In the realm of psychology, understanding how learning occurs has been a central focus. Early behaviorists like B.F. Skinner and John B. Watson championed the idea that learning is solely driven by observable behaviors and external stimuli, minimizing the role of internal cognitive processes. Skinner, known for his radical behaviorism, even considered the mind a “black box,” suggesting its unknowable nature rendered it irrelevant to the study of learning. However, not all behaviorists subscribed to this strictly limited view. Edward C. Tolman, a contemporary behaviorist, challenged this perspective with groundbreaking experiments that revealed a more nuanced understanding of learning – one that acknowledged the significance of cognitive factors. Tolman’s research introduced the concept of latent learning, demonstrating that learning can indeed happen even without immediate, obvious reinforcement, thereby opening the door to cognitive psychology’s influence on learning theories.

What is Latent Learning? Exploring the Unseen

Latent learning is defined as learning that occurs without immediate behavioral expression or obvious reinforcement. Think of it as knowledge acquired “under the surface,” remaining dormant until a specific need or motivation arises to reveal it. This form of learning challenges the traditional behaviorist view that learning is solely a direct consequence of conditioning through immediate rewards or punishments. Latent learning suggests that organisms can absorb information from their environment and create internal representations of that information, even when there’s no apparent reason to do so. This learning is not immediately observable; it’s “latent” because it’s hidden, waiting for the right circumstances to be demonstrated. It becomes apparent only when the learner is motivated to utilize the previously acquired, but unspoken, knowledge. This concept was pivotal in moving the field of learning beyond the rigid constraints of strictly observable behaviors, paving the way for the integration of cognitive processes into our understanding of how we learn.

Tolman’s Rat Maze Experiment: A Classic Demonstration

Edward C. Tolman’s famous experiments with rats in mazes are a cornerstone in understanding latent learning. In a departure from traditional reinforcement-based learning studies, Tolman designed an experiment to explore learning in the absence of immediate rewards. He placed hungry rats in a maze, but unlike typical maze experiments, there was no food or reward at the end for navigating through it. He also had a control group that received food upon reaching the maze’s end.

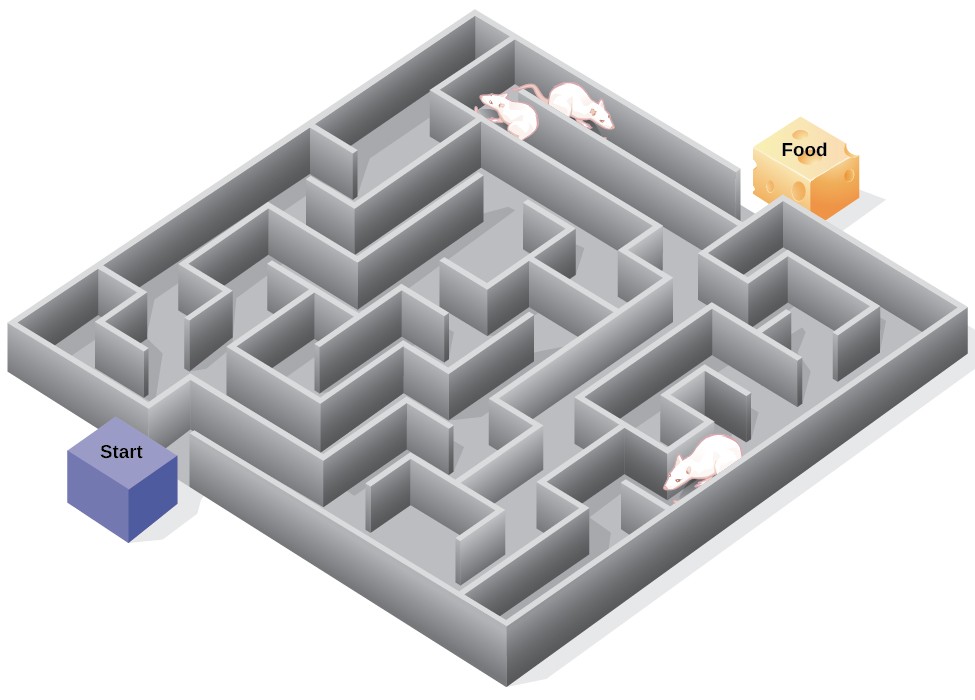

As the unreinforced rats explored the maze, something remarkable happened. They were developing what Tolman termed a cognitive map – a mental representation or internal spatial map of the maze layout (Figure 1). This mental map wasn’t immediately apparent in their behavior, as they were simply exploring without any apparent goal. However, after several sessions of unrewarded maze exploration, Tolman introduced a crucial change: he placed food in a goal box at the end of the maze.

An illustration shows three rats in a maze, with a starting point and food at the end.

An illustration shows three rats in a maze, with a starting point and food at the end.

Figure 1. Edward Tolman’s rat maze experiment demonstrated latent learning and the formation of cognitive maps in rats. Similar to navigating a video game level, the rats developed a mental understanding of the maze layout. (credit: modification of work by “FutUndBeidl”/Flickr)

The results were striking. Once the rats became aware of the food reward, the unreinforced group navigated to the goal box with remarkable speed and efficiency, almost as quickly as the comparison group that had been rewarded from the beginning. This demonstrated that the rats in the unreinforced group had been learning all along, even without any immediate reward. They had latently learned the maze layout by creating a cognitive map during their exploration, and this learning only became evident when they had a motivation (food) to express it.

Cognitive Maps: Our Internal Navigation System

The concept of the cognitive map, revealed through Tolman’s work, is crucial to grasping latent learning. A cognitive map is essentially a mental picture or spatial representation of an environment. It’s how we internally visualize and understand layouts, whether it’s a maze, a building, or even our neighborhood. These maps aren’t just visual; they encompass spatial relationships, landmarks, and routes.

Psychologist Laura Carlson’s research (2010) further highlights the importance of cognitive maps in human navigation. She suggests that the details we encode in our cognitive maps significantly impact our ability to navigate complex environments. Paying attention to specific features like unique objects or architectural details when entering a new place enhances our cognitive map and provides crucial reference points for later navigation. This explains why we might remember “the fountain near the entrance” or “the painting by the elevators” when trying to find our way in a large building – these details become key elements in our mental map.

Latent Learning in Our Daily Lives

Latent learning isn’t confined to laboratory rats; it’s a phenomenon that occurs in human learning as well. Think about children observing their parents performing tasks – they are constantly absorbing information and creating cognitive maps of how things are done, even if they don’t immediately demonstrate these skills. Later, when the need arises, this latent knowledge surfaces.

Consider the example of Ravi and his dad’s route to school. Ravi, as a passenger, learns the route passively each day. He’s building a cognitive map of the streets, turns, and landmarks, even though he isn’t actively driving or needing to navigate. When his dad is unavailable one morning, and Ravi needs to bike to school himself, his latent learning becomes apparent. He can successfully navigate the route, demonstrating that he had learned the way all along, even without actively practicing or being explicitly taught to drive the route himself.

Latent learning is a testament to the cognitive flexibility of learning. It reveals that we are constantly learning from our surroundings, often without immediate reinforcement or conscious effort. This “hidden” learning plays a vital role in our ability to adapt to new situations, solve problems, and navigate the world around us efficiently. It underscores that learning is not always a direct, immediately observable process but often a more complex cognitive undertaking that builds a reservoir of knowledge ready to be utilized when the time is right.