The Factor Theorem is a powerful tool in algebra that simplifies polynomial factorization and root-finding. But when do you actually learn factor theorem in your mathematical journey? Typically, the factor theorem is introduced in high school algebra, often around 9th or 10th grade, as part of a broader unit on polynomials and algebraic manipulation. It builds upon foundational concepts like polynomial division and the remainder theorem, acting as a shortcut for determining factors of polynomials and uncovering their roots.

This article will delve into the factor theorem, explaining what it is, how it works, and why it’s an essential concept to grasp in your algebra education. We’ll explore the theorem itself, its proof, practical applications, and differentiate it from its close relative, the remainder theorem.

What Exactly is the Factor Theorem?

The Factor Theorem is closely linked to the remainder theorem and serves as a specific case within polynomial theory. In essence, it establishes a direct connection between the factors of a polynomial and its zeros (or roots). Think of it as a detective tool that helps you identify factors of polynomials efficiently.

The theorem essentially allows you to determine if a linear expression (like x – a) is a factor of a polynomial f(x) without performing long division. This significantly simplifies the process of factoring polynomials, especially those of higher degrees.

Factor Theorem Statement: The Core Principle

Here’s the formal statement of the factor theorem:

For a polynomial f(x) of degree n ≥ 1, and any real number ‘a’, then (x – a) is a factor of f(x) if and only if f(a) = 0.

Let’s break down what this means:

- “f(x) is a polynomial of degree n ≥ 1”: This simply means we are dealing with polynomials (expressions with variables raised to non-negative integer powers) of degree one or higher (linear, quadratic, cubic, etc.).

- “‘(x – a) is a factor of f(x)'”: This means that if you divide the polynomial f(x) by (x – a), the remainder will be zero. In other words, (x – a) divides evenly into f(x).

- “if and only if f(a) = 0”: This is the crucial part. It states a bidirectional relationship:

- If (x – a) is a factor of f(x), then f(a) must equal 0. This is the direction we often use to check if something is a factor.

- If f(a) = 0, then (x – a) is a factor of f(x). This is the direction we often use to find factors.

To fully understand the factor theorem, it’s important to grasp the concept of a “zero of a polynomial.”

Understanding Zeros of a Polynomial

Before you dive deeper into the factor theorem, understanding polynomial zeros is key. A zero (or root) of a polynomial g(y) is a value ‘a’ for y such that when you substitute ‘a’ into the polynomial, the result is zero, i.e., g(a) = 0. Essentially, it’s the solution to the equation g(y) = 0.

Let’s look at an example. Consider the quadratic polynomial g(y) = y² + 2y – 15. To find its zeros, we set g(y) = 0 and solve:

y² + 2y – 15 = 0

We can factor this quadratic equation:

(y + 5)(y – 3) = 0

This gives us two solutions: y = -5 and y = 3. Therefore, -5 and 3 are the zeros (or roots) of the polynomial y² + 2y – 15.

Factor Theorem Formula

The factor theorem can be expressed concisely as a formula:

g(y) = (y – a) q(y) if and only if g(a) = 0

Where:

- g(y) is the polynomial.

- (y – a) is the potential factor.

- q(y) is the quotient polynomial if (y – a) is indeed a factor.

- ‘a’ is a real number and a zero of the polynomial if g(a) = 0.

This formula highlights that if (y – a) is a factor, then the polynomial g(y) can be perfectly expressed as the product of (y – a) and another polynomial q(y), with no remainder.

Here’s a summary of equivalent statements based on the factor theorem for any polynomial g(y):

- (y – a) is a factor of g(y).

- g(a) = 0.

- When g(y) is divided by (y – a), the remainder is zero.

- ‘a’ is a solution to g(y) = 0 and a zero of the function g(y).

Proof of the Factor Theorem

To solidify your understanding, let’s look at the proof of the factor theorem. It elegantly uses the polynomial division algorithm and the remainder theorem.

Consider a polynomial g(y) being divided by (y – a). According to the division algorithm, we can write:

Dividend = (Divisor × Quotient) + Remainder

Applying this to our polynomials:

g(y) = (y – a) q(y) + R

Where:

- g(y) is the dividend polynomial.

- (y – a) is the divisor (a linear binomial).

- q(y) is the quotient polynomial.

- R is the remainder.

From the Remainder Theorem, we know that the remainder R when g(y) is divided by (y – a) is simply g(a). Therefore, we can rewrite the equation as:

g(y) = (y – a) q(y) + g(a)

Now, let’s consider the condition stated by the factor theorem: if g(a) = 0, then (y – a) is a factor.

If we substitute g(a) = 0 into the equation above, we get:

g(y) = (y – a) q(y) + 0

g(y) = (y – a) q(y)

This equation clearly shows that g(y) is expressed as a product of (y – a) and q(y), meaning (y – a) is indeed a factor of g(y).

Conversely, if (y – a) is a factor of g(y), it means the division of g(y) by (y – a) results in a zero remainder. From the remainder theorem, we know the remainder is g(a), so if the remainder is zero, then g(a) must be zero.

Thus, we have proven both directions of the “if and only if” statement, confirming the factor theorem’s validity. The factor theorem is indeed a direct consequence of the remainder theorem.

How to Use the Factor Theorem in Practice

Let’s illustrate how to use the factor theorem with a practical example.

Example: Determine if (y + 5) is a factor of the polynomial 2y² + 7y – 15.

Solution:

- Set the potential factor to zero: y + 5 = 0 => y = -5

- Substitute this value into the polynomial: g(y) = 2y² + 7y – 15

g(-5) = 2(-5)² + 7(-5) – 15 - Evaluate: g(-5) = 2(25) – 35 – 15 = 50 – 35 – 15 = 0

- Interpret the result: Since g(-5) = 0, according to the factor theorem, (y + 5) is indeed a factor of 2y² + 7y – 15.

Factoring Higher-Degree Polynomials Using the Factor Theorem

The real power of the factor theorem shines when factoring polynomials of degree three or higher. Here’s a step-by-step procedure:

- Step 1: Test Potential Factors: Use the Rational Root Theorem (or educated guessing based on the constant term’s factors) to identify possible rational roots ‘a’. For each potential root ‘a’, calculate f(a).

- Step 2: Identify a Factor: If f(a) = 0, then (x – a) is a factor of f(x) according to the Factor Theorem.

- Step 3: Polynomial Division: Divide the original polynomial f(x) by the factor (x – a) using polynomial long division or synthetic division. This will give you a quotient polynomial of a lower degree.

- Step 4: Factor the Quotient: If the quotient is a quadratic, factor it using standard quadratic factorization techniques. If it’s still of a higher degree, repeat steps 1-3 on the quotient polynomial.

- Step 5: Complete Factorization: Express the original polynomial as a product of all the factors you have found.

Let’s work through an example to factor a cubic polynomial:

Example: Show that (y + 2) is a factor of y³ – 6y² – y + 30 and then fully factorize the polynomial and find its zeros.

Solution:

-

Test (y + 2) as a factor: Set y + 2 = 0 => y = -2.

Substitute y = -2 into g(y) = y³ – 6y² – y + 30:

g(-2) = (-2)³ – 6(-2)² – (-2) + 30 = -8 – 24 + 2 + 30 = 0.

Therefore, (y + 2) is a factor. -

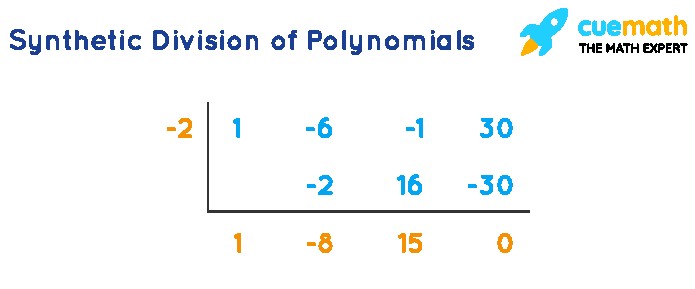

Divide using synthetic division:

-2 | 1 -6 -1 30 | -2 16 -30 ----------------- 1 -8 15 0The remainder is 0, confirming (y + 2) is a factor. The quotient is y² – 8y + 15.

-

Factor the quadratic quotient: Factor y² – 8y + 15. We look for two numbers that multiply to 15 and add to -8. These are -3 and -5. So, y² – 8y + 15 = (y – 3)(y – 5).

-

Complete Factorization: Combining the factor (y + 2) and the factored quadratic quotient, we get:

y³ – 6y² – y + 30 = (y + 2)(y² – 8y + 15) = (y + 2)(y – 3)(y – 5). -

Zeros: The zeros of the polynomial are found by setting each factor to zero:

y + 2 = 0 => y = -2

y – 3 = 0 => y = 3

y – 5 = 0 => y = 5Thus, the zeros are -2, 3, and 5.

Factor Theorem vs. Remainder Theorem: Key Differences

While closely related, the factor theorem and remainder theorem address slightly different aspects of polynomial division.

- Remainder Theorem: Focuses on finding the remainder when a polynomial is divided by a linear binomial (x – a). It states that the remainder is simply f(a).

- Factor Theorem: Focuses on determining if a linear binomial (x – a) is a factor of a polynomial. It states that (x – a) is a factor if and only if f(a) = 0 (meaning the remainder is zero).

Consider the polynomial g(y) = y² – 2y + 1 to illustrate the difference.

Using the Remainder Theorem: Let’s find the remainder when g(y) is divided by (y – 3). According to the remainder theorem, the remainder is g(3).

g(3) = (3)² – 2(3) + 1 = 9 – 6 + 1 = 4

So, the remainder is 4.

Using the Factor Theorem: Let’s check if (y – 1) is a factor of g(y). We evaluate g(1).

g(1) = (1)² – 2(1) + 1 = 1 – 2 + 1 = 0

Since g(1) = 0, the factor theorem tells us that (y – 1) is a factor of y² – 2y + 1. Indeed, y² – 2y + 1 = (y – 1)².

Key Takeaway: The remainder theorem gives you the remainder, while the factor theorem tells you if the remainder is zero, which is the condition for being a factor.

Important Notes on the Factor Theorem:

- The factor theorem is a cornerstone for factoring polynomials and finding their roots.

- Factoring polynomials has practical applications in various real-world scenarios, such as resource allocation, financial modeling, and engineering calculations.

- Remember the core condition: (y – a) is a factor of polynomial g(y) if and only if g(a) = 0.

Related Concepts:

- Remainder Theorem

- Polynomials

- Synthetic Division of Polynomials

- Factorization of Quadratic Equations

Factor Theorem Examples

Let’s solidify your understanding with more examples.

Example 1: Use the factor theorem to determine if (y + 1) is a factor of the polynomial 3y⁴ + y³ – y² + 3y + 2.

Solution:

- Set y + 1 = 0 => y = -1.

- Substitute y = -1 into the polynomial: 3y⁴ + y³ – y² + 3y + 2.

3(-1)⁴ + (-1)³ – (-1)² + 3(-1) + 2 = 3(1) + (-1) – 1 – 3 + 2 = 3 – 1 – 1 – 3 + 2 = 0. - Since the result is 0, (y + 1) is a factor of 3y⁴ + y³ – y² + 3y + 2.

Example 2: Check if (2y + 1) is a factor of the polynomial 4y³ + 4y² – y – 1 using the factor theorem.

Solution:

- Set 2y + 1 = 0 => y = -1/2.

- Substitute y = -1/2 into the polynomial: 4y³ + 4y² – y – 1.

4(-1/2)³ + 4(-1/2)² – (-1/2) – 1 = 4(-1/8) + 4(1/4) + 1/2 – 1 = -1/2 + 1 + 1/2 – 1 = 0. - Since the remainder is 0, (2y + 1) is a factor of 4y³ + 4y² – y – 1.

Visual learning can significantly enhance understanding and retention of mathematical concepts, moving beyond rote memorization.

Book a Free Trial Class

Practice Questions on Factor Theorem

Test your understanding with these practice questions:

- Determine if (x – 2) is a factor of x³ – 4x² + 5x – 2.

- Is (x + 3) a factor of 2x⁴ + 5x³ – 7x² – 8x + 12?

FAQs on Factor Theorem

What is the Factor Theorem?

The factor theorem states that for a polynomial f(x) and a number ‘a’, (x – a) is a factor of f(x) if and only if f(a) = 0. It’s a valuable tool for factoring polynomials and finding their roots, particularly in high school algebra.

How do you Use the Factor Theorem?

To use the factor theorem:

- To check if (x – a) is a factor of f(x), calculate f(a). If f(a) = 0, then (x – a) is a factor.

- To factor a polynomial, test potential factors (x – a) by checking if f(a) = 0. If it is, divide f(x) by (x – a) and repeat the process on the quotient.

What is the Factor Theorem Formula?

The core “formula” is the statement itself: (y – a) is a factor of the polynomial g(y) if and only if g(a) = 0. This leads to the expression g(y) = (y – a) q(y) when (y-a) is a factor.

Explain Factor Theorem With an Example.

Let’s check if (y + 2) is a factor of g(y) = y³ + 3y² + 5y + 6.

g(-2) = (-2)³ + 3(-2)² + 5(-2) + 6 = -8 + 12 – 10 + 6 = 0.

Since g(-2) = 0, (y + 2) is a factor of y³ + 3y² + 5y + 6.

What is the Importance of the Factor Theorem?

The factor theorem simplifies polynomial factorization, especially for higher-degree polynomials. It connects factors to roots, making it easier to find roots and understand polynomial behavior. This is crucial in algebra and pre-calculus courses you’ll encounter in high school.

What is the Difference Between Factor Theorem and Remainder Theorem?

The remainder theorem finds the remainder of polynomial division, while the factor theorem determines if the remainder is zero (indicating a factor). They are related, but serve different purposes.

Where do we Use the Factor Theorem in Real Life?

While not directly used in everyday transactions, the principles of polynomial factorization, enabled by the factor theorem, are applied in various fields like engineering, computer science (algorithm design), and economics (modeling relationships between variables).

What is the Importance of the Remainder Theorem and Factor Theorem?

Both theorems provide efficient methods for analyzing polynomials without lengthy division. They are fundamental tools in polynomial algebra.

Is Factor Theorem and Remainder Theorem the Same?

No, they are not the same but are closely related. The factor theorem is a special case of the remainder theorem where the remainder is zero.

Practice Question Answers:

Q1: What is the value of k for which (x−k) is a factor of p(x) = x⁵ − k²x³ + 2x + k − 3?

Q2: Which of the following is a factor of the polynomial p(x) = x³ + 5x² − 4x − 20?

Q3: If p(z) = 2z⁴ + 3z³ + 2pz² + 3z + 6 is perfectly divisible by (z + 2), then what is the value of p?

Q4: Which of the following is a factor of 6x³ + 5x² – 2x – 1?

Q5: For a polynomial p(x) = xⁿ − 1, where n is some natural number, p(x) is divisible by (x + 1) for ____ of n.