricate relationships and connections between seemingly disparate concepts.

- Identify recurring patterns and categorize information based on shared characteristics.

Analysis activities, on the other hand, typically involve questions that prompt students to:

- Understand how individual parts contribute to the functioning of the larger whole.

- Deconstruct complex concepts or problems to understand various underlying perspectives.

- Examine and evaluate the individual components of a concept or problem in detail.

Developing Inference Skills: Drawing Conclusions from Evidence

An inference is defined as “a conclusion or opinion that is formed because of known facts or evidence.” The very nature of inference inherently involves higher-order thinking because it requires students to take existing facts or evidence that they have comprehended and use them to create new knowledge or understanding.

Students sometimes misinterpret making inferences as simply guessing or prematurely jumping to conclusions. To mitigate this, it’s beneficial to break down the step-by-step mental processes involved in making a valid inference. By slowing down their thinking and making the process explicit, you can guide students to arrive at understandings that are firmly grounded in evidence and critical thinking. For example, when making an inference, students should:

- Begin by carefully identifying relevant facts and evidence directly related to the situation.

- Critically consider any personal assumptions or biases they might hold that could potentially influence their interpretation of the facts and evidence.

- Systematically test their initial inference to determine if it is well-supported by the evidence or if it needs to be revised or reconsidered based on further analysis.

Students at Washington Leadership Academy leverage virtual reality technology to engage in immersive learning and develop higher-order thinking skills in a collaborative environment.

Creating Conditions for Higher-Order Thinking in the Classroom

To effectively teach higher-order thinking skills, educators should adopt a “backward design” approach, beginning with the desired learning outcomes in mind. This process starts by asking fundamental questions such as, “What specific types of thinking will students need to employ to successfully achieve the learning goals?” By clarifying these end goals, teachers can more effectively scaffold students’ development of foundational, lower-order thinking skills, ensuring they build a robust base of conceptual understanding that supports deeper, more complex thought processes.

This backward design cycle is most effective when integrated with overlapping teaching methodologies such as project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, and experiential learning. For instance, at PSI High, an XQ school located in Sanford, Florida, students undertook a project to design micromuseums focused on exploring different facets of their local history. Through this project, they applied higher-order thinking skills to analyze the specific needs of their community and to create original and innovative ways of presenting and interpreting local histories.

Experiential learning takes a similar approach, emphasizing learning by doing, often in settings that extend beyond the traditional classroom. Successful and multi-layered PBL activities frequently incorporate experiential learning components that actively engage students’ HOT skills. In inquiry-based learning, students adopt the role of scientists, actively constructing knowledge through investigation and exploration rather than passively receiving it.

Each of these pedagogical methods necessitates students using higher-order thinking to effectively apply their skills and knowledge in unique, open-ended, and often unpredictable situations. Success in implementing these methods hinges on carefully designing learning experiences around clearly defined key objectives and consistently providing opportunities for students to assess their progress and reflect on their mastery of the material. Below is a step-by-step guide to this process:

1. Identify Diverse Learning Styles: Creating Inclusive Conditions

Effective scaffolding begins with teachers gaining a deep understanding of how their students learn best. While higher-order thinking strategies can be adapted to accommodate a wide range of learning styles, it is crucial to identify the necessary stepping stones and accommodations to ensure equitable learning opportunities for all students. When planning learning objectives, it’s essential to consider the neurodiversity present in your classroom. Ask yourself: “How can I incorporate opportunities that cater to visual, verbal, concrete, and abstract thinking?” “How much time will my students realistically need to complete complex thinking tasks effectively?” “What mechanisms will I use to consistently check for student understanding throughout the learning process?”

Educator Karen Harris recommends using thinking inventories—structured sets of essential questions—as a strategy to ensure all learners are included in higher-order thinking activities. By introducing thinking inventories at the beginning of a unit, students are given the opportunity to contemplate these questions at their own pace throughout their learning. They can then approach these essential questions through a variety of activities before returning to them for deeper reflection at the conclusion of the project.

2. Define Clear Learning Objectives: Setting Purposeful Conditions

Begin each project or lesson by explicitly defining the specific higher-order thinking skills students are expected to master within the project’s context. Utilize frameworks like Bloom’s Taxonomy and Webb’s Depth of Knowledge to clearly articulate the desired level and type of higher-order thinking—such as analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, or creating.

Clearly defined objectives are essential to ensure that the activities and lessons chosen are directly aligned with the specific thinking skills you aim to promote. Common pitfalls in lessons designed to foster higher-order thinking include activities that may appear rigorous on the surface but fail to genuinely engage the intended thinking skills. For instance, students might be asked to “create” a diorama representing a scene from a book they have read. While this activity involves creation, it may not necessarily require them to generate new knowledge or deeper understanding. In contrast, a more effective higher-order thinking task designed to achieve the objective of “create” might involve asking students to write an original story imagining a character from the book placed in a completely new and unexpected situation. To ensure students are truly operating at a higher cognitive level, it is crucial to incorporate time for activities at lower cognitive levels that reinforce their basic comprehension and activate relevant prior knowledge.

3. Select Relevant Activities & Lessons: Creating Authentic Conditions

Meaningful and engaged learning, a core XQ Design Principle for innovative schools, is most effectively achieved when students have access to authentic learning experiences that resonate with their lives and interests. When planning activities and lessons, prioritize creating these authentic experiences by selecting activities that directly connect to students’ lived experiences. Consider how you can structure lessons around real-world challenges and issues that students can readily recognize and relate to. When students perceive the direct relevance of their learning to their own lives, they are far more likely to be intrinsically motivated to ask more profound questions, leading to deeper engagement and higher-order thinking.

Explore these strategies to emphasize relevance and rigor in higher-order thinking lessons:

- Choose compelling topics that are directly relevant to students’ lives, allowing them to explore diverse perspectives and viewpoints.

- Establish local connections, including forming strategic partnerships with local non-profit organizations and businesses.

- Design authentic projects that challenge students to tackle complex, real-world problems, particularly those that are directly relevant to their local communities.

4. Implement Effective Assessment and Reflection: Conditions for Growth

Traditional assessment methods often primarily focus on evaluating students’ memorization of facts and information. While standardized tests may include multiple-choice questions framed around “analyze this” or “evaluate that,” these question types are often more effective at gauging basic comprehension rather than a student’s true ability to apply higher-order thinking skills in practice.

Assessments of higher-order thinking should instead focus on evaluating the depth of students’ thinking processes and their ability to apply reasoned judgment. If teachers aim to assess a student’s progress against the learning objectives established at the outset of a lesson or project, constructed response tasks or reflective journals on project experiences can provide a far more comprehensive and nuanced picture of a student’s HOT skill development. Summative assessments are best utilized for broadly monitoring student progress over time and should primarily inform instructional adjustments to better meet student needs.

Higher-Order Thinking: Key to XQ Learner Outcomes

Higher-order thinking significantly enhances academic achievement by guiding students beyond rote memorization and fostering the development of essential creative and critical thinking skills. Rather than simply training students to memorize content solely for the purpose of passing tests, cultivating higher-order thinking prepares students to become original thinkers and learners for life—individuals who are self-directed, inherently curious, and adept at seeking out and effectively applying information to solve complex problems. This holistic development of higher-order thinking skills is at the very heart of the XQ Learner Outcomes.

By incorporating these strategies for fostering higher-order thinking into your classroom, you can significantly deepen student engagement and effectively prepare students to creatively and confidently address the challenges of the future.

Photo at top by Chris Chandler

More from XQ

See all

[

Podcast: Tennessee High Schoolers Solved a Nearly 40-Year-Old Serial Murder Mystery

By Edward Montalvo

](https://xqsuperschool.org/teaching-learning/tennessee-high-schoolers-solved-a-nearly-40-year-old-serial-murder-mystery/) [

Watch: New Film Inspires America to Rethink High School

By Team XQ

](https://xqsuperschool.org/education-policy/watch-new-film-inspires-america-to-rethink-high-school/) [

Watch: Rethinking High School in the DC Public Schools

By Team XQ

](https://xqsuperschool.org/teaching-learning/watch-rethinking-high-school-in-the-dc-public-schools/)

See all