1. Introduction

Medical education is constantly evolving to better prepare students for the complexities of clinical practice. Traditional methods are increasingly being supplemented with approaches that actively engage students in their learning process. Among these, simulation, clerkships, and case discussions stand out as vital tools for bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Integrating these diverse educational formats, particularly through frameworks like Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, can significantly enhance learning outcomes for medical students, strengthening their clinical reasoning and practical skills. This article delves into the evidence supporting the application of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, especially within medical education, drawing upon a specific study that highlights its effectiveness in preparing future general practitioners.

2. Understanding Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

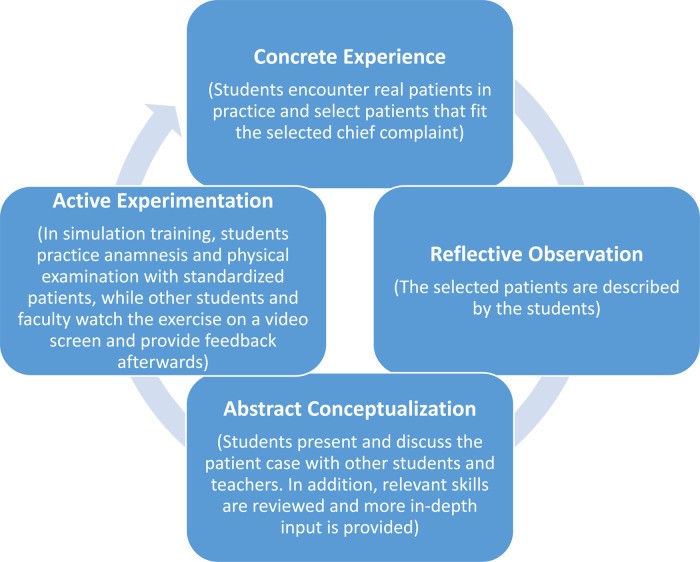

David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle is a cornerstone of adult learning theory, emphasizing learning as a process driven by experience. This cyclical model posits that effective learning occurs when a learner progresses through four distinct stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation.

-

Concrete Experience (CE): This is the initial stage where the learner encounters a new experience or situation. In medical education, this could involve direct clinical exposure during clerkships, encountering a patient with a specific ailment, or participating in a simulation exercise. This phase is about immersion and firsthand involvement.

-

Reflective Observation (RO): Following the concrete experience, learners engage in reflective observation. This involves stepping back from the experience and thoughtfully observing and reflecting upon it from different perspectives. For medical students, this could be reviewing patient cases, discussing experiences with peers or mentors, or journaling about their observations and feelings during clinical encounters.

-

Abstract Conceptualization (AC): In this stage, learners begin to make sense of their reflections, forming abstract concepts, generalizations, or theories based on their observations. Medical students might connect their patient experiences to underlying medical principles, diagnostic frameworks, or treatment protocols. Lectures, readings, and theoretical discussions play a crucial role in this phase, helping students build a cognitive framework.

-

Active Experimentation (AE): The final stage of the cycle is active experimentation. Here, learners apply their newly formed concepts and theories to new situations. This is where they test what they have learned. In medical education, simulation exercises, planning treatment strategies, or even real clinical encounters under supervision provide opportunities for active experimentation.

The cycle is continuous and iterative, meaning that active experimentation leads to new concrete experiences, restarting the cycle at a higher level of understanding and skill. This continuous process of experiencing, reflecting, conceptualizing, and experimenting is what Kolb argues leads to deep and meaningful learning.

Adapted Kolb's experiential learning cycle illustrating the four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation.

Adapted Kolb's experiential learning cycle illustrating the four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation.

3. Application of Kolb’s Cycle in Medical Education: An Evidence-Based Approach

The principles of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle are particularly relevant to medical education, a field that inherently blends theoretical knowledge with practical skills. A study conducted at the Technical University of Munich provides a compelling example of how this cycle can be systematically applied in a medical curriculum to enhance student learning. This study focused on designing a course for medical students preparing to become general practitioners, explicitly structured around Kolb’s cycle and Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).

3.1. Course Design Based on Kolb’s Cycle

The course was designed to address common chief complaints encountered in general practice, aligning with EPAs relevant to family medicine clerkships. The course structure intentionally mirrored Kolb’s cycle:

-

Concrete Experience: Students began with real-world clinical experiences during their family medicine clerkships. They encountered actual patients and their diverse medical issues, providing the foundational concrete experiences.

-

Reflective Observation: The first seminar in the course was dedicated to reflective observation. Students discussed patient cases they had personally encountered during their clerkships. This sharing and discussion facilitated reflection on their experiences, allowing them to analyze different aspects of patient presentations, their own responses, and the clinical context.

-

Abstract Conceptualization: Following case discussions, the seminar shifted to abstract conceptualization. Teachers presented relevant medical theory, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies related to the discussed chief complaints and EPAs. This phase aimed to provide students with the theoretical frameworks and knowledge base to understand and interpret their clinical experiences. Skill-based training was also incorporated in this stage to build foundational competencies.

-

Active Experimentation: The second seminar focused on active experimentation through simulation. Students participated in scenarios with standardized patients, simulating cases similar to those they had seen in their clerkships and discussed in the first seminar. This allowed them to apply their newly acquired knowledge and skills in a safe, controlled environment, receiving immediate feedback from standardized patients, peers, and instructors.

3.2. Evidence of Effectiveness: Course Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of this Kolb-based course design, the researchers collected student feedback through evaluation forms. The results were overwhelmingly positive, providing evidence for the value of this approach.

-

Student Appreciation: Students rated both the seminars and the simulation training highly, with average grades indicating strong approval. They particularly valued the opportunity to discuss personally experienced patient cases and the chance to practice skills in a simulated setting.

-

Perceived Learning Goal Achievement: A significant majority of students felt that the course effectively helped them achieve the learning goals. This suggests that the structured integration of experience, reflection, theory, and practice was successful in facilitating learning.

-

Specific Components Highly Valued: Students specifically highlighted the value of discussing real-life patient cases for making clinical relevance clear and for introducing common chief complaints. They also appreciated the opportunity to repeat and refine clinical skills in the simulation sessions and valued the debriefing and feedback components of the simulation training.

These evaluation results offer direct evidence supporting the effectiveness of a course design grounded in Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle in medical education. The students’ positive feedback and perceived learning gains underscore the potential of this approach to enhance the learning experience and prepare them for clinical practice.

4. Broader Evidence Supporting Kolb’s Cycle

While the study at the Technical University of Munich provides specific evidence within a medical education context, broader research across various fields supports the effectiveness of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle. Studies in engineering education, laboratory training, and business education have shown that instructional designs based on Kolb’s cycle often lead to improved student engagement, deeper learning, and better retention of knowledge compared to more traditional, less integrated teaching methods.

Meta-analyses in education research also highlight the importance of active learning, reflection, and feedback – all core components of Kolb’s cycle – in promoting effective learning outcomes. The cycle’s emphasis on connecting theory to practice and providing opportunities for learners to actively apply their knowledge aligns with constructivist learning principles, which are widely recognized for their effectiveness in fostering meaningful learning.

Furthermore, the ALACT model, which emphasizes reflection in professional development, shares significant overlap with Kolb’s cycle, particularly in the stages of reflective observation and abstract conceptualization. This convergence across different educational models strengthens the theoretical foundation and practical applicability of experiential learning approaches like Kolb’s cycle.

5. Benefits and Considerations of Kolb’s Cycle in Medical Education

5.1. Benefits

- Enhanced Learning Integration: Kolb’s cycle provides a framework for intentionally linking different learning modalities – clinical experience, case discussions, simulation, and theoretical input – creating a more cohesive and integrated learning experience.

- Improved Clinical Reasoning: By systematically moving through the stages of the cycle, students are encouraged to develop stronger clinical reasoning skills, connecting observations to concepts and applying knowledge in practical scenarios.

- Increased Student Engagement: The active and experiential nature of the cycle can enhance student engagement and motivation, as learners are directly involved in the learning process and see the immediate relevance of their learning to real-world practice.

- Development of Reflective Practice: The emphasis on reflective observation encourages students to develop habits of reflective practice, a crucial skill for lifelong learning and professional development in medicine.

5.2. Considerations

- Resource Intensive: Implementing a Kolb-based curriculum, particularly with simulation components, can be resource-intensive, requiring dedicated faculty time, simulation facilities, and standardized patients.

- Context Specificity: While the principles of Kolb’s cycle are broadly applicable, the specific implementation needs to be carefully tailored to the context, learning objectives, and student population.

- Need for Skilled Facilitation: Effective facilitation is crucial for guiding students through each stage of the cycle, particularly in the reflective observation and abstract conceptualization phases. Instructors need to be skilled in facilitating discussions, providing constructive feedback, and connecting experiences to theoretical frameworks.

- Further Research: While initial evidence is promising, further research is needed to objectively measure the long-term learning outcomes and impact of Kolb-based medical education programs, including comparative studies and investigations into the transfer of learned skills to real clinical settings.

6. Conclusion

The evidence, including the study at the Technical University of Munich and broader research in education, suggests that designing medical education programs around Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle offers a valuable and effective approach. By intentionally integrating concrete experiences, reflective activities, theoretical learning, and active experimentation, medical educators can create more engaging, relevant, and impactful learning experiences for students. This approach not only enhances immediate learning outcomes but also fosters the development of essential skills such as clinical reasoning and reflective practice, ultimately better preparing future physicians for the complexities of healthcare. Further research and continued innovation in applying Kolb’s cycle will likely yield even greater benefits for medical education and, ultimately, patient care.

References

[1] Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Gordon DL, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10–28.

[2] Kneebone R, Kidd J. Simulation in surgical training: educational issues and practical implications. Med Educ. 2001;35(10):907–915.

[3] McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003-2009. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):50–63.

[4] Norman G. Dual processing and diagnostic errors. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2005;10(1):23–32.

[5] Torre DM, Daley BJ, Stark-Schweitzer T, et al. A comparison of think-aloud and clinical reasoning mapping exercises to teach clinical reasoning skills to medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):27–37.

[6] Lateef F. Simulation-based learning: just like the real thing. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(4):348–352.

[7] Brydges R, Dubrowski A, Regehr G. A framework for the use of simulation in procedural skills training. Acad Med. 2010;85(8):1340–1346.

[8] Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–e115.

[9] Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, Gick W, Holmboe E, Yadav A, et al. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Findings from a literature review. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):403–441.

[10] Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1517–1525.

[11] Ten Cate O, Chen HC, Hoff RG, Peters H, Bok V, van Sluisveld N, et al. Curriculum development for competency-based medical education: AMEE Guide No. 99. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):325–339.

[12] Englander R, Carraccio C, Aschenbrener CA, ten Cate O. From theory to practice: the case of entrustable professional activities in pediatrics. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):763–766.

[13] Hauer KE, Kohlwes J, Cornett P, Wimmers PF, Earnest MA, ten Cate O. Identifying entrustable professional activities in internal medicine to improve assessment and training decisions. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):822–829.

[14] টাইমস BD. Importance of Interlinking different educational formats. Times BD. 2023. Available from: https://timesbd.com/national/education/importance-of-interlinking-different-educational-formats

[15] Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

[16] Baker AC, Jensen PJ, Kolb DA. Conversational learning: An experiential approach to knowledge creation. Westport, CT: Quorum Books/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2000.

[17] Korthagen FAJ, Vasalos A. Levels in reflection: Core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teach Teach Educ. 2005;21(1):47–71.

[18] McCarthy P, McCarthy C. When case-based teaching is not enough: Integrating Kolb’s experiential learning cycle to improve student learning. Teach High Educ. 2006;11(4):461–473.

[19] Felder RM, Silverman LK. Learning and teaching styles in engineering education. Eng Educ. 1988;78(7):674–681.

[20] Hattie J. Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge; 2008.

[21] Bransford JD, Brown AL, Cocking RR, editors. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.